John Russell, whose short story, The Lost God, was featured on this blog earlier started his career as a newspaperman, moved on to writing short stories for magazines and ended as a screenplay writer for Fox Studios. He worked on the screenplay of Frankenstein (1931), a few movies based on his own stories and Beau Geste (1926) among others.

This article about John Russell originally appeared in “The Morning Telegraph”, New York, on August 5, 1923. It’s the only biographical article about him that i’ve found.

|

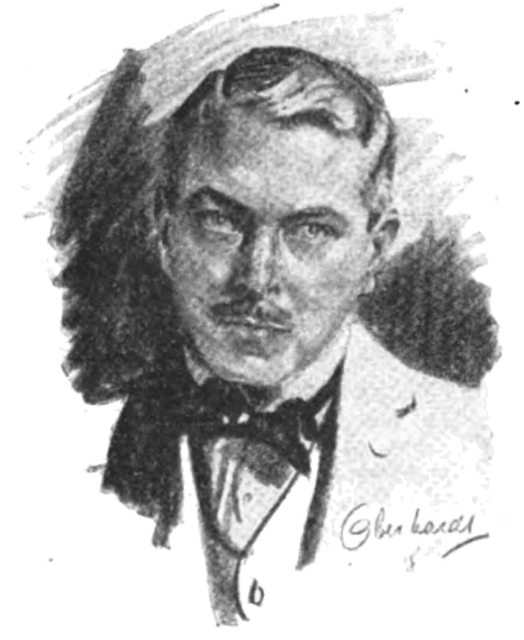

| Author John Russell (1885-1956) c. 1918 |

Being the Story of the Son of His Father, Who Has Written the Whole World Round To Gain Laurels Other Than Those That Came by Inheritance

IN the first place, John Russell is the son of Charles Edward Russell, newspaper editor and magazine writer able and extraordinary, and perhaps a story about the father should have preceded this about the son, for Charles Edward Russell is known to every newspaper office in the United States and Great Britain as one of the most vigorous and competent men who ever handled other men’s stories or wrote stronger ones of his own.

Briefly, Charles Edward Russell has established such a reputation as a go-getter of facts, which he presented vividly in newspapers, magazines and books, that we can well realize how hard it was for young John Russell to get out from under his father’s prestige.

Of himself, John Russell was born in Davenport, Iowa, April 22, 1885. The Russell family, before father became famous, was notable of its own self. Back in England great-grandfather Russells were eloquent divines of the Established Church. One of them was an early and most convincing advocate of temperance over a hundred years ago in the land where they were insulted — and still are — if any one spoke of taking away their toddies.

The immediate Grandfather Russell immigrated to the United States and became one of the pioneer newspaper owners in the Middle West, and a protagonist of the abolition of slavery in the days when such preachments were not at all popular, either.

Then comes Charles Edward Russell, whose sacrifices for his convictions have kept him a poor but honored man in journalism the country over, still unswervingly true to his faith in Americanism, as he sees and believes it and not as he might be more highly paid to see and to believe.

CHARLES EDWARD RUSSELL — and we must write an article concerning him sooner or later — was a newspaper reporter and took little John with him from city to city as he prospered and was promoted, or as he lost good jobs for writing and printing the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

One of the first toys young John had to play with was a printing press and, of course, he printed his own juvenile newspaper. This was “pi” for him. The family was then living in Brooklyn, where young John was going to school and fighting his way, as he still fights it. In his teens he entered the Pratt Institute, where he got expelled for miscellaneous deviltry; but the family moving from Brooklyn to Chicago about this time, young Russell got into Hyde Park School and when he was 10 had a narrow escape from becoming an actor, owing to the hit he made in school theatricals, playing one of the leading roles in “My Friend From India.”

But while the elder Russell has never become wealthy, he has always been a well paid and high-salaried man, and he went abroad as often as he could, and if he couldn’t go himself he sent his family there every summer, so young John had his mind broadened and his eyes opened to the Continental aspect of things, even in his nonage.

Returning to Chicago from Europe when 20 young Russell had an idea that he would become an artist and blacken white paper that way. While a student at the Northwestern University he studied drawing and portraiture at the Chicago Art Institute. He still has his drawing board, which his wife uses to make art objects in the shape of pies upon. For at the Northwestern University he met a Grace Nye Bolster, a fair co-ed, who married young John in 1906, just when he was 20 and she 18. She soon saw he would make a mighty poor artist, but had all the earmarks of his inheritance as a writer.

THE young married couple came to New York, where young John supported his wife in a style she was not accustomed to, but didn’t complain at, on $15 a week, as a reporter on the Herald, under City Editor Redding, who will be remembered as one of our very best newspaper men and poker there, according to Bennett and Hoyle.

Father Charles Edward Russell doing his famous “Soldiers of the Common Good” series of articles for Everybody’s magazine about this time, and he took the young couple to Europe with him, and they all went around the world together. Here it was young Russell got his first glimpse of the Pacific and the islands of the same that were to make him famous later, and he them.

Returning to New York, John Russell went back on the old Herald, and under ye old city editor, Redding, was made police reporter. He helped to cover the trial of Harry Thaw for the murder of Stanford White, he was hot on the trail of the elusive Chinaman who murdered Elsie Sigel, and he also covered the mysterious disappearance of Dorothy Arnold, the beautiful girl of wealthy family who dropped out of mortal ken one bright afternoon on Fifth avenue.

