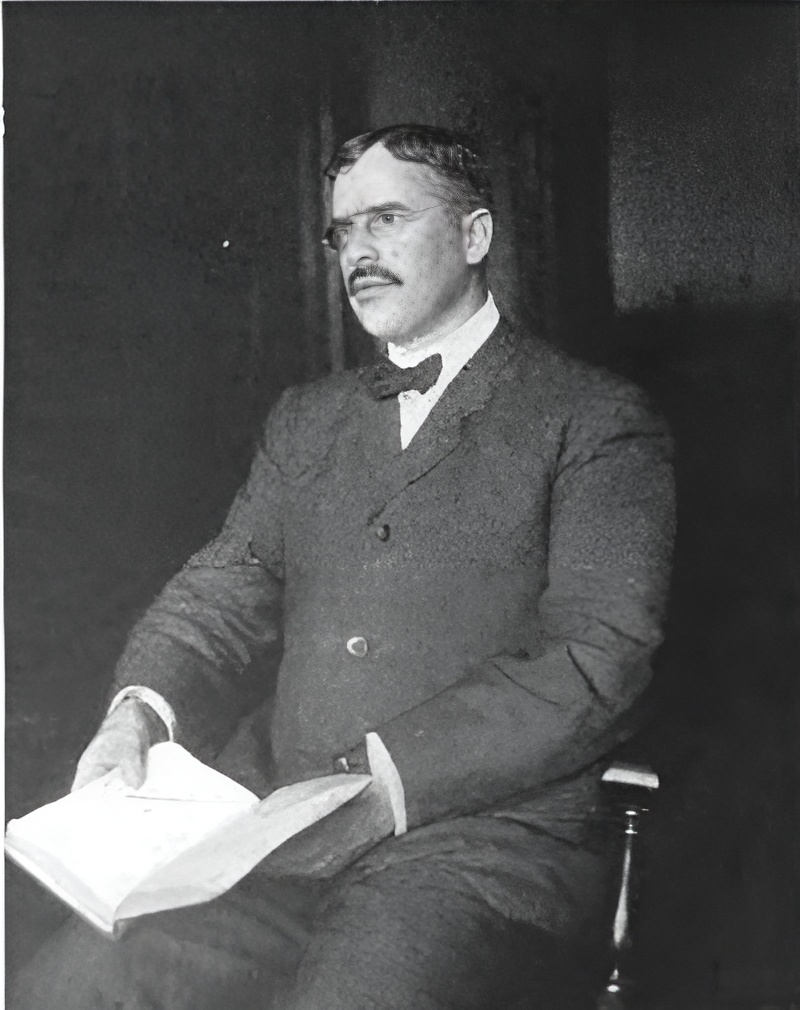

This article by and about B. M. Bower, author of Chip of the Flying U and many other novels and stories, appeared in the December 10, 1928 issue of Western Cattle Markets and News.

My Own Tally Sheet

By B. M. Bower

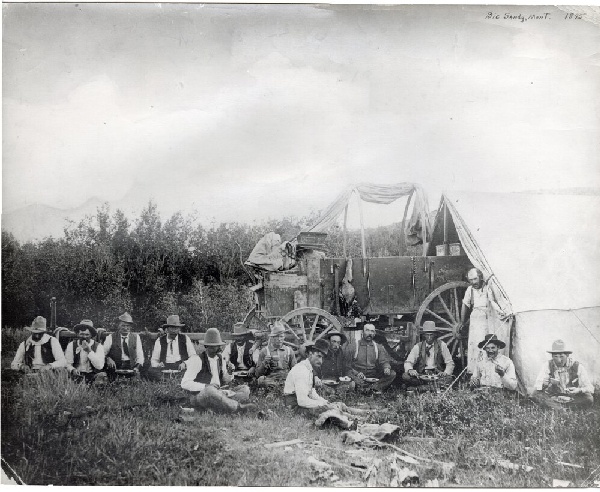

Note—B. M. Bower, author of “Chip of the Flying U,” which was written in the mountain cabin pictured above, and author of many other Western stories, gives us here her “own tally sheet” on how she became a writer of Western cowboy stories. Eight of B. M. Bowers stories, including “Chip of the Flying U,” have been produced in motion pictures featuring Hoot Gibson, the most recent being “Rodeo.”

