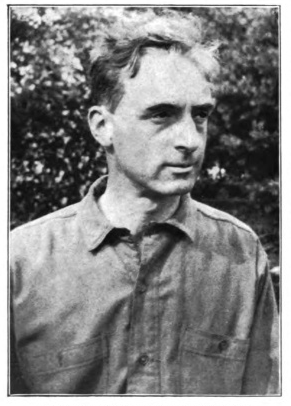

He was born on 28 September 1876, the son of Judge Ripley C. Hoffman and Mary Eliza Sullivant, in Columbus, Ohio. He was the only child of his father’s second marriage.

He attended school in Columbus, graduating from the Columbus high school and went on to get his BA from Ohio State University in 1897. His first job was as an English and literature teacher in the Coshocton high school, where he taught till 1899. He seems to have had some adventures of his own on a bicycle trip through France and Spain at this time.

In September 1899, in partnership with Walter Collins O’Kane, his classmate from school and college, he bought the Buckeye newspaper, published in Troy, Ohio. He was the joint editor and manager, and remained with the paper for the next 3 years. During this time, his father passed away, on 14 April 1900.

He seems to have a 2 year itch, changing jobs every couple of years after this. He became assistant editor at the literary magazine, The Chautuaquan (1902-03) and the Smart Set, (1903-04). Next, he joined Watson’s magazine (1904-1906), a controversial muckraking magazine run by Thomas Watson, where he became a managing editor after starting out as an assistant editor.

While working at Watson’s magazine he got married to Mary Denver James, a Bryn Mawr graduate, linguist and author on 14 October 1905. They might have met at meetings of the Ohio Mycological Society, of which both were members. His mother passed away earlier the same year, on 17 March 1905.

The last of these 2 year stints was at the Transatlantic Tales magazine, which published translated fiction, in 1907. This is where he met Sinclair Lewis, who worked there translating stories.

These editorships are well known; not so well known is that he was an author, producing a series of Irish stories about a Irish crook called Patsy Moran, and other stories that appeared in newspapers. He wrote at least five of the Patsy Moran stories for McClure’s and Everybody’s magazine:

- Patsy Moran and the lunatic. McClure’s August 1905

- Patsy Moran and the orange paint. Everybody’s, July 1907

- Patsy Moran and the warnings. McClure’s, July 1907

- Patsy Moran and the trappings of chivalry. Everybody’s, July 1908

- Patsy Moran, the book and its covers. McClure’s. August 1908

These jobs put him in the right place at the right time, and the right place was the job of the assistant editor of The Delineator, a woman’s magazine run by the Ridgway Company, and the right time was 1908, when he started this job. Professional success was accompanied by personal tragedy. His wife passed away five days after the birth of a boy, Lyne Starling, on 12 August 1910.

In 1909, the Ridgway Company was acquired by the Butterick Company, a magazine company that had originally begun by selling magazines with sewing designs for women and had gone on to become a standalone publishing business. The Ridgway Company was bought out for one million dollars (worth about 30 million dollars in today’s money).

The Butterick Company wanted to start a new magazine of outdoor action called Adventure, aimed at both men and women. Trumbull White, a noted explorer, was the first editor of Adventure, and it seems that Arthur S. Hoffman used to assist him. This may have been an official arrangement, or just the routine help around the office. What is clear is that the first time Hoffman was listed in Adventure as being on the magazine’s staff is in the issue of November 1911, and he was listed as managing editor in the issue of February 1912.

Hoffman had a clear editorial policy for Adventure, and he wasn’t shy in voicing his opinions on what he wanted:

Uses short stories of any length, but those under 3000 words preferred. Wants clean stories of action, well told for discriminating readers. Uses serials up to 90000 words, and novelettes up to 60,000 words; also some verse, sixteen lines or under, and some prose fillers of 250 to 650 words in keeping with the general character of the magazine. Adventure‘s preferences are stated to be: “First of all, clearness and simplicity; convincingness, or truth to life and human nature; well-drawn characters; careful workmanship. We want stories of action laid any place and any time—except in the future. We strongly prefer outdoor stories, and are glad to get stories of foreign lands. All stories must be clean and wholesome in expression, content and intent, but we want no preaching or moralizing. We accept stories either with or without the love-element; with or without women characters, but no stories in which the love-element is of more than secondary interest. We want no ‘fluffy,’ society, boudoir stories. We avoid psychological sex problem, sophisticated, supernatural and improbable stories; also stories of smuggling; mixed-color marriages; society atmosphere, or generally, millionaire circles; prisons; slums; newspaper offices and reporters; doubles; lost wills; memory lost or restored by injuries, etc.; lunatics; the moonshiner’s daughter who loves a revenue officer; college; and marvelous inventions. We have little interest in baseball, football, golf, racing, tennis, track athletics, etc.”

