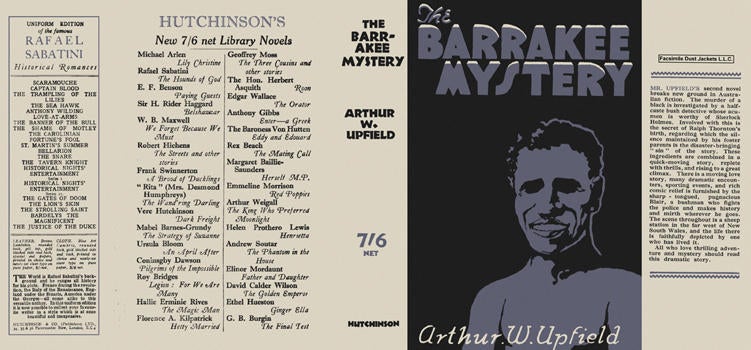

In 1929, British-born Australian Arthur Upfield(1890-1964) wrote and published his second book, The Barrakee Mystery. Published first in England by Hutchinson, the book was originally written in the 1920s, when Upfield was working as a cook in the Australian Outback. Twice rewritten and substantially altered, the book had good reviews in London, Manchester and in his adopted home, Australia. It was published by Dorrance in the USA. However, for whatever reason, subsequent Boney novels weren’t published in the USA till the 1940s, when many Americans were posted to Australia and their families, eager to find out more, read Upfield’s books.

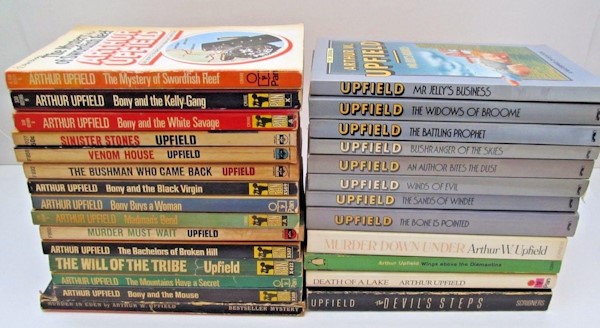

Encouraged by reviews, publishers’ sales reports and fan mail from all over the world, Upfield wrote twenty-eight Boney novels from 1960 to 1963. A last Boney novel, The Lake Frome Monster, came out in 1966 after his death, completed from notes left by Upfield. In his time, Boney was a publishing phenomenon translated into German and French, read on radio, made into radio plays and a TV series in the early 1970s and influenced writers like Tony Hillerman.

I read the complete series over the last two months, finding a copy in a box I hadn’t opened in over a decade. The rest, thankfully, were in the same box. I could review the books one by one, but I’m taking an easier way out. I’m going to say what I felt about the overall series and only review books I liked.

Let’s start with the hero. Boney, child of a European father and an Aboriginal mother, was orphaned soon after birth. His father was nowhere to be found, and his mother died holding Boney in her arms. Rescued and fostered by a nurse, Boney manages to acquire a university education and rise up in society to the rank of detective inspector of police, thumbing his nose at authority and bringing justice to solve crime. Upfield claimed to be inspired by a native tracker he had known, but later research reveals the inspiration to have been a mirage. Upfield was a story-teller, often bending truth and probability to favor a good narrative.

In the early books, much is made of Boney having to succeed at his career or succumb to his native heritage. The books and characters in the books often refer to him as a half-caste, sometimes admiringly, sometimes not. Clearly, the book reflects the attitudes of times less enlightened than ours.

In the early stories, Boney clearly feels trapped in his position, always needing to succeed, to prove himself worthy again and again. This insecurity slowly recedes in subsequent novels, though Upfield would return to the same theme multiple times. One has to ask: Did Upfield really believe that a character like Boney could exist in real life? Did he believe that such a character could bridge the racial gulfs of his environment in those years? And did he think that reversion to type would always be a threat, overriding individual will? It’s hard to decide if Upfield believed any of this or whether he was just pointing out the prevalent beliefs of the time without subscribing to them.

