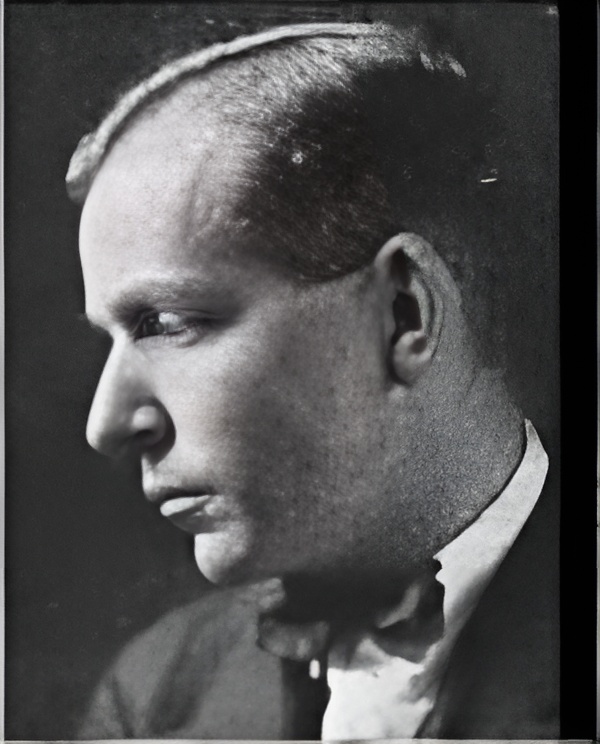

Charles Willard Fairchild was born on 18 November 1886 in Marinette, Wisconsin. His parents were Charles Marsh Fairchild and Sarah Jane “Jennie” Cook of Toledo, Ohio. Charles Marsh Fairchild was a versatile businessman, running a drug store, a newspaper and a steel company, in that order. Charles Willard grew up in Wisconsin and Toledo, Ohio.

He got his art education at the Chicago Fine Arts Academy. It’s likely he worked as a commercial artist for firms in and around the Great Lakes: Chicago, Toledo and Cleveland before moving to New York. His early work appeared on the covers of All-Story magazine, followed by interiors for McClure’s and covers for The Woman’s Magazine and The Countryside.

He got married in New York City in 1914, so we know he had arrived there by that time, probably earlier. His career was suspended in 1916 when he enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War 1. He left the army in 1918.

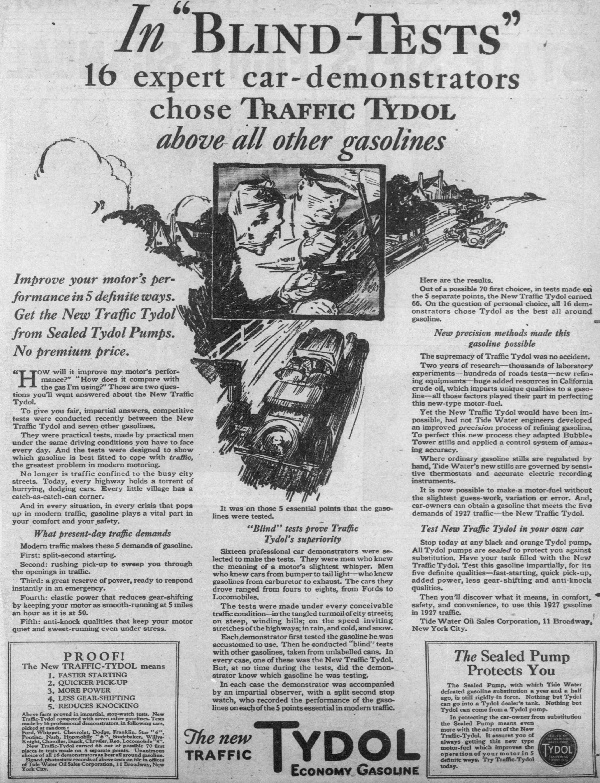

In the 1920s, his name appears in various trade journals as the art director for a succession of advertising firms, of which the biggest was BBDO. As Art Director, he was responsible for coordinating layouts and making sure the advertising design was in tune with the client’s expectations. One example:

