George W. Sutton Jr. was brought in to replace Florence M. Osborne. How did that happen?

George W. Sutton Jr. (really George W. Sutton III) was the scion of a Long Island family of considerable wealth and influence. His grandfather, George W. Sutton, was a silk trader and importer who bought a twenty acre estate in New Rochelle. This George had five sons; one, the real George W. Sutton Jr., was a local luminary in New Rochelle; member of the yacht club, tax commissioner, realty developer and president of the local telephone company in addition to working in his father’s business.

George Jr.’s son, George III (1887-1958), grew up among the rich and developed a love for boats and motor cars. He was editor of his college magazine; it was natural that he entered journalism. But not before he tried to do business in East Africa (now Tanzania); he was in the ivory and cloves export/import business there for two years.

As a journalist, he wrote articles on boating and yachting, a few stories including three for Adventure in the early teens, and rose to become editor of Motor Life (established 1906) sometime in or before 1915. A member of the National Guard, he served on the Mexican border in 1914 and later became a captain before joining the US Army in 1918 and being assigned to the tank corps. He was sent to France and there he was reassigned to the US Air Service, Information Section; his assignment was to help create a history of the Air Service in WW1. He returned to the U.S. and was discharged in March 1919. He again became editor of Motor Life and wrote on automotive subjects for other magazines including Vanity Fair, House and Garden, Yachting and Field and Stream in the 1920s.

Was he a good choice to edit Black Mask, an all-fiction magazine? Maybe. It didn’t hurt that his uncle, A. W. Sutton, was treasurer of Eltinge Warner’s company and President of Pro-Distributors, the company that published Black Mask. Eltinge Warner, if you recall, was the publisher of Field and Stream and now sole owner of Black Mask(H. L. Mencken and Jean Nathan had sold him their shares in early 1921.).

Sutton’s first issue (per the contents page) was the one of October 1922. Most stories in that issue were by authors who had already published during Osborne’s tenure, including Harold Ward, Herman Petersen, Jack Gottlieb, Robert Russell, Murray Leinster and Howard Rockey.

One new author was present would boost Black Mask’s circulation even more than Dashiell Hammett. Dolly, by John Carroll Daly, wasn’t hard-boiled and it didn’t feature Race Williams, his famous series character. Whether Sutton bought that story or inherited it in the inventory from Florence M. Osborne is unclear. However, other changes that he made during his tenure at Black Mask were clearly his idea.

First was a shift towards recurring series. October 1922 contained the first story in the Prentice series by James A Goldthwaite (1884-1967). Goldthwaite was a Harvard graduate who had become a high school mathematics teacher in Boston and wrote horror fiction in his off-hours under the pseudonym Francis James. He had published only one story earlier, in Detective Story Magazine.

