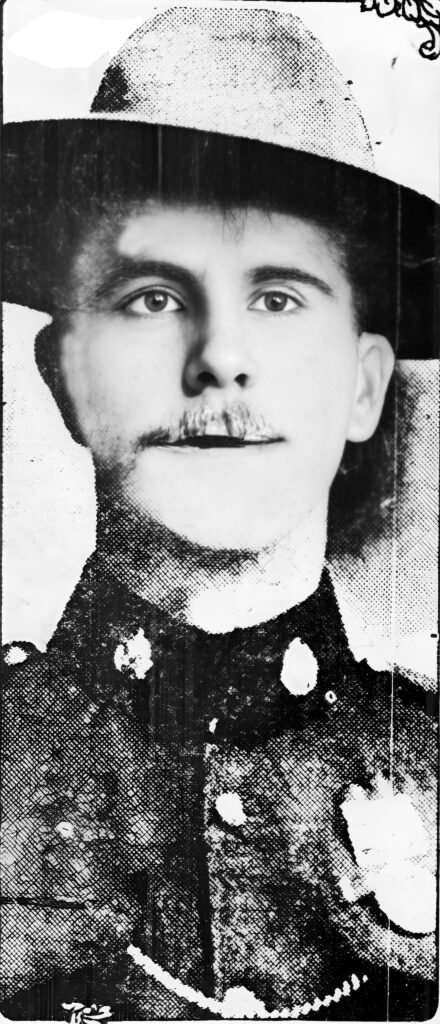

Ralph S. Kendall was an Englishman who became a member of the RCMP, a Mountie as they were called then.

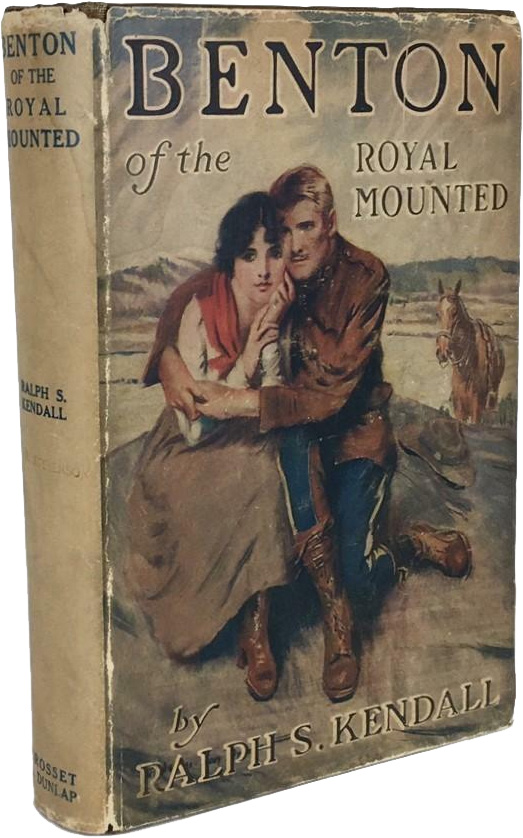

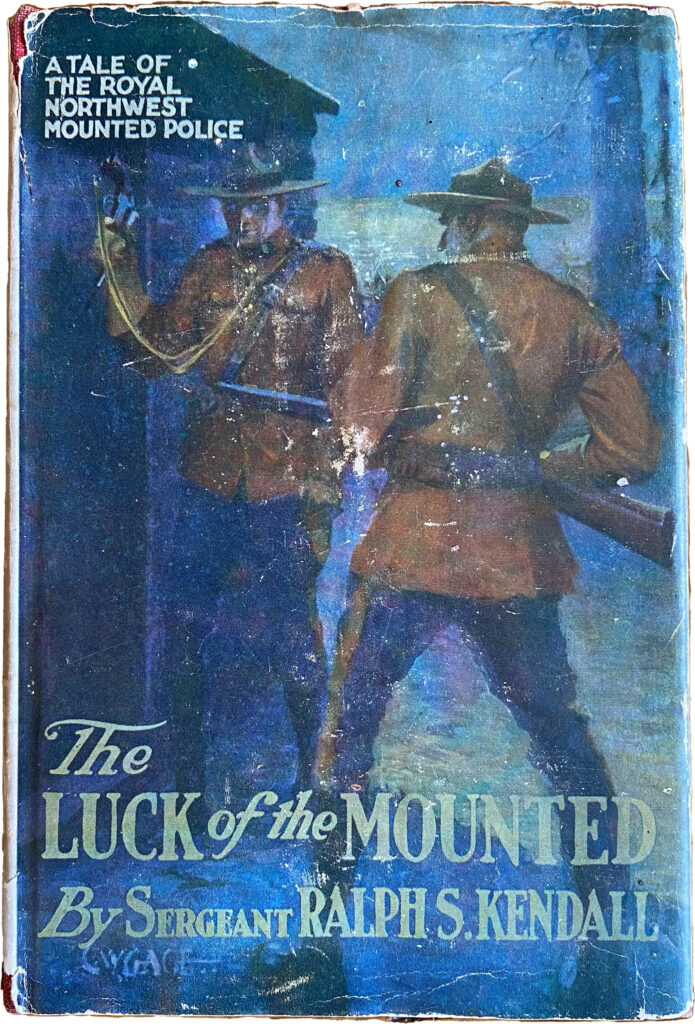

After a long career, he wrote two novels partly based on his experiences: Benton of the Royal Mounted and its sequel, The Luck of the Mounted.

