The question of whether to reprint old stories or not was always a thorny one for pulp publishers. While many know about the so called “reprint menace” of the 1930s and 1940s when publishers like Harry Donenfeld and Martin Goodman pushed out pulps full of reprints without identifying them as such, few know of an earlier such incident.

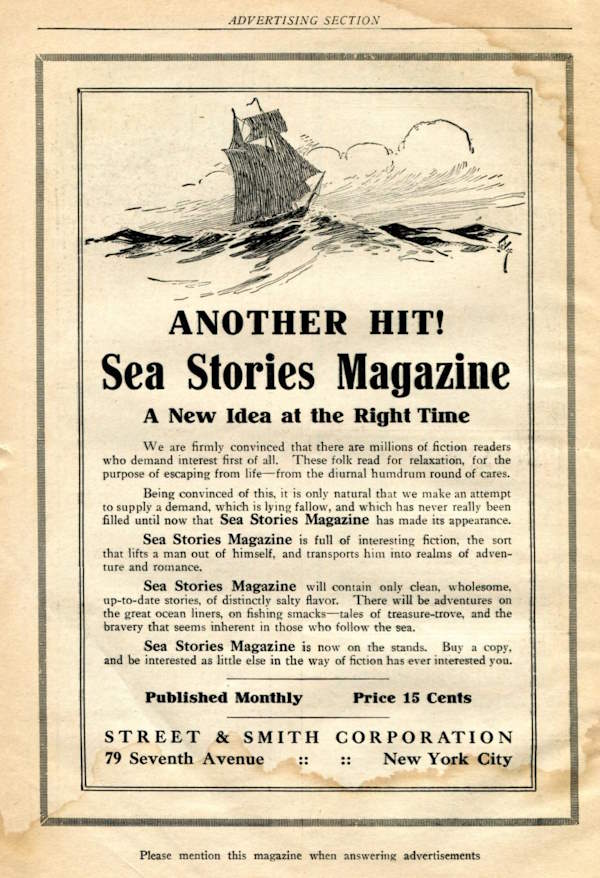

Sea Stories Magazine, 79 Seventh Avenue, New York, is a new publication added to the group published by the Street & Smith Corporation. The first number was issued December 14th.

That is the announcement for the launch of Street & Smith’s new magazine in The Student Writer, January 1922. The new magazine, unusually, was not advertised in newspapers; only in S&S’ own magazines (the image below being a sample).

The announcement in The Student Writer continues

A letter from H. W. Ralston of the corporation states:

“We are going to confine Sea Stories Magazine to the publication of rattling good stories of the sea. No second-rate material will be considered. We do not insist that the authors whose work appears in Sea Stories Magazine be well-known, but we do insist upon their material being clean and full of action.”

It is understood that the rates paid for material will approximate those paid by the other magazines in the Street & Smith group. This means usually better than one cent a word.

Noble goals indeed, but how did they work out in practice? The announcement above appeared in the January 1922 issue of The Student Writer, an author’s trade magazine. S&S had already put out the first issue of Sea Stories Magazine, dated February 1922. Were authors going back in time and responding to the call to action?

This is the table of contents for the first issue, taken from the FictionMags Index.

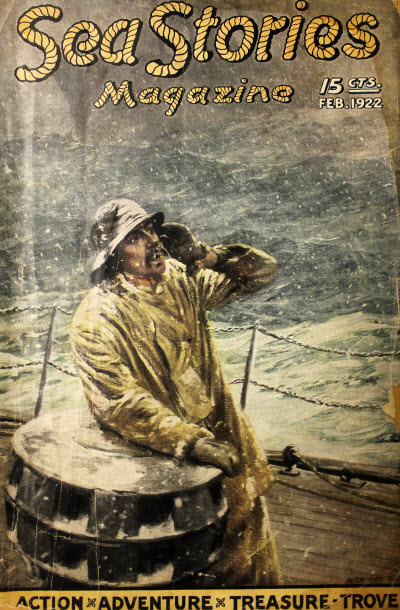

Sea Stories Magazine [Volume 1 Number 1, February 1922] (Street & Smith Corporation, 15¢, 144pp+, pulp, cover by Anton Otto Fischer)

Details supplied by Richard Fidczuk from Table of Contents

5 · Hidden Money · Henry C. Rowland · na

49 · Outward · [uncredited] · pm

50 · Beast Number 106 · Albert Dorrington · ss The Popular Magazine November 15 1909

58 · Lochinvar of the Lakes · J. Oliver Curwood · ss People’s November 1907

69 · The End of the Drag Rope · T. Jenkins Hains · ss The Popular Magazine February 1907

76 · The Devil’s Pulpit [Part 1 of 7] · H. B. Marriott-Watson · n. The Popular Magazine July 1907

97 · The Mate’s Romance · A. M. Chisholm · ss The Popular Magazine December 1907

107 · Peter Pringle’s Parrot · Wallace Irwin · pm Smith’s Magazine May 1914

109 · Will o’ the Wisp · George Allan England · nv People’s Ideal Fiction Magazine November 1911

138 · Bunkered · Edgar Beecher Bronson · ss The Popular Magazine December 15 1909

143 · Sea Curios · [uncredited] · cl

Let’s take a quick glance at the first issue. 7 short stories, 1 serial instalment and two poems, 144 pages in all for 15 cents. Not bad value for money, it appears.

A second glance gives the game away. All the contents are reprints, except perhaps one of the poems. The only new things are the cover illustration and the interiors (which had to be done because the original printings didn’t have any accompanying illustrations). Even there S&S cheaped out and copied the illustrations for one of the poems, Peter Pringle’s Parrot, which had been originally published in Ainslee’s.

