Last week, we saw Popular Publications was struggling to make money on Black Mask at the fifteen cent price point in 1946. How could they make it work? In May 1946, Black Mask went to publishing every other month, a sure sign of trouble. Detective Fiction Weekly had stopped publication in 1944. Dime Detective was still coming out monthly; it was transferred to Harry Widmer early in 1947. Ken White must have been scratching his head trying to figure out a new direction.

New Ideas

With the May 1947 issue, Popular relaunched the magazine. They added 32 pages; Black Mask was back to its pre-war size at 128 pages. The magazine was printed on a better grade of paper and the font size increased. There were 48 lines to a column; the number of words remained around the same as the earlier 96 page version. It looked better and read easier. It was still being printed by the Cuneo Press, Chicago.

Plots and crimes were a little more realistic, characterization was better and in general, there was a greater variety of backgrounds. Authors like John D. MacDonald, Bruno Fischer, Richard Deming, William Campbell Gault and Frederic Brown made their debuts. You couldn’t confuse it with Dime Detective anymore. Publication was still every other month.

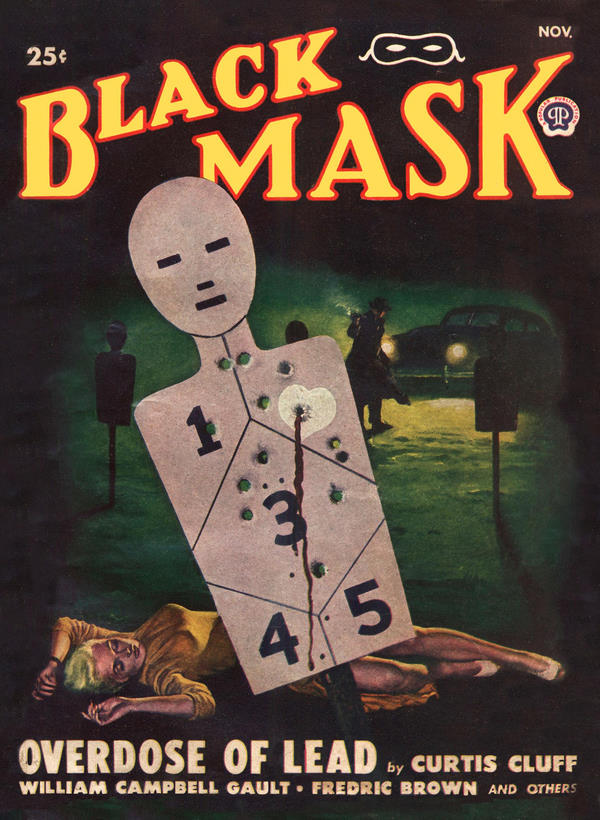

Could it work? Let’s look at the November 1948 issue and find out.

The art

The cover by Peter Stevens conforms to the new theme: means of death in the front, a crime scene in the background. A bullet-riddled human shaped target bleeding from the heart in the forefront; a dead woman in a golden dress lying down while a man in a trenchcoat and fedora stands further away from her, smoke rising from the gun in his hand. Interior illustrations weren’t credited but were all in the same style; they could be by Stevens.

The Stories and their authors

Elton Curtis Cluff (1914-1963) was born in Norfolk, Virginia, and grew up there, studying at the University of Virginia. After naval service in World War 2, he went to Hollywood to write TV and movie scripts. During that time, he also wrote four stories for Black Mask. Then he became an advertising executive and worked for various Hawaiian airlines to promote tourism. During that stint, he also helped shoot various episodes of TV serials in Hawaii.

Overdose of Lead stars Chuck Conrad, a graduate of the Race Williams’ Detective School. He carries a gun and recently captured a cop killing bank robber. This brings him to the attention of torch singer Jeanne Barre, who has just found out that a mob boss owns her contract, in writing. She’s headed for big things in Hollywood, if only she can come out of his clutches. The boss is murderous and has a hair trigger temper. Barre asks Conrad to get the contract back. No one tells the whole truth, including Jean; Conrad gets his lumps and serves justice, even if he has to break the law. If that reminds you of a certain detective who debuted the same year as this issue, you’d be…right. The story was filmed in 1958 as an episode of Mike Hammer. You can watch it on Youtube. Readable.

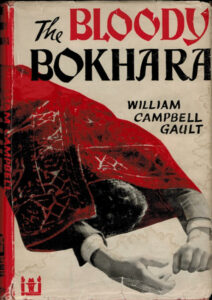

The Bloody Bokhara by William Campbell Gault is Gault’s take on Hammett’s Maltese Falcon. It has the same ingredients, the detective who can empathize with a criminal mind, the glamorous temptress, the valuable McGuffin and the scheming criminal mastermind who’s after the McGuffin.

But this is Gault, not Hammett, at work. The detective is the son of an Armenian immigrant carpet dealer who’s caught between his family’s culture and values and American culture. Gault’s sensitivity to social issues is visible. He doesn’t offer the usual simplistic pulp resolution; showing us the darkness in men’s hearts. But there is a tiny glimmer of hope at the end.