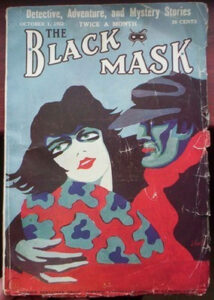

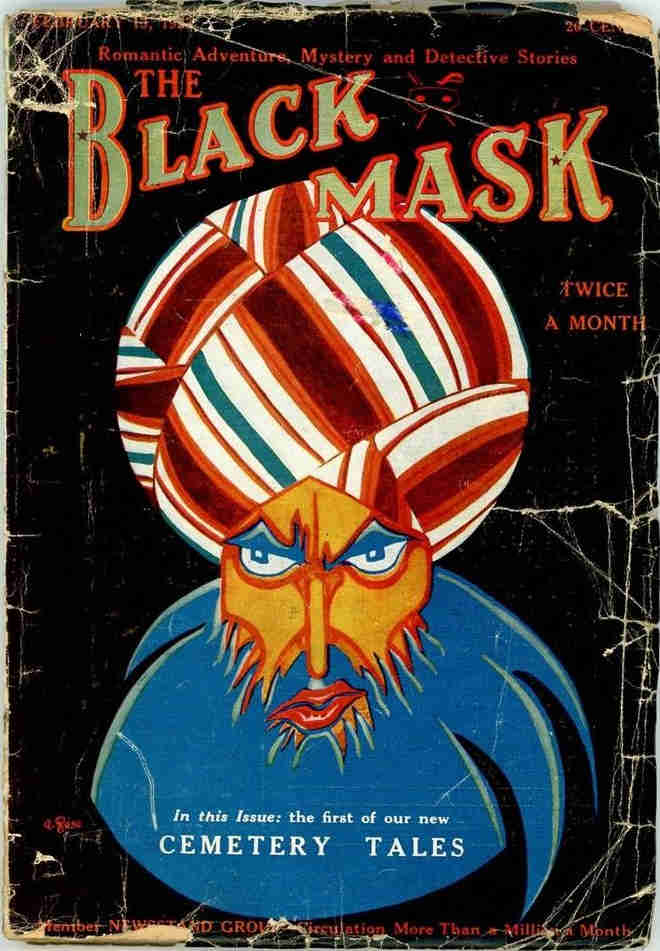

Other series Sutton introduced in quick succession were Ray Cummings’ T. McGuirk, Drayton Dunster’s Cemetery Tales, Eustace Hale Ball’s The Scarlet Fox and Charles Somerville’s The Manhunters. Noteworthy for their effect on circulation were Daly’s Race Williams stories, which started with the Jun 1, 1923 issue. Did I mention Sutton also published the first Continental Op story (Arson Plus) by Dashiell Hammet?

(Issue containing the Hammett story, Arson Plus)

Sutton also published the first serial in Black Mask. A Million a Year by Roy L. McCardell ran from November 1922 to February 1923. It was the subject of a minor controversy when the author entered it in a movie scenario contest run by a Chicago newspaper and failed to win even a consolation prize. He said that he had received a letter from a contest judge, claiming that the prizes were awarded not on merit but for maximum publicity, and that the first prize should have been awarded to McCardell’s story. The prize instead went to Winifred Kimball, whose story was made into Broken Chains (1922).

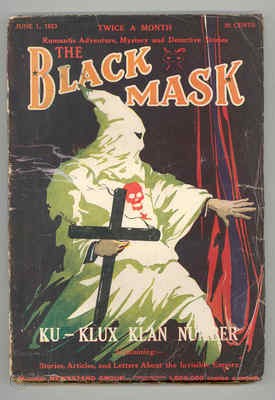

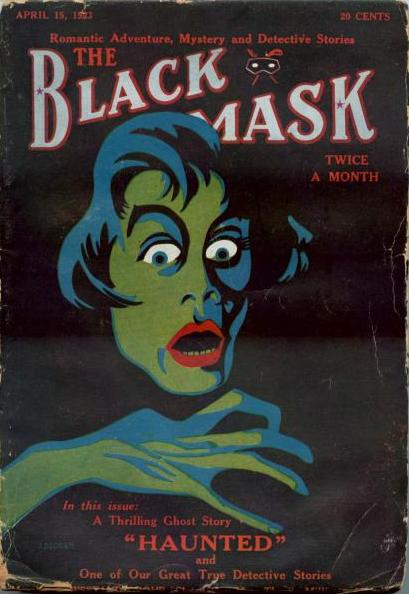

Sutton also published the first and perhaps last themed issue; June 1 1923 was the infamous issue focusing on the Ku Klux Klan, refusing to take an editorial stand on the Klan while allowing authors to provide competing viewpoints in their stories. Readers waded into the fray with their letters.

This issue is also notable for the first Race Williams story by John Carroll Daly. Williams was a very early hardboiled detective; he talked in Damon Runyon slang and lived under a perpetual cloud of gunsmoke. It’s a wonder he could see to shoot straight. Daly’s Race Williams stories were reader favorites and guaranteed circulation boosters; the series lasted more than eighty stories over thirty-two years and appeared in seven different magazines.