Upfield’s characterization feels weak. Boney is mostly a non-entity with zero personal life, beyond periodic mentions of his adored wife and children. Whenever Upfield has to describe Boney, he falls back on Boney’s blue eyes and occasionally his gaudy taste in undergarments and nightclothes, a rather unsubtle way to convey that a civilized veneer concealed the native temperament beneath. In Upfield’s defence, Boney shows respect to both parts of his heritage, never feeling compelled to disown either part, but managing to mingle in both cultures without losing himself. Rarely did a supporting character burn himself into my memory. Women in Upfield’s writing mostly lived on pedestals, going about their domestic routine and guiding their menfolk.

Most of his books are slim paperbacks, rarely exceeding two hundred and fifty pages. His plots are correspondingly thin. Most can be summarized in a paragraph. If you like only fairplay, well clued mysteries like Agatha Christie’s, don’t bother reading Upfield.

So why, given his thin plots, weak characterization and often unsubtle racism, would you want to read Upfield today? The answer is in, crazily enough, two of those defects. Lean plots and cardboard characters leave plenty of room for the real star of the story, Australia, to make itself known and seen. Even today, nearly a hundred years after Boney’s first case, the Australian interior is sparsely populated, extremely dangerous if you go off the tourist trails, perhaps as unknown to most people, and still as beautiful as Upfield describes. Like many sparsely populated places with little surface water, the harsh climate shapes the people; the tough environment tolerates only the best adapted and smartest. One mistake and you’re dead. Such a land inspires respect and love in those who can adapt to it.

The Boney books I liked best put this land in the center. Plot is spasmodic; characters flit across the backdrop and disappear, lost in the vastness. Except Boney, who is as much at home at a tea party in a sheep station as he is at tracking or working in the bush.