Mr. Hoffman adds an earnest appeal to the women writers. “Why,” he says, “do so many of you send us manuscripts that are as unsuited to Adventure as a tough prize-fight story is to the Churchman ? Thy send us a fluffy story opening with a boudoir talk between Mabel and Lucille about their silly, sugary love-affairs, or Stories of dull domestic or butterfly society life ?“ Or what he didn’t want:

“Most of the stories we turn down are lacking in character work. The author gives his folks names—‘John Jones’ or ‘Mary Smith’ without any other attempt to make them stand out. Somebody said the assigning of only one trait to a character would fix him’ in the reader’s mind. Well, that’s pretty elemental, but it’s better than nothing.”

“We also find in many of the manuscripts submitted a lack of relative proportion in plots. A tremendous temptation beckons the amateur writer who is telling the story of something that actually happened to enlarge on one interesting thing far beyond its merits. Because it was important at the time, it is more vivid in the writer’s mind than big incidents in the plot development, and he goes to pieces on that. Besides this, a man who has actually experienced adventure is often unable to know what incidents really were thrilling. He lacks the sense of dramatic values. A fellow dropped into the office the other day — began to tell me about killing an elephant. I didn’t care how they killed elephants. Quite nonchalantly he mentioned that there had been room on the tree concealing his servant and himself for only one man, so his little black servant boy had swung off to the ground. Then he went right on with his story—never even noticed the dramatic value of that incident. An elephant was more important to him than a little black boy, and he didn’t have the imagination to see that possibly others wouldn’t see the thing in the same light.”

“Though Adventure occasionally uses newspaper stories, we are against them as a genus. The stories of this type are usually pretty old ones to the reader and he is bewildered by technicalities and local color. Very often the writer is too young to write about anything—particularly when he hasn’t grasped his environment yet. Worst of all the usual plot of this type is the attempted and tiresome air of very youthful cynicism so blatantly handed out to the long-suffering readers in a majority of these tales.”

“Why do editors reject Mss?” Because 90% of them are so damned bad. Also because no magazine has room for many stories. Adventure,for example, appearing 24 times a year, prints about 250 short and long stories; it receives about 5,000. That is only 5%; magazines publishing fewer stories per year will average closer to 2%.”

I think that in setting these guidelines, Hoffman was influenced by his background and training. As an English literature graduate, he valued simplicity, clarity and good plotting. From his days at Watson’s magazine, he valued contrary opinions, and wasn’t afraid to voice them.

In his book, “Fundamentals of Fiction Writing”, he acknowledged various influences on his editorial policies, ranging from his college courses, where he learned that:

- The range of variation in imaginative responses among readers is huge.

- Readers find enjoyment in fiction because they are vicariously living the experiences of the hero.

He also acknowledged Tolstoy’s “What is Art?” as guiding him to emphasize simplicity. However, I think the popular features in Adventure – “Campfire” (Letters from readers and introductions, other letters from authors), “Wanted—Men and Adventurers” (For Hire and Wanted ads for Adventurers), “Ask Adventure” (Ask an expert) and “Lost Trails” (Find people with whom you had lost touch) – were his own ideas. He had this to say about starting Campfire:

“Gradually it grew on me that here was something more than a fiction magazine … Here was a certain community of interest. Among people who had hitherto had had no common meeting-place, no means of communication among themselves. Why not make that magazine that had collected them their meeting place?. . . Our ‘Camp- Fire’ represents human companionship and fellowship.”

This connection with the readers, and Hoffman’s editorial voice were what made Adventure different from the other pulps. That, and the constraint of starting out with a small budget for payments to authors, which made him seek out new authors who could work with him to get what he wanted. He succeeded at this, discovering and growing a stable of excellent authors including Talbot Mundy, Harold Lamb, Arthur O. Friel, Gordon Young, Hugh Pendexter, L. Patrick Greene, W.C. Tuttle, Georges Surdez, Albert Wetjen, Capt. A.E. Dingle and many others.

Adventure was a success under Hoffman, the circulation reached its peak of ~300,000. Argosy and The Popular Magazine were the only magazines with a higher circulation at the time. The number of issues went from once a month to twice a month and at its peak, it was being published thrice a month.