WELL, Chip, here we are talking to a bunch of real cattlemen after a few years of knocking about by ourselves. I’ll tell you one thing and that is that I’m going to let out a little about myself this time instead of always writing about my “Happy Family.” Not that I think so much of myself, but there seems to be a kind of personality craving around this outfit of cattlemen in convention here in old San Francisco, that demands something—for lack of a better name— well call just plain gossip.

Here is a message I got this morning: “Instead of writing about the inimitable fellow, Chip, and that restless line rider, Hopeful Bill, tell us about yourself; and ye gods, let us know what the B. M. stands for!”

I told you it was to be real gossip, so let’s give them an earful. But before we do, let me ask what you think of Hopeful Bill. I first met him in Seattle and he was complaining about the fog and rain up there.

“I don’t like it,” he says. “I want to see men’s eyes light up with a gleam of humanity when I look into them on the street. If I smile—and smile I do—I like to see a smile flash back at me. Because we’re both traveling the same trail, you and I. We have the same problems to solve, the same disappointments, the same joys. And why shouldn’t we look out on the world kindly? No matter how he acts or what he’s doing, every man on earth is looking for the same thing. Until he finds that thing, he’s darned lonesome, away down inside. He don’t have to admit it, but it’s there.”

And again he says: “Starting out this way, not knowing where night will find me, I feel as if I’m swimming in the limitless ocean of Life. I’m hunting sunshine. If I find it in the eyes of the people I meet on the road, all the better. That’s the kind of sunshine that makes the world a place to be proud of. If I can put it into a face, the reflection I get is joy; the kind of joy that follows you away down the road.”

Well, he found sunshine all right, here in California, and he has been here some time. But lie’s on the move again now. Some Bill!

But as to the subject of myself, you see the B. stands for Bertha and the M. for Muzzy. Now you have it. I am a woman and always have been, even if I have associated with cowboys all my life.

Muzzy is a corruption of the French name De Musset and my ancestor was one of the family of Alfred De Musset, that temperamental French poet and playwright. I inherited the name but not the temperament, I hope. After my ancestor emigrated from France to the American Colonies the name degenerated to Muzzey.

I was born in Cleveland, Le Sueur county, Minnesota, a direct descendant of Myles Standish and of Robert Muzzy, my great-great grandfather, who was a captain in the French and Indian War of 1759, in the Revolutionary War of 1776 and in the Indian War under General Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1797.

The wife of Robert Muzzy Junior was Martha Morse, who was the daughter of Samuel B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph.

The pioneering strain seems to have come down in the family without much adulteration. My father was always moving West, and went into Minnesota when it was still a territory. He built a log cabin in what was known as the Big Woods of Minnesota, and literally hewed himself a home out of the wilderness, and I was born in this log cabin in a wilderness. I have been very partial to log cabins ever since, but my first memory of a fireplace was in Idaho when I was about 18 years old.

Being of pioneer stock, always moving West, my education suffered many interruptions, but I was considered a very precocious student, and soon went through the grades and into high school. Then my father moved into Montana (to Great Falls), the year after the railroad was built. Two box cars were used for the depot and express office at Great Falls for two or three years after we arrived. I had just made my application to enter the State University of Minnesota when I decided to go West with Dad.

Fortunately, however. Dad was qualified to teach me the things I should have been learning at the university; he even taught me drafting and music. It was there at Great Falls that I began to absorb (unconsciously at first) the atmosphere of the West. Having that pioneer blood in my veins, almost the first thing I did was to accept an invitation to teach school 50 miles up in the mountains amongst the bears and cowboys and mountain lions. We drove in a lumber wagon to the valley, where a few settlers were tucked away in the coulees, while the cattle and horses ranged the hills.