Those were the brave days. Only in New Jersey now do they have such murders and such mysteries. As a Police reporter it was John Russell’s duty to rouse a household at 2 A. M. and Inform the surprised and stricken family that father had just been horribly murdered in an obscure hotel, and what did they think about it, and would they give the inquiring reporter all the photographs and oil paintings they had of poor papa? If they did not give him the one he particularly wanted he had to snatch it and hie away with it.

THE HERALD now sent our hero to South America to meet the White Squadron of American battleships that had been sent down that way to awe the natives while the Panama Canal was being built. He met the fleet off the coast of Peru, he in a fishing smack hardly big enough to carry the Herald flag. He got his story and scored a beat on the cruise news by getting ashore at a lonely relay station at a cable’s end. Then he stopped at Panama and reported how the canal across the Isthmus was being dug.

As a reporter John Russell considers his best work was doing the story of President Taft’s Inauguration in the Herald office. There was a snowstorm that March 4th, and the wires were down and no accounts were coming through. Young Russell did the rewrite job of his life out of the files and the Statesman Year Book. James Gordon Bennett considered it as the most graphic story of the inauguration, and young Russell’s future was settled as a fiction writer.

But he had two hard years yet to serve, although they gave him experience as a fiction writer, for he was translated to the Sunday staff and that meant work, and plenty of it, as the Herald in those days spent very little money outside on its Sunday Magazine.

He did an average of three pages a week — features, interviews, fiction, verse and fillers. It was grand training. His semi-news features, “Would You Convict on Circumstantial Evidence” “Thrilling Lives,” “The Day of the Duel,” “The History of the Prize Ring,” and so on, are still standardized stories for newspaper Sunday magazines but other men are doing them now—mainly from the clippings of Russell’s original stories.

WHILE on the Herald he wrote a melodramatic fiction story for that paper, “The Society Wolf.” which was published in book form, but whose main circulation in this shape was the signed copies he gave to a wide circle of grafting friends. But it started him in the magazine field as a free lance.

He became one of the most persistent and welcome contributors to the Street & Smith popular fiction magazine. When good old Archie Sessions was editing the New Story Magazine young Russell used to write about half of it under seven different names. He traveled a lot about this time and thanks to his prolific pen, his income was most gratifying, although the rate paid him was only a cent and a half a word.

One day he sold a South Sea story to Collier’s and it was a hit and he got orders for all he could do that would be just as good and so he has been writing them ever since.

When America entered the war he served abroad on the Committee of Public Information under George Creel. This was a service that perhaps will never bring those who worked so hard on it, even George Creel, any undying fame. So far as actual credit goes John Russell does not claim as much for this work as should fall to the humblest American negro who at stevedored for our army in France. But it was a fascinating and necessary work — killing the enemy with paper bullets and selling American war effort to the disheartened Allies.

Like son, like father. Charles Edward Russell had volunteered for war work also and was put in charge of the American publicity offices in London, and young John went with him. They landed three million words of publicity a week in the British news. Then the elder Russell went on to France and John ran the London office and also did some confidential investigations in Ireland. Those were his crowded hours, but it gave him an opportunity to meet the best writers of Britain, who were also in war harness — writers like H. G. Wells, who was John Russell’s idea of all a great writer and a great man should be.

After the armistice John Russell took his third trip to the Pacific. His third and best. On this trip he covered Samoa and the Fiji Islands especially. He spent five months with the natives in Samoa, “on the mat,” as they say. He was adopted by a Samoan chief with the title of ‘Toleafoa Tusitala”. Tusitala means “story teller,” and it was the name the Samoans had previously given Robert Louis Stevenson. It was none of young Russell’s doings that the same title was wished on him, for none who write can exceed John Russell in reverence for R.L.S. And one of the most impressive moments of John Russell’s life was when he stood alone beside the grave on the mountain of the author of ‘Treasure Island’ and saw the glory of a great rainbow arch over it from the inland valleys.

Then John Russell toured widely through the Marquesan Islands to Australia, getting material for his future stories.

MEANWHILE his first South Sea Island stories had been published In America under the title of “The Red Mark.” If it was ever circulated in America John Russell was not aware of it. Certainly it had no sales and brought him in no royalties. But a publisher in England brought out an edition of “The Red Mark” under the title “Where the Pavement Ends” and under this title the neglected and rejected book in America ran through seventeen editions in England, became a best seller and is still going strong. Whereupon the American publisher revived it under the English title and has been kept busy bringing out editions of it ever since. The sixth American edition is now in press and the major stories to the book have been used in pictures under the same title — “Where the Pavement Ends” — and if you haven’t seen it you will, for it is one of the outstanding successes of the screen.

Such is fate and such is luck. It is to laugh!

John Russell’s latest book, “In Dark Places,” is just out, being published simultaneously in England and the United States, it has had appreciative reviews and its sale threatens to defy the old superstition that volumes of short stories never become best sellers.

After the success of “Where the Pavement Ends,” both in book and pictures, Russell was engaged by William Fox to go to Hollywood and write direct for the screen. On this occasion Mr. Fox remarked with a sigh that he hoped the arrangement would be satisfactory on both sides, but often when he had signed contracts with geniuses at big money genius would develop temperament that was trying, to say the least.

WHEREUPON young John Russell, son of Charles Edward Russell, but writer to his own right, assured the motion picture magnate that temperament was something that had never obsessed him. Young Russell further remarked that he had been dragged about by his father, Leo Redding, and other hard-boiled city editors for so many years that he would laugh himself to death if he ever should discover he had any temperament left whatsoever.

And so say us all good newspaper men and true, for verily this is so!