Gault later expanded this into one of his non-series novels, published by E. P. Dutton in paperback format in 1953. Very good.

Californian Wilbur Coleman Meyer’s(1902/3-1996) Gun in His Back is short and sweet. Just the thing to pick you up after the previous two stories, with a nice kick in the very last line. Good. Coleman Meyer was a race car driver and airplane pilot who became a salesman and wrote about thirty stories from 1945 to 1950.

Tom Marvin is likely a pseudonym of a pro writer. Harm’s Way is a nice police procedural, only the police aren’t really interested in finding out who the killer was, they think the husband did it. The wife isn’t dead, yet, but she’s lying in hospital with a bullet in her head and needs brain surgery. The husband needs money to give her the best medical care and determines to find out who shot her, possibly by accident, and get the money from them. A good motive for him as he goes around digging up the truth, quite literally in this case. Good.

Odds on Death by Don M. Manciewicz is a gambling story, something that would have been rejected by Joe Shaw. It’s narrated by a barman, who’s telling a story of his past to a customer. Not only is our hero a gambler, he’s a continuous loser, to the point where the gambling den boss comes to think of the gambler’s salary as his rightful due. WW2 happens and the gambler goes out, and comes back, changed by the war. He has a new dignity and stands up for himself as he proceeds to gamble for high stakes with the roll he’s managed to accumulate during the war. What happens next depends on a full understanding of the dice game craps, which I don’t have, causing me to thrill a little less. But the climax redeemed it a little. Readable.

Cry Silence by Fredric Brown is a little gem. I’m sure you’ve heard this philosophical conundrum: If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? Fred Brown wrote this story around that. It’s short, so no spoilers from me. Just read it in The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask stories.

Dead Men Can’t Welsh by Mel Colton aka Californian Hal Braham(1911-1994) is up next. A senator’s wife falls to her death from a window in his apartment building; the senator faces re-election soon and would be vulnerable to a scandal. The death is quickly ruled an accident by the police and the prosecutor; but the PI who was asked to investigate by the senator has doubts. The police chief doesn’t want the case reopened. Not that the PI is going to listen. The temptations of power and privilege and their results are clearly visible here. Good with a little twist in the ending.

Did the new formula work?

The stories offer a variety of settings, a range of professional and amateur detectives and sub-genres of the detective/crime/mystery story. The stories are good, the artwork professional and the magazine layout well-designed. It’s pretty much the same package as Manhunt, the detective story magazine that launched the crime digest revolution in 1952, selling over 600,000 copies with its very first issue.

But it didn’t work. Sometimes you have the right product at the wrong time. Science fiction magazines had moved to digest format and retained their readers, but overall pulp readership was declining.

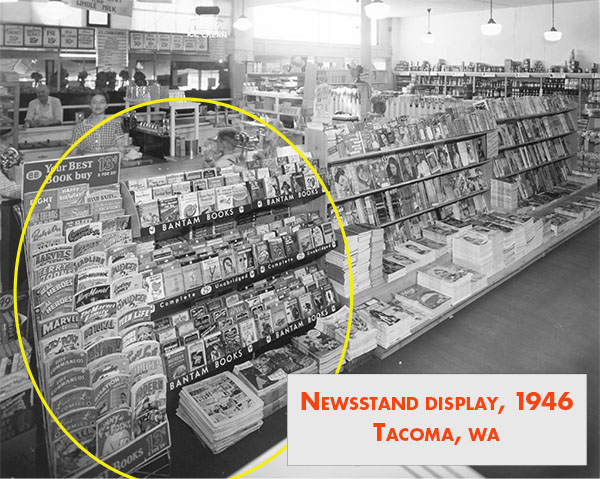

Contrary to some, I don’t believe that either radio or TV had a lot to do with the decline of pulps. Instead, I blame cutthroat competition for the reader’s dollar. Post war removal of paper supply restrictions meant that many new publishers put out comics and paperbacks. Comics were attracting younger readers while paperbacks lured older readers with low prices and a convenient format. There was a glut of reading material on newsstands in the late 1940s. No matter how good its content was, the pulp magazine was on its way out. Slicks, digests and paperbacks would dominate the next three/four decades.

in this photo of a newsstand in Tacoma, Washington c. 1946

This was the next-to-last issue edited by White. He left Popular Publications to work at Esquire, then became a book agent before his untimely death in 1964. With the next issue, Harry Widmer took over as editor.

Next week: The ace editor

I think economics played a big part in the death of the pulps. It simply was a lot cheaper to produce a far smaller digest format magazine and the even smaller and cheaper paperback format. The smaller formats made distribution easier also.

Also, I would give more influence to TV programs. Not so much in the late 1940’s but by the early and mid-fifties many pulp readers would spend the evening watching westerns and detective dramas.

I agree about the lower cost smaller format driving the pulps out. The digest boom in the fifties is evidence enough for that. But the timing had to be right, we’ll see more about that next week.

TV, though? By the early 1950s, most pulps had died. The remaining lingered on their way to a slow death by 1955 or so.