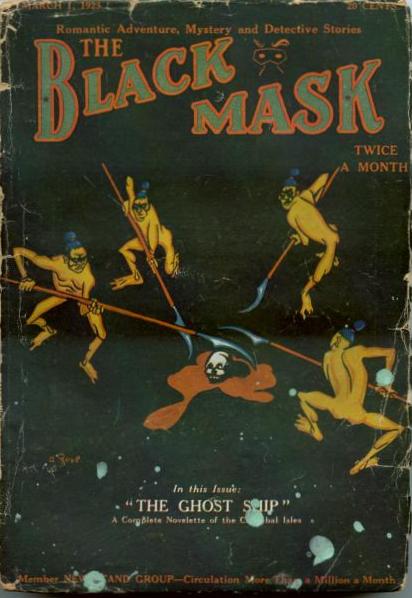

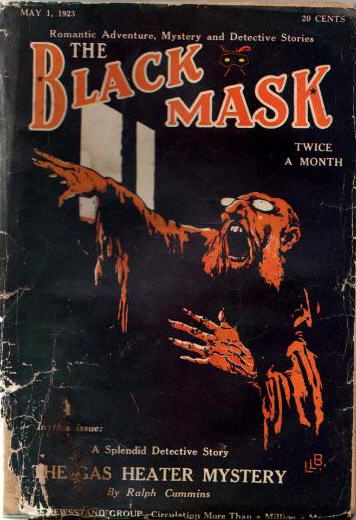

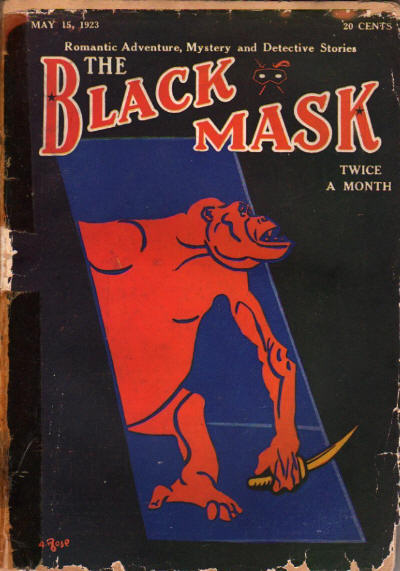

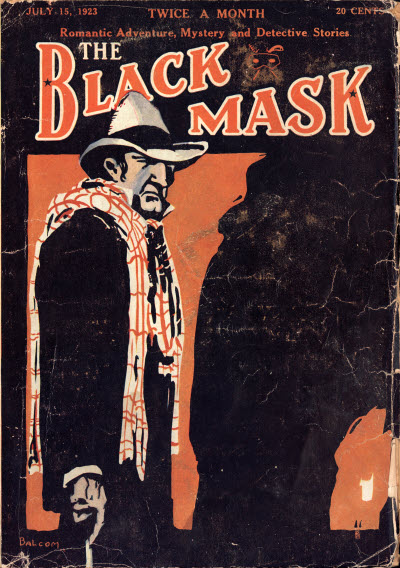

Other innovations attracted less controversy. Other pulps sported painted covers, Black Mask switched to striking poster like covers by various artists. These often contained a fantastic or horrific element, keeping in tune with the addition of horror to the contents.

With the February 1923 issue, the magazine’s frequency increased to twice a month. The editor’s workload doubled and his free time decreased. I’m pretty sure this was one of the reasons that Sutton was able to get an assistant editor. Harry Clark North(1896-1954) was chosen for the job; it was an interesting choice. Harry was the child of John H. and Caroline North. John was a prison officer at the Dannemora maximum security prison in New York; sometimes called Little Siberia for its cold winters and relative isolation.

Harry graduated from Brown University in 1920, having taken a break in the middle of his studies to join the ambulance corps in Italy during World War 1. After graduation, he worked in New York City as a salesman before joining Warner Publications, the owner of Black Mask, as associate editor. While most of his letters have vanished – some addressed to Erle Stanley Gardner and Hammett have survived. They reveal a man with firm opinions and a command of direct, colorful language. One rejecting a Gardner story said: “This stinks.”

