Robert Reeves, the author of the Cellini Smith stories in Black Mask, is a mysterious character. The veil of mystery around Reeves starts with his life. He seems to appear out of nowhere in the magazines, showing no evidence of newspaper work or other professions connected to the publishing business. Who was he? Where did he come from? Why did he stop writing so soon? When I couldn’t find out answers to these and other questions, it piqued my curiosity; the result is what you’re reading.

Reeves’ story is a story of the American immigrant’s dream. Reeves’ father was born in Csongrád, Hungary in 1882, the year of the Triple Alliance between the empires of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. War clouds were looming over Europe as alliances were made and broken. In 1904, Britain, France and Russia formed the opposing Triple Entente. If it wasn’t clear to any young man that war would break out soon, they’d have to be blind and deaf. Added to these was rapid population growth in Hungary, which depressed wages and drove up unemployment.

The Triple Entente was Great Britain, France and Russia.

Reeve’s father, like many other Eastern Europeans, looked westward. He emigrated to America, arriving in New York in 1910 with his family. Which at this point was his wife and one son, Theodore, born in Hungary. Reeves’ father’s full name, which I omitted to mention till now, was Zoltan Rosenfeld. When they migrated, Zoltan gave his profession as cabinet maker/carpenter. Zoltan’s wife was Yetta Edelstein, born in 1887 in Hungary; their first son Theodore was born in Hungary in 1910. Robert was born on 24 January 1912. Theodore and Robert studied in the public schools of New York.

In 1921, for reasons that are unclear, Zoltan decided to change his entire family’s surname to Reeves. He may have wanted to make sure that his sons didn’t have to face prejudice against Eastern European immigrants, who were stereotyped as cultural inferiors.

If that was his motivation, it worked. Robert went to New York University, where he studied History, English and Anthropology. Then he worked a variety of jobs on the stage, including carpentry, casting, stage manager, producer etc. In 1930, the family was still in New York.

Sometime after 1935, brother Theodore moved across the country to California and the rest of the family followed. In the 1940 census, Theodore was the head of the family, working as a screenwriter for a movie studio; earning over five thousand dollars that year. Zoltan was working as a prop man for a studio; he earned over a thousand dollars. Yetta and Robert lived with them, their listed income was zero.