As if that wasn’t enough work to take on, Hoffman also played a part in setting up the American Legion before the first World War. On March 5, 1915, the American Legion was incorporated in New York. The stated objective of the organization was to organize American citizens to serve the country in time of war. The incorporation papers bore the names of Alexander M. White, Julien T. Davies, Jr., Arthur S. Hoffman, E. Ormonde Power and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

The tale of the origin of the American Legion was told by Dr. J. E. Hausmann, a former army officer: “A young American named E. D. Cook, who had left the United States presumably to join one of the European armies had providentially mailed a letter to the magazine editor of Adventure before sailing and in it had proposed a legion of adventurers to serve the country in warfare. The editor, Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, laid the plans before General Wood. The latter had approved of them, said Hausmann, as a valuable movement in the direction of preparedness. Hausmann pointed out that there were exactly eighteen men in the National Reserve. He said nothing of Cook’s fate.”

Around this time, he married again, on August 5, 1915 to Mary Emily Curtis of Syracuse, New York.

Hoffman wasn’t leaving anything to chance in the coming war; he got kids involved as well. In 1916, he helped set up the National School Camp Association to provide a supplementary means of defense by training boys from the age of 12 to 18, when they could enroll in the army.

Things went steadily well for Hoffman and Adventure till 1926. In that year , the owner of the Butterick Company, George Warren Wilder, decided to retire and sold a controlling stake to S. R. Latshaw and Joseph A. Moore. Latshaw had been the advertising director of the Butterick Company from 1915. Moore had been the treasurer of Good Housekeeping, Harper’s Bazaar, and other publications belonging to William Randolph Hearst. With new ownership came new management and directions. The Butterick Company took over management control of Ridgway, and decided to make Adventure into a “slick” magazine like Harper’s or Scribner’s.

For the next year, Hoffman watched the magazine he had grown turn into something he didn’t like, and saw its circulation drop by a fifth. He decided to leave Adventure, a decision which he announced in the Campfire of June 15, 1927.

“To have been with Adventure ever since it was born in 1910, nearly nineteen years ago, and at last to say good-by makes something of an occasion, at least as far as I am concerned. While I go of my own will, it is not possible to sever without a very real regret my relations not only with the magazine itself but with all of you who gather at Camp-Fire. We have met and talked together through the years, been friends, and saying good-by is not easy for me. So little easy that I shall say it briefly and have done.”

He became the editor of McClure’s in June 1927, and stayed there for nearly a year. In April, 1928, Hearst sold the magazine to James R. Quirk, publisher of Photoplay and Opportunity. Hoffman left the job subsequently, and went back to teaching. He became a teacher of fiction writing, authoring several books

- · The writing of fiction (1934)

- · The Service Offered in the Teaching of Fiction Writing (1939)

- · Fiction writing self-taught: a new approach (1939)

in addition to the books he had written earlier:

- · Fundamentals of Fiction Writing (1922)

- · Fiction writers on fiction writing (1923)

| Article title | Author | Journal | Date | |

| Magazines in the twentieth century | Theodore Bernard Peterson | 1956 | ||

| The Magazine maker | Vol 3-4 | August 1912-July 1913 | ||

| The Editor’s attitude towards the young author | Arthur S. Hoffman | The Best college short stories 1917-1918 | ||

| Training the younger boys | American Defense | Vol 1 no 1-9 | Jan-Oct 1916 | |

| The stories editors buy and why, compiled by Jean Wick | Jean Wick | |||

| Where and how to sell manuscripts; a directory | William Bloss McCourtie | The Writer | Vol 27 | 1915 |

| Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, ‘97 | Ohio State University monthly | Vol 6 | July 1914-June 1915 | |

| The standard index of short stories, 1900-1914 | Francis James Hannigan | |||

| Who’s Who in America, 1920 | ||||

| Members of the Ohio Mycological Club – Fourth list | Ohio mycological bulletin | 1903 | ||

| Sketches of 21 Magazines: 1905-1930, Volume 2 | Frank Luther Mott | |||

| As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Pre-History of Virtual Reality | Michael T. Saler | |||

| 1917 | The writer | Vol 29 | 1917 | |

| Letter from George Warren Wilder to Theodore Dreiser | Apr 26, 1926 | |||

| Delineator and Designer to be merged in the fall | Watertown Daily Times | June 17, 1926 | ||

| Arthur Sullivant Hoffman dies in Pennsylvania | The Putnam County Courier | March 17, 1966 |

In my opinion ADVENTURE was one of the very best fiction magazines, especially during the period of around 1918-1927, during the time Arthur Sullivant Hoffman was editor. The magazine impressed me so much that I compiled a complete set of the 753 pulp issues.