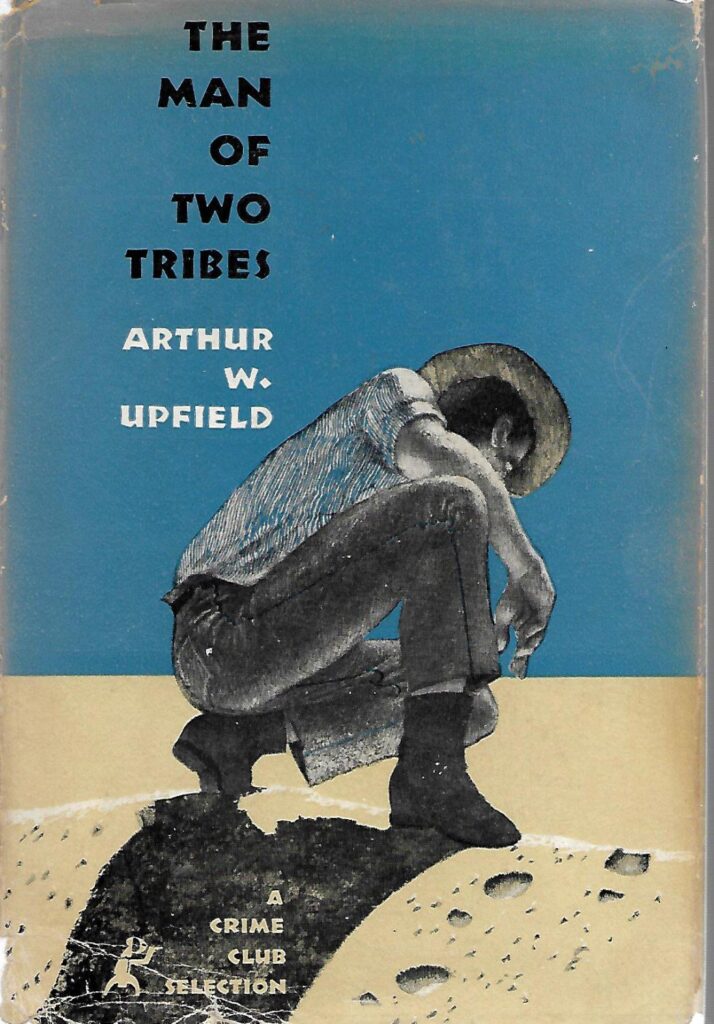

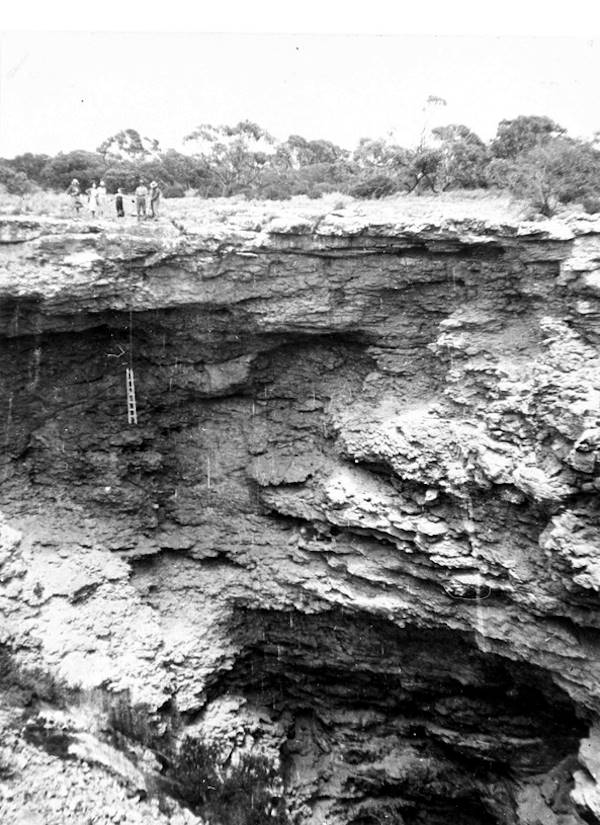

First, I recommend Man of Two Tribes. The plot is just barely plausible: Relatives of a murder victim kidnap criminals who have not paid enough for their crimes, or have escaped the justice system altogether. They imprison these criminals together in a remote, unreachable and deep subterranean cave in Nullarbor, a stony, treeless and mostly featureless limestone plain honeycombed with caves, around 200,000 square kilometers in area.

Boney, arriving on the scene in search of one of the missing criminals, is caught up in their net and imprisoned along with the criminals in a cave. This occupies about nine chapters of the book.

In another eight chapters, Boney forms a team and leads it on an expedition across the plain to the nearest homestead. The sun is merciless, shade non-existent. They have to travel in the daytime, travel in the night risks both injury (pits and rocks are hidden) and losing their way. There are no landmarks to guide Boney. The fatigue of walking, the waterless landscape, the monotony and silence all act on the travelers.

The morale-slaying Plain took them instantly to itself, for they were like mariners leaving safe anchorage when leaving the belt of bluebush. No ship under them, no steel walls about them. Soon there was no place to leave astern and no place to steam ahead.

There was only the nightmarish uniformity of flat plain kept steady by a cloudless sky. You can ride a camel, a horse, a jeep, and close your mind to this Nullarbor, find exquisite relief in the cinema programme the mind will screen. But on your feet, you have to walk with eyes open and the mind naked to reality.

And when the sun said: “I’ve had enough of looking at you,” and turned to more interesting insects below, they had no cave, no hole in the ground, no bluebush amid which to crouch. The sky caught fire from the sun’s hot trail and the high-flung dust wove mighty draperies of scarlet before Space, shutting it out, as though blown upon by Evil itself. The colour in the folds deepened to magenta, then to black, and finally blessed night came.

See this video of the Nullarbor from half a century back.

And then imagine what would have been like when the novel was published in the 1950s.

Boney and the Black Virgin takes place in a bleak landscape in drought-ridden New South Wales, with people and animals tormented outwardly by drought and inwardly by dark thoughts, culminating in a stunning tragedy. The reasons for the tragedy indict contemporary Australian society. Naturally, it was almost completely ignored by the local newspapers and magazines, who would rather stay away from controversy. Those who did review it ignored the racial element and offered little praise. The Sydney Morning Herald called the plot silly. I was more interested by the social element and the description of drought than the mystery.