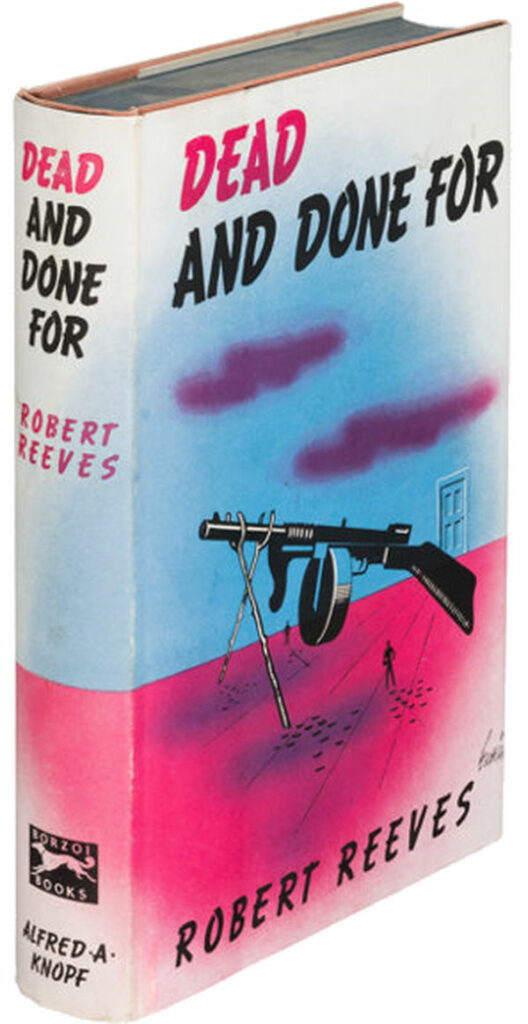

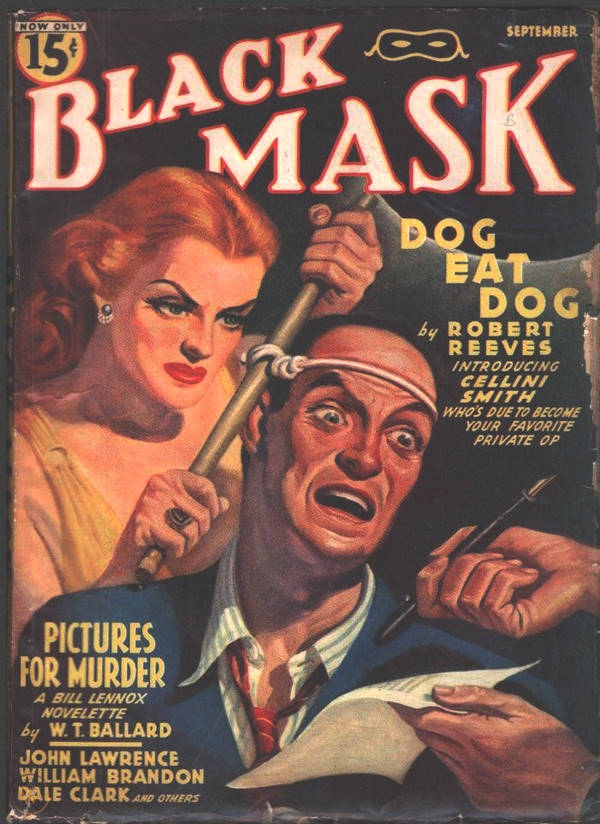

Though Robert had sold four stories to the pulps from 1930 to 1936, his breakthrough was with the first Cellini Smith mystery, Dead and done for, in 1939. Published as a book by Knopf, it met with moderate success. Enough that Reeves managed to sell Black Mask a serial, Dog eat Dog, in 1940.

In 1942, Reeves enlisted in the US Army, and was assigned to the Army Air Corps. Then he was sent as a publicity man to the 500th Bombardment Squadron of the 345th Bombardment Group. The 500th Bomb Squadron, called the Rough Raiders, entered combat in June 1943. Starting from New Guinea, the squadron’s combat objective was to take control or neutralize Japanese presence on the Pacific islands. After control was established, the Squadron flew low-level strafer-bombing missions against Japanese shipping. The 500th squadron had the largest loss of men and planes in the 345th bomb group and also inflicted the greatest amount of destruction on the Japanese.

B-29 bombers of the 500th Bomb Squadron in action

While serving with the Air Corps, Reeves often hosted newspaper reporters and movie makers touring the front lines, among them Dalton Trumbo. Reeves also continued writing for the pulps, perhaps to keep his hand in for his planned return.

On 11 July 1945, an aircraft from the 500th Bomb Squadron was shot down in Suo Ko (Su’ao) Bay in Formosa (Taiwan). Major Bob Canning, commander of the flight, was flying the lead plane; Capt. Robert Reeves was with him as a photographer from the Fifth Air Force public relations department. The rest of the crew were from the West Coast.

Reading between the lines, the craft might have survived that day if Reeves was absent. The pilot was leading a flight of four planes, looking for enemy shipping to destroy; Reeves was to photograph their work and present it to the public. They found nothing that day; so as they approached Formosa, Major Canning looked for targets on shore. They bombed the lighthouse at Sandiaojiao, the easternmost point on the island, and then proceeded to Su’ao. There Major Canning’s plane was was struck by intense anti-aircraft artillery fire and exploded. The other planes were also damaged, but didn’t crash.

The crew’s bodies were all recovered. Only radio operator Schierman’s body was identified and taken to Shanghai, China, for burial. The remaining five crew members were buried together and later re-interred in Fort McPherson National Cemetery, Maxwell, Nebraska.

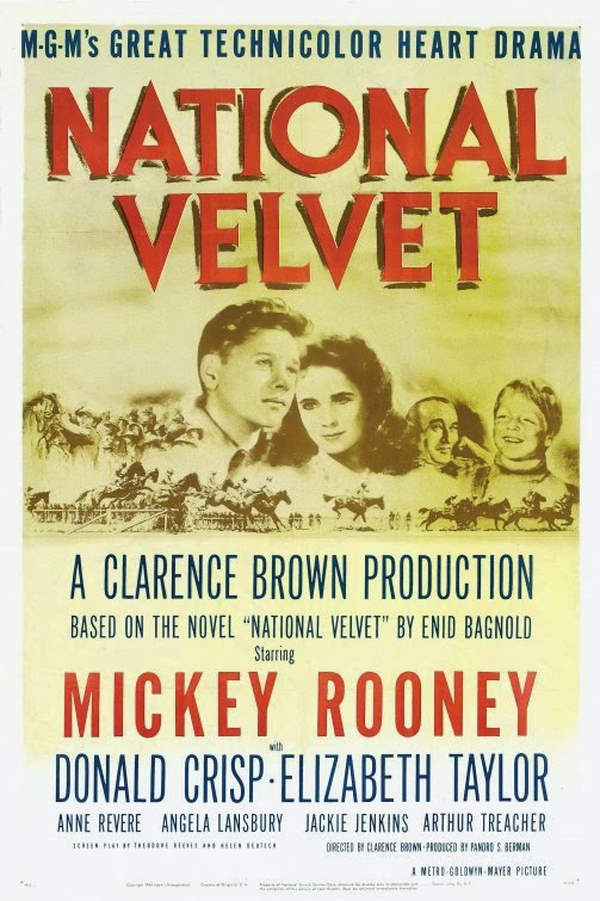

Reeves’ father Zoltan died in 1947. Brother Theodore had a successful career in Hollywood, where he wrote screenplays for over a dozen movies. Among them was National Velvet (1944), which made Elizabeth Taylor into a teen star. Theodore died in 1973, leaving behind his wife Margaret and his mother, Yetta. Yetta, the longest lived of the family, died in 1979. I don’t believe either of the brothers had any children. Their works are their memorial.

I always thought it was a shame that Robert Reeves had his career cut short by his death in WW II. He was an exceptional writer and one of the very best of the Ken White authors who worked for Black Mask. Steeger Books is reprinting his fiction.