What are my qualifications for claiming the above? For the last 50 or so years, I've been reading and collecting just about every major magazine of note. Extensive runs of pulps, slicks, digests, literary magazines. ADVENTURE was a quality fiction market which we will never see again since fiction magazines are now down to about 5 digests: ANALOG, ASIMOV'S SF, F&SF, EQMM, and AHMM. I guess we should mention WEIRD TALES also.

You do mention one thing that I disagree with. It is true that ADVENTURE tried to turn into a higher quality magazine around 1926-1927, using better quality paper, distinguished and sedate covers, and Rockwell Kent illustrations. But Hoffman was supportive of this attempt. For many years in the Campfire he had mentioned that many readers did not give ADVENTURE a chance because of the pulp paper and action covers. He said these readers thought it was just another pulp, etc.

The attempt to raise quality and gain a higher circulation failed and may have led to Hoffman leaving the magazine. He really felt that the magazine deserved a better readership in line with the better paper, illustrations, and covers.

This is an excellent site and I encourage you to continue with posts like the recent ones on Friel, Pendexter, and Hoffman.

Hi Walker,

Appreciate your comments on the blog. I agree that the failure of the attempt to get a wider readership was probably the catalyst for Hoffman's leaving Adventure.

In the absence of more information, we'll have to leave the question of whether he supported the change to be decided if/when we get more data. What strikes me as curious is that he could have done this a long time ago (he seemed to have complete editorial control of the magazine), and that the management changes happened at the same time.

I'm not sure what changes happened to the other magazines in the Butterick company's stable at about the same time. That may be the smoking gun that settles the issue.

Anyway, thank you for the kind words on the blog. I plan a couple of future posts on authors who didn't write for Adventure – William Hazlett Upson (Alexander Botts in the Saturday Evening Post) and Paul Hosmer (Short Stories, Top-Notch).

Then i'll get back to another couple of Adventure authors – Robert and Kathrene Pinkerton; Farnham Bishop & Gilchrist Brodeur.

BOLETIN DE SILOS (Monasterio de Santo Domingo Silos (Burgos) España

Julio de 1904 – Rev. Nº 9 – pag. 407

Huéspedes

Entre los visitantes citaremos a tres jóvenes americanos M. Laurence S. Williams y su hermano M. Ellwald con M. Arturo S. Hoffman. Desde Chicago emprendieron un largo viaje circular de tres meses (12 abril a 12 julio). Embarcados en Nueva- York y desembarcados en Gibraltar, viajando en bicicletas visitaron las principales ciudades de Andalucía, y luego Toledo, Madrid, Valladolid y Burgos, y saliendo de esta a las diez de la mañana llegaron a Silos por Covarrubias a las siete; al otro día saliendo a la una llegaron a las diez a Soria, de donde se dirigieron por tren a Zaragoza y Huesca. Nos escriben desde Lourdes que han atravesado el Pirineo a pesar de las nieves y continúan felizmente su viaje por Toulouse y Narbona etc. Esta es la primera vez que los ciclistas se atreven a recorrer nuestras sierras. «Siempre recordaremos, decían, con mucha gratitud a nuestros muy benévolos huéspedes, el interesante antiguo claustro y el jardín encantador». etc. etc.

Thank you for this interesting 1904 article about Arthur S. Hoffman's cycle trip in Spain. Bing translation:

SILOS BULLETIN (Monastery of Santo Domingo Silos (Burgos) Spain

July 1904 – Rev. No. 9 – pag. 407

Guests

Among the visitors we will cite three young Americans M. Laurence S. Williams and his brother M. Ellwald with M. Arturo S. Hoffman. From Chicago they undertook a long three-month circular trip (April 12 to July 12). Embarked in New York and landed in Gibraltar, traveling by bicycle visited the main cities of Andalusia, and then Toledo, Madrid, Valladolid and Burgos, and leaving this at ten o'clock in the morning they arrived at Silos by Covarrubias at seven o'clock; the next day leaving at one o'clock they arrived at ten to Soria, from where they went by train to Zaragoza and Huesca. They write to us from Lourdes that they have crossed the Pyrenees in spite of the snow and continue happily their journey through Toulouse and Narbonne etc. This is the first time that cyclists dare to cross our mountains. "We will always remember, they said, with much gratitude to our very benevolent guests, the interesting old cloister and the lovely garden." etc. etc.