Death of a Lake has vivid descriptions of drought, again, this time revealing past crimes in addition to fomenting new. A lake that appears and disappears with rain and flooding, is disappearing slowly with the passing months. Boney expects to find the corpse of a man reported missing, and with the corpse, clues to his killer. The descriptions of the scenery are vivid. The death of the lake mattered more to me than the death of the murder victim.

Due to his lifelong habit of waking at dawn Boney witnessed the first throe of the coming death of Lake Otway. On waking he proceeded, as usual, to roll a cigarette and while doing so recalled how the pelicans had congregated in great crowds on the previous evening. He had slept on the top of his bedclothes, and it was now as hot as when he had fallen asleep.

On bare feet, he passed out to the veranda and sauntered to its end overlooking the Lake.

The birds still congregated. He counted eleven masses of them in a rough line along the lake’s centre, each mass looking like an island on which now and then someone waved a white flag. The flag was the white of under-wings when a bird raised itself and flapped its wings as a cat will stretch to limber up. The sky slowly acknowledged the threat of the sun. The surface of the Lake caught and held the same threat, and when the edge of the sun lifted above the trees behind Johnson’s Well, the first bird took off.

The unit detached itself from a mass, flapped its great wings, paddled strongly and began to lift. When air-borne, the bird took the long upward slant as though bored with flying. Another bird followed, a third, and so on to form a chain being drawn up to the burnished sky by a magnetic sun. The same routine was followed by the other congregations of pelicans, until there were eleven long black chains over Lake Otway, each link rhythmically waving its white flag.

When a thousand feet above the water, the leader of each chain rested upon outspread pinions, and those following gained position each side of the leader and also rested. Thus a fleet was formed, which proceeded to gain further height, every “ship” of each “fleet” alternately winging and resting in perfect unison.

The chains having been wound up and the fleets formed, the sky was ribbed and curved with black-and-white ships, each with its golden prow. Like ten thousand Argosies, they sailed before the sun, fleet above fleet, in circles great and small as though the commanders waited for sailing orders.

Presently the fleets grandly departed, one following the other, the units of every fleet in line abreast, sailing away to the north till the sky absorbed them. Fifteen, twenty years hence that same sky would produce similar fleets of Argosies to sail down the air-ways and harbor on Lake Otway reborn.

“They must have felt the bottom with their paddlers,” Carney said, and Boney turned to the young man whose face defied sunburn and whose large brown eyes seemed always to be laughing.

In The Bone is Pointed, Boney investigates the disappearance and possible murder of a station foreman disliked by aboriginal and station worker alike. No one wants the mystery solved, for the solution would involve some level of outside interference in the station and its inhabitants. Boney, working in an extremely hostile physical and psychological environment, uncovers some traces of foul play. The local aboriginals, trying to drive Boney away, point the bone at him. Pointing the bone is casting a curse using the tribe’s store of magic. The descriptions of tracking and the rituals accompanying the casting of the curse are interesting.

Considering the lapse of time since Anderson rode out never to be seen again, the task of solving the mystery of his disappearance might well have seemed hopeless to a lesser man. Boney had no starting point such as the body of a murdered man, nor any clue to provide a basis for theory from which fact might emerge. What had happened to Anderson, to his hat, to his stockwhip, to the horse’s neck-rope? Where now were these three articles and the man? For days and weeks stockmen and the aborigines had hunted and found nothing. It was as though the falling rain were acid that dissolved solids and washed them into the thirsty earth.

…

After five months it would have been stupid to expect to find The Black Emperor’s tracks on sandy ground, on loose surfaces such as composed most of the plain, or on surfaces scoured by the rainwater that followed Anderson’s disappearance. The claypans, however, always gave promise, for they could retain imprints for years, even if the imprints required the magnifying eyes of a Napoleon Bonaparte to see them. And, at irregular spaces across these claypans, Boney thought he could discern the faintest of indentations that could have been made by a horse before the last rain fell. He thought it, but he could not be sure.

For nearly eight miles Boney rode northward, again to dismount at the edge of the maze of sand-dunes stretching away into Mount Lester Station from Green Swamp. Here, where the fence rose from the comparatively level plain to surmount the dunes like a switchback railway, Boney and Lacy surmised Anderson to have stopped for lunch. A little way back from the fence grew a solitary leopardwood-tree, to which The Black Emperor could have been conveniently roped for the lunch hour.