Gardner had his own revenge some time later when he wrote a story he considered good: “If you have any comments on it, write them on the back of a check.” North bought the story and printed Gardner’s letter in the magazine.

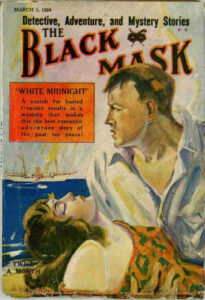

One change that Sutton introduced was a step in the wrong direction, or at least not one that most readers would associate with Black Mask. He added adventure stories with a romantic element into the magazine; notable among them was Marjorie Stoneman Douglas’ serial White Midnight (four instalments from March 1, 1924 to April 15, 1924).

Failed doctor turned ship’s cook, John Storm, is taking care of a leper on shore when the leper gives him a big gold ring, recites a few words that might be a clue to something and then expires dramatically. Storm is immediately pursued by a giant African American who tries to steal the ring. Jumping into the sea, Storm heads towards his ship only to find he has boarded the wrong vessel.

There a woman, claiming to be descended from Henry Morgan and currently self-employed as a bootlegger, tries to get the ring from him. She can’t find it because he has it in his mouth. And won’t talk. She sends him down to sleep. He wakes up, remembers the sequence of events (as if someone could forget them) and wonders why she wants the ring.

He goes up and finds her ready to set the giant on him again. He holds the ring and threatens to drop it in the sea unless she cancels the violence. She sends the giant away but manages to get close to him while murmuring sweet nothings in response to his questions. Then she bites him, grabs the ring and runs away. And that’s just the first two chapters. Douglas was paid six hundred dollars for the serial, it was her first big success and convinced her to take up writing full-time.

(From University of Miami)

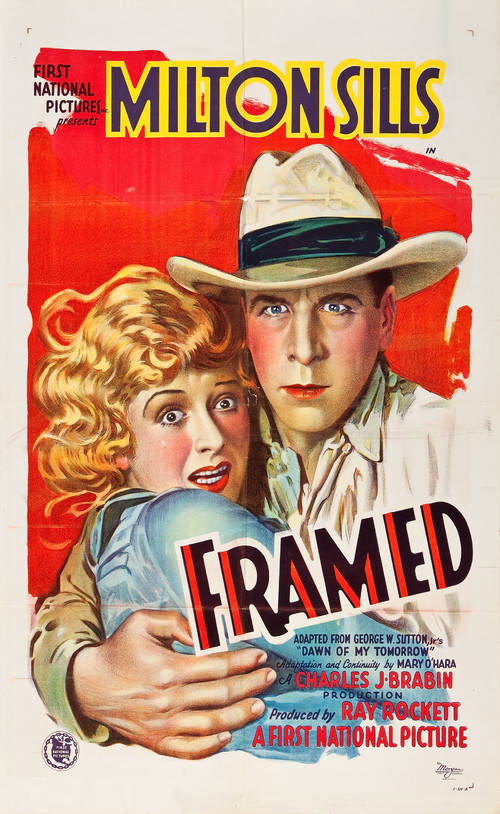

Sutton departed in March 1924. The last issue under his supervision had two stories and two letters from Hammett, whose value he recognized. Sutton went back to freelance writing, selling articles about motorboats and made occasional forays into screenwriting in Hollywood. His 1914 story, The Dawn of my Tomorrow, was filmed as Framed (1927) and another story, The Golden Mummy, was supposed to be produced by First National. Later Sutton would enter public relations; his editorial career was over.

Though Sutton was only editor for about a year and a half, he appears to have had more influence as editor. He encouraged Hammett, Gardner, and Daly to write for Black Mask and the KKK issue was one of the more interesting in the history of the pulps. The magazine is definitely more interesting than the earlier issues.