Of course, there’s no indication of this in the table of contents. Which provoked reaction from authors, irate at seeing their stories reprinted without their permission and presumably without any payment. It took some time for the reaction to reach print, though. In the June 1922 issue of The Student Writer:

MR. Perriton Maxwell, editor at various times of The Metropolitan, Nash’s Magazine, Judge, Leslie’s Weekly, and Arts and Decorations, writes in vigorous protest against the republication by Street and Smith in the May Sea Stories Magazine of one of his short stories which was first published in The Popular Magazine (belonging to the Street and Smith group) back in 1908. It appears that this second printing was made without his permission and without any notice to the readers that the story had previously been published. Moreover, the editor of Sea Stories refused a request from Mr. Maxwell for additional compensation.

Of course, Mr. Maxwell has no legal standing whatever in protesting against this act of the publishers’ since he admits that he signed away “all rights” when he endorsed his original check. Most writers will agree, however, that he has a justifiable complaint on moral grounds. He says that this eighteen year-old story, “Mishaps Amain,” is “an exceedingly poor thing” written early in his career. Isn’t it a bit tough on Mr. Maxwell to publish it without explanation, leaving the reader to believe that it represents the author’s present ability as a fiction writer?

Moreover, if this is not an isolated case, but the beginning of a settled policy, should not the publishers announce the policy so that writers may have some basis for gauging the size of the market for original stories offered by the Street and Smith group? Sea Stories is probably not going to become a Golden Book or a Famous Stories Magazine, but how far is it going in that direction? Mr. Maxwell ends his letter, “I would like to know what some of the seasoned old war horses think of this sort of thing.”

To which other authors responded in the September 1922 issue of the Student Writer:

IN June Mr. Perriton Maxwell, present and erstwhile editor of many well-known magazines, protested vigorously in these pages against the republication by Street & Smith in their Sea Stories magazine of one of his stories, which had been published years before in another magazine controlled by this corporation. He resented, and rightly, the fact that no explanation was made that this story was one of his early literary endeavors and far below his present standard of accomplishment. But since they owned the copyright, which he had innocently surrendered, they were within their legal rights in republishing, and he had no redress against what he considered an affront to his present-day reputation as a writer.

Comes a letter from Captain Dingle, writer to the millions of fascinating stories of the sea. He says in part:

“A friend showed me a copy of The Writer containing the series of letters on Author’s Doubles, because my own was there. In reading through the magazine — a good one — I saw Perriton Maxwell’s case against Sea Stories presented: or his grievance, since he of course has no case.

“The only surprising thing about that is that it seems worthy of comment. Has not that method been Street & Smith’s ever since they started Sea Stories? I know they have reprinted some two dozen old stories of mine from their other magazines, without credit or a word to say they were old reprints, and these old yarns appeared as new stuff while my real new stuff was running in the Post, Collier’s, and other publications.

“They also reprinted the work of dead men. … Morgan Robertson (d. 1915, reprinted Jul 1922), Clarence L. Cullen (d. Jun 1922, reprinted September 1922), and I believe John Fleming Wilson (d. Mar 1922, reprinted multiple times but only in 1923, so I don’t know why Dingle included him) and T. Jenkins Haines (not deceased, but not being published under his own name since 1911, reprinted in Feb, Apr and May 1922) all were dug up to stand watch. Mr. Maxwell is lucky to have had only one poor old story misrepresent him. I had over two dozen. And I never sold Sea Stories a story in my life. I sold them one bit of verse, but that’s all. Every story of mine they printed in Sea Stories was previously printed in People’s, Top-Notch, or All-Around in my first years of fiction writing.

“They are old and shameless offenders against the decencies of the profession, yet keep within the strict bounds of sheer LAW.”

The weird thing is that no Dingle items (poems, stories or articles) were reprinted in Sea Stories till the November 1922 issue, so what was Dingle complaining about here on his own behalf?

The article continues

There is little to be added to this letter except that a protest has been received and filed with public opinion against a practice which is not to be admired, even though sanctioned by law. Street & Smith should have known better than to try that on so doughty a crew as the seamen.

“Admirals of old days

Bring us back the bold ways;

Sons of all the sea dogs

Lead the line today …”

Who had this idea? Normally one would blame the editor, but the editor remains nameless in the early issues, and even the trade magazines don’t mention the name. Except…the July 1922 issue of Writer’s Digest lists H. W. Ralston as the editor of Sea Stories. Now things become a little clearer. Ralston, the man who would later come up with the idea for S&S’ line of hero pulps, was testing the waters. And he was doing it on the cheap by running reprints. The magazine probably made money for S&S from the first issue; though unfortunately we don’t have any circulation numbers for the magazine individually.

The next 3 issues (March, April and May) were all reprints too. A solitary original story appeared in the June 1922 issue, and by the October 5, 1922 issue had no reprints. But they hadn’t disappeared: Till September 1926, most issues carried reprints, and usually about a fourth of the content was reprints. Were reprints a way to balance the books, get suitable content or both? What do you think?

From October 1926, reprints disappeared; the content was all original. Except for very occasional reprints from The Corner or The Story-Teller, British fiction magazines. And so it continued till June 1930, when the last issue of Sea Stories was published.

The reprint question would crop up again in the late 1930s. The April 1939 issue of Author & Journalist (the new name of The Student Writer), carried this broadside

To authors who sell reprint pulp fiction to our competitors, Street & Smith remains a closed market.

Who said this? None other than our friend H. W. Ralston, the business manager, and Allen Grammar, the then President of S&S. And on that edifying note, this article ends. A review of the first issue of Sea Stories will follow soon.

Very interesting information here, thanks for sharing.

What a fantastic, scholarly and immensely interesting article. Thank you so much for taking the time to share your incredible research.