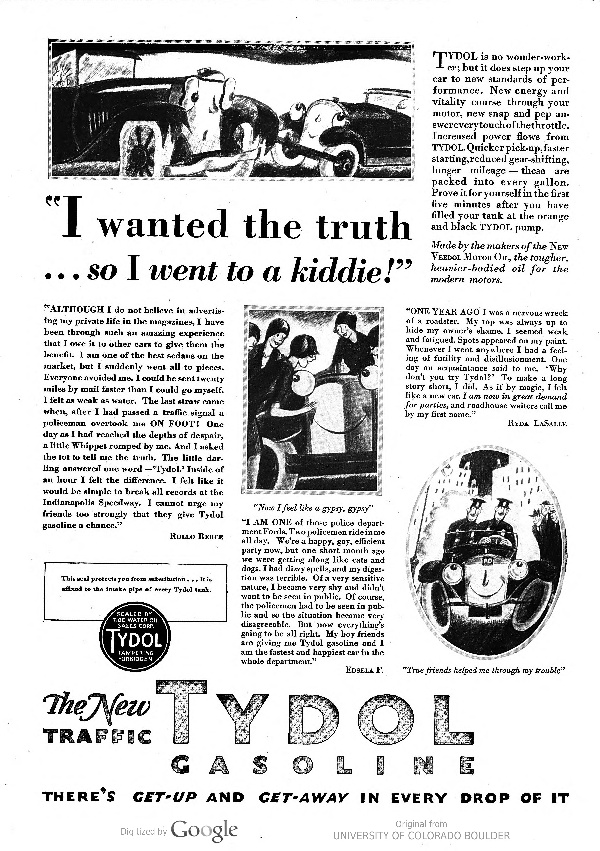

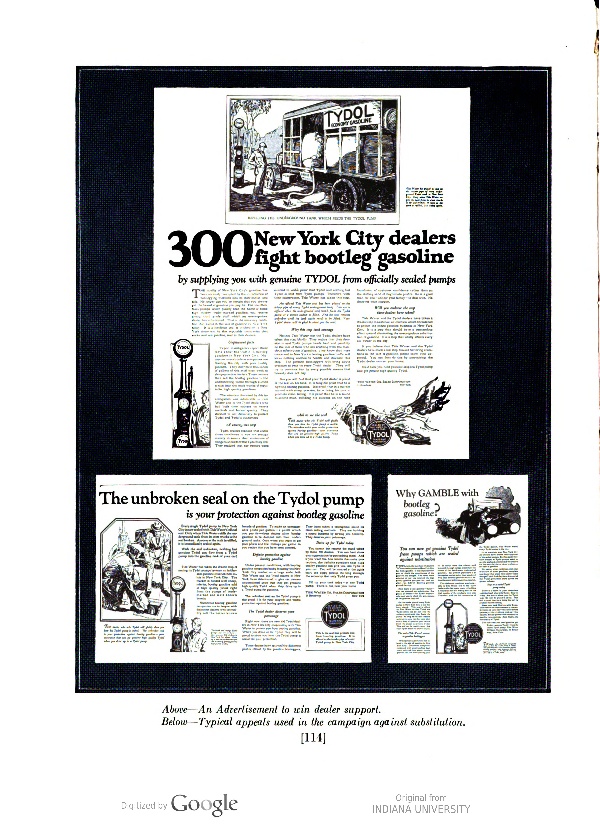

The engineers of the Tide Water Oil company recently developed a new gasoline expressly refined to meet modern driving conditions. It was decided to call this motor fuel “Traffic Tydol” and to advertise It throughout the spring in leading newspapers from Maine to Maryland.

But the Illustrations finally used were something entirely different from those used In advertising any kindred product. They have created widespread discussion wherever they have appeared. And the sales of the gasoline that they advertise have Increased tremendously.

“Good advertising should have just as much news value as the newspaper Itself. It must compel attention, otherwise it gets no readers. In this connection note radio broadcasting. Almost every program sent out contains some Jazz music. Why? Just to say ‘because It’s popular’ sidesteps the issue. The age demands it. This Is an age of speed—excitement. Jazz has what you might call ‘news value’ because It’s expressive of the up-to-the-minute trend In all of us.”

“The movies — German movies like ‘Variety’ particularly— have familiarized the public with what we call modernistic art. This art is the counterpart in light and shade drawing of jazz in music. It has been used before by some smart stores and for women’s fashions, but never before, we believe, for any staple product like gasoline. And never before in such big space advertisements.”

“Note that we have not been extreme. We have not been so absurd but that any child would recognize typical traffic scenes. In the automobiles themselves there is practically no distortion. They are snappy looking and well-drawn.”

When questioned about the artists who did this work, Mr. Fairchild said, “We used the best artists we could get in the modernistic field—Clayton Knight who illustrated the airplane story, ‘War Birds’ in Liberty; Russell Patterson, well known magazine illustrator; Mr. George Illion who is well known for his futuristic drawings and posters both here and abroad; and William Reinecke and Earl Freeman, both popular and able artists in the modern field.

“Take a drive in traffic through any city. See If these men with their straight shafts of diverging light and shade haven’t caught the feeling that you get. The helter-skelter of modern driving is confusing—should be expressed in sharp eccentric angles. And the shadows of modern skyscrapers throw a crazy pattern over every street. At night the streams of light from headlights produce the same effect.”

When asked if he believed whether this type of Illustration would become popular, Mr. Fairchild answered, “Yes. It’s In the spirit of the times. Like everything new it seems extravagant and startling at first—Just as Jazz did. That’s why we use It—to startle readers into learning about this Traffic Tydol gasoline. And sales sheets show that we have succeeded.”