Boney was now thrilling as might a bloodhound when in sight of the fugitive. He walked his horse to a tree distant from the leopardwood, neck-roped her to it, then returned to the leopardwood and began a careful examination of its trunk at about the height of the black gelding.

Now the bark of this tree is soft and spotted and greengrey, and Boney hoped to find on it the mark made by rope friction caused by an impatient horse. He found no mark. The tree grew above ground covered with fine sand, and those of its roots exposed he examined inch by inch for signs of injury from contact with an impatient horse’s stamping hoof. He found no such injury. With the point of a stick he dug and prodded the soft surface, hoping to uncover spoor buried by wind-driven sand. He found no spoor, but he unearthed a layer of white ash, caked by the rain and covered by dry sand blown over it after the rain. Here Anderson had made his lunch fire.

Bony buys a woman has Bony trying to understand the kidnapping of a child and the murder of her mother at a remote sheep station. The child may still be alive, the kidnapper hunted by everyone around yet managing to slip through their net. Boney has to find a way to the girl and the killer. A great description of secret locations and paths in a drying lake.

The dingo pad was seldom more than twelve inches wide, and often was reduced to four inches. At some places it was quite distinct; at others only a good tracker could follow it. When he was three miles from shore, the pad wound about a great deal, which aroused his interest, because, under normal circumstances, a travelling dog proceeds straighter than does a man. Presently the pad became less twisted, and gave him his first surprise… a narrow strip of hard sun-baked mud.

…

The day wore on, and he was beginning to wonder what kind of night he would spend if he had to camp on this narrow dog pad, when again the pad angled sharply. It had reached the border of a large area pitted by open holes the size of a florin. The dogs had not crossed it, had skirted it, and he saw why when a green finger emerged from one of the holes, beckoned to him, sank again into the mud. Then while he watched, other green fingers appeared, beckoned, and disappeared.

Curiosity was suddenly submerged by desire to get away from this place of the unknown; the beckoning fingers became the miasma of a nightmare, and the board shoes the leaden feet of it.

…

Until the sun went down, it was not possible to see land, and Bony occupied time by testing for water under the mud. He had found a short swathe of tree debris, among which was a four-foot stick, and although he didn’t find water even by seepage, he did uncover the mystery of the erratic course of the dingo pad. The true bottom of Lake Eyre was not flat, as the surface of the mud overlay indicated, but rather was similar to the sea bottom, with its valleys and hills and mountains. The dogs followed the summit of ridges, and the two areas of hardened mud merely covered the tops of subterranean hillocks; and that area of mud from which upthrust those extraordinary green fingers must mark a valley or chasm.

Those are the books I’d recommend someone else try. If you liked them, you might want to explore Australia with Boney. Or in person.

I’m enjoying all the Bony books again after 40+ years and also enjoyed reading your comments. I agree that Australia is the main character of the books. Also enjoyed your travels across the Nullabor. We also drove it back in the 1970s, my main memory being looking off the cliffs to the southern ocean. I wish I could recall more.

Hi – I thought you’d like to know that a new book about the making of the “Boney” TV series has just been released! “BONEY – Following the Footprints” by Roger Mitchell can be found on Amazon in all countries, and as the computers at all the online bookshops around the world update, it’ll start showing up there too.

You’ll find stories about Upfield’s original novels (not that YOU need those!), the producers who went against the odds to create a TV series starring a mixed-race detective, the search for an actor, and the realities (good, bad and absolutely dreadful) of filming in the Outback. You’ll read exclusive interviews with the people who made it, details of every episode, biographies of the actors and an investigation into the Aboriginal history that made DI Napoleon Bonaparte such an unlikely hero. You’ll also see photos from personal collections, unseen documents and long-lost magazines, posters and publicity material.

It has 270 pages and more than 100 photos, many of them never seen before. It’s a real treat for “Boney” and TV detective fans.

Thanks a lot,

Roger Mitchell.