I must have had as many as five pupils! They cleared out an old milk house for me, and rustled a table, and boxes for the kids to sit on. I used a square of tar-paper for a blackboard at first until someone painted a board black for me.

On windy days clods of dirt would rattle down from the roof and we could see our breaths over the books—but I had a horse to ride, and I learned to ride him cowboy style. And that atoned for all the little drawbacks. I am sure that I was a very meek, demure, young school ma’am, but for all that, feuds arose amongst the cowpunchers.

From that time on I lived in the range country, and learned the ways and customs almost as well as if I were a man. I began writing, mostly to pass the time away while I was living in a cabin in the very heart of the cow country. “Chip of the Flying U” was my first long story. I used to let certain of the more favored ones read chapters of it as I wrote. Then they would discuss it gravely with me, criticizing what they called the “Cowology,” when they could find anything wrong. I suppose I might almost say that the T. L. cowboys helped write “Chip.”

From that time I was ruined for the commonplace life of a mere housewife. I lived in a dream world of Bower characters and inevitably those characters came to life on paper. They still do some riding up out of the unknown to find themselves at last on the printed page.

Besides “Chip of the Flying U,” I have written some forty novels and 150 short stories, all published in magazines, save two.

Eight stories, namely “Points West,” “Haywire,” “Rodeo,” “Chip of the Flying U,” “The Range Dwellers,” “The Ranch at the Wolverine,” “Good Indian” and “The Uphill Climb,” have appeared as motion pictures. The last one to have found its way to the screen was the “Rodeo,” made by Hoot Gibson during Tex Austin’s Rodeo held in Chicago this last summer. Incidentally, Mr. Gibson says that and “Chip of the Flying U” are the best pictures he has ever made.

I began writing in 1901, serving my apprenticeship in short stories, and collecting the usual number of rejection slips.

“Chip of the Flying U” was written in 1902, but, knowing neither the market nor the usual method of procedure, the story was not placed until 1904, when it was published as a novelette in the second number of the Popular Magazine. The editor frankly wrote that he expected the story to prove a circulation builder for his magazine—which at the time was pioneering as an all-fiction magazine.

On May 13, 1904, the editor wrote: “Personally, I am delighted to get the story (“Chip of the Flying U”) as I think it will prove to be a circulation builder for the Popular Magazine. We are endeavoring to improve the material we are publishing in the Popular, and I think this is about in line with the stories we have in mind for publication.

On September 19, 1904, the same editor had this to say: “We believe you will be interested to learn that “Chip of the Flying U” has made quite a sensation. We are in receipt of letters from all sorts and conditions of readers warmly congratulating us on this story. We would be very glad to have you consider another novelette of range life for the Popular Magazine.”

On August 23, 1904, the editor of Ainslee’s Magazine said in reference to my work: “We have come in the past year to feel so sure of the quality of your work that we should not think of imposing any limitations upon you. Since your first story came to us, your progress has been almost unique for its rapidity and steadiness. It is no more than the truth to say that in this office you occupy a position shared by only a very few of our most valued contributors.”

Another editor wrote on June 20, 1904: “It seems to us here that you have progressed in your work with unusual rapidity. I have been personally watching new writers for some eight years now, and with possibly the one exception of O. Henry, I can remember no one who has gone so far in so short a time. It is now only a little over a year since we bought the first story from you, and we have been buying almost everything you have sent us since then. You do not have the very uneven streak which some writers develop.”

The pen name, “B. M. Bower” was invented for me by Mr. Gilman Hall, then editor of Ainslee’s, and he did it in this wise: “We have talked over the question of your name here, and it seems to us that it would be better to write it B. M. Bower. We think that both this story and At the Grey Wolfs Den would be better placed before the public if it is not known that a woman wrote them. So we have ventured to sign your name B. M. Bower in the May number and that we can not change. We want to do the same with this story.”

So now you know B. M. Bower is a woman and you know how she became a Western story writer.

I’m a related to Martha. Will continue later