Of course, it wasn’t always possible to be so well-prepared:

Willard Fairchild once had to make an advertising layout for clothes made of a certain cloth designed for such places as Palm Beach, Bermuda, Nassau and sunny California. The thing was to be bused on photographs and, owing to the elements of time and expense, the photographs had to be made In the vicinity of New York. In order to give them the real atmosphere, It was decided they must be taken out of doors. Mr. Fairchild gathered his models, four girls and three men, and took them, with the clothes, tennis rackets and golf clubs, to Atlantic City. The layout had to be made and approved around Christmas so as to be ready for the spring exodus to the South. The first three days produced hall and snow, driven by a howling gale.

The third day broke bright and fair —with a temperature of 15 degrees above zero. Mr. Fairchild hustled his models into the 95-degrees-in the-shade outfits, covered them with fur coats, gave them the rackets and golf clubs, tucked them into wheel chairs with blankets around them and took them to the beach. Then he set up the cameras, unwrapped his models and, to keep them from freezing, ran them down on the sand, where they proceeded to register “summer sports.” He says the great difficulty was to get them to stop shivering long enough to make a clear snapshot. The coated and blanketed spectators on the board walk had a grand time. An artist’s model has a great life.

Fairchild was an officer of the Society of Illustrators in the 1930s. In the 1940s, he was the art director for Travel Magazine. In World War 2, Willard joined the USO and went around hospitals, painting portraits of injured soldiers to boost their morale. In 1942, his son, who had enlisted as a pilot in the U.S. Air Force, died in a crash in Fresno, California during training.

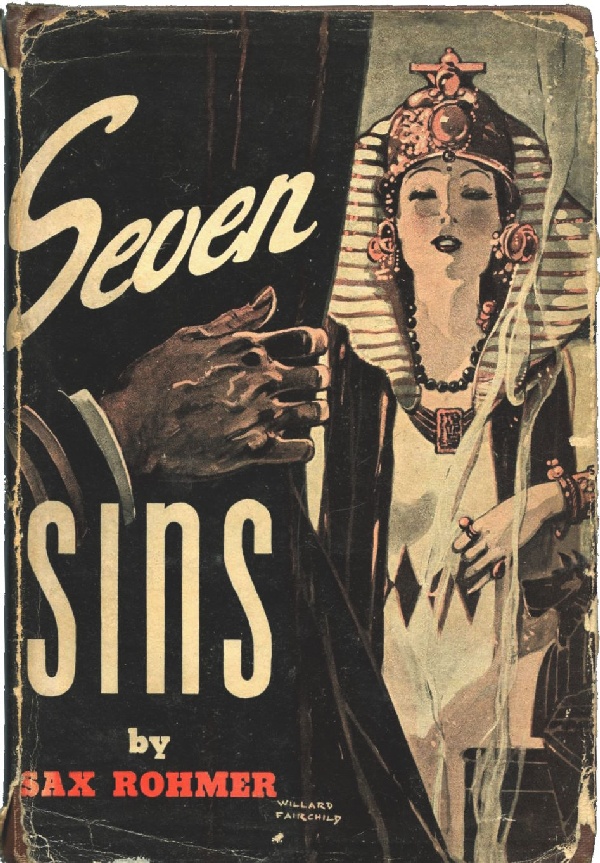

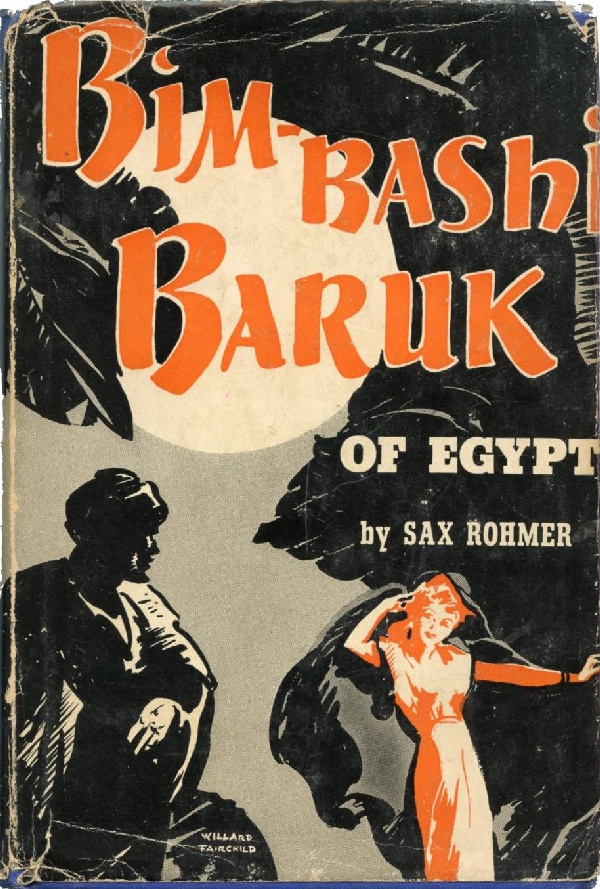

Fairchild did two covers for Sax Rohmer novels: Seven Sins (1943) and Bim-Bashi Baruk (1944). And that’s the last I know of him before his death on June 4, 1946 in New York.