His hero, Benton, was the younger son of a titled British army officer who ran away from home and a step-mother. He came to the United States and drifted west, finding employment on a ranch, where his grit and the ability to hit hard with either fist won him the respect and liking of his fellow cow punchers. A few years later a street fight in Butte led to his becoming a pugilist, and as such he won a big reputation. He fought one fight in Madison Square Garden, spent his money in dissipation, and finally quit because-the game was crooked.

Next Benton went to South Africa and became a member of the Royal Constabulary there. At the outbreak of the Boer war he enlisted and fought in several of the more important battles. Honorably discharged, he wandered to the Canadian Northwest.

Both novels were successful commercially; Kendall was a local celebrity. He wrote this article about his writing career; it appeared in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix in 1919.

The Confessions of a Calgary Writer

BY SERGEANT RALPH S. KENDALL

“Let each man keep to his work, and know how good it is to do that work as well as it can be done.”

John Palmer’s Appreciation of Kipling

This dictum, or, to give it a legal twist, “words to that effect,” was the only sympathy I got when, in an unguarded moment, I confided to an old friend of mine my intention of trying to write an R.N.W.M. police novel. He, like myself, is an old ex-member of the force, A corporeality, be it understood—no mythical prototype of Mrs. Harris. With the jeering familiarity of old comradeship we had been arguing, pro and con, over the merits of a (then) comparatively recent literary production, compiled by another ex-member of the force, a far better man than either of us. it was a mounted police record of many years of faithful service. My old friend, whom I will style B—, apparently wasn’t struck with my idea at all, and, in language more forcible than polite, said so.

“And now.” said he, disgustedly, “You’ve got the gall to tell me you’re goin’ to start in tryin’ to sling ink at the poor old force too?…. Isn’t it enough to have done your duty years back in the outfit without tryin’ to make a dime novel out of it this late along.”

He waxed facetious. “What are you goin’ to do? string a lots of—old crime-report together—all beginnin’. “Sir, I ’ave the honor to report,” etc., an’ all endin’ “I ’ave the honor to be, sir,” an’ the rest of it, with a missin’ link connecting each one up with the other? No! Mr. Bloomin’ “Jarge” (my barrack-room patronymic) it can’t be done, old thing, it can’t be done”. Why! you’re doin’ mounted police work right now, and if you’ll take my advice you’ll just keep your mind on that and evict that writin’ bug from your concrete dome.”

With (to me) heartless point and fluency he said quite a lot of other things, which would not allow of reproduction here.

“Aye!” he rambled on, bitterly, “it’s all very well for you to quote Kipling’s ‘Shall Draw the ’Thing as He Sees it for the God of Things as They Are!’ You’re not Kipling, my boy! —not even a poor relation of his. What publisher would ever take your stuff?”

Warming to his pet antipathy, he continued, ‘Take many of the farcical R.N.W.M.P. novels— concocted obviously by transient civilian authors—men who never served in the force—possess no actual inside knowledge of its regimental routine or the real kind of men it’s mostly composed of—‘Duke’s son—cook’s son—,’ etc., and what do they give you as a substitute?—a bunch of mounted theatrical swashbucklers who’d be in the coop half their time if they made one-quarter of the rotten breaks in real life that they’re represented doin’ in fiction—an’ the ‘ero—” he paused in his vehement harangue to regain his breath—“The ‘ero—constantly portrayed against a heroic background. never makin’ mistakes, arrestin’ or stayin’ the bad man without ever gettin’ a bloomin’ scratch himself—an’ live—mustn’t forget that—plays a very prominent part. Oh, gollops of it, yum, yum,!”

He grinned hatefully. “Percy meets Gladys. Percy rescues Gladys from some ‘road-agents.’ Percy saves Gladys when her horse was bolting with her over the cut-bank. When she recovers Percy Inakes be-ewtiful love to Gladys. Percy finally gets a commission after a few months service. A whole lot of ‘eroic ,’ap-penings, much unctuous repetition of esprit de corps, farcical inquests an’ trials, an’ the creation of what we know to be—utterly impossible situations—legally an regimentally. That’s what you’ll be required to write. Jarge, if ever you want your manuscript to be accepted!”

With perfectly benevolent intention, he now felt he had done all the harm he could to my idea. He was. therefore, so pleased to have his grumble out on this subject that it was with quite a contented sigh that he girded up his loins for departure. Arriving at the safety-zone of the open door he turned on his heel, and, leering at me in horrible fashion fired this Parthian shot “You’ll be the ’ero I suppose?”

However, I clung to my original intention. and finally completed the manuscript of the first R.N.W.M. police novel. “Benton of the Royal Mounted.” it took me over twelve months to do this. I am a mounted police sergeant, and, as the arduous nature of that duty keeps me in the saddle, or at court, etc., ten hours daily, my novel was written mostly between nine p.m. and daylight next morning.

Two years later found me wearily acquiescing in B—’s ill-omened prediction. This, and various other retarding influences, might well have discouraged a more optimistic man than myself. “‘One publisher would, courteously but firmly reply. “Your manuscript seems to be a spirited narrative full of interesting material, and, no doubt, reflecting accurately the conditions under which tbs mounted police work. But. what the public want is this.” etc.

And another gentleman would suggest the exact opposite. Their respective ideas differing so strangely, between them my mind was reduced to one glorious chaos of uncertainty. All of them, however, suggested considerable revision. One critic slated me very severely. Said he, “At many points he lapses into excessive profanity. He seems to delight in alcoholism and bad language.” Realising later though, that, perhaps after all, this last was only a well-deserved and probably well-meant “slap on the wrist,” I began to sit up and con things over a bit. “Jarge!” said I, to myself, “perhaps, intending only to be consistent with realism, you have overdone things a little. Besides—it’s bad literary form—it’s not done—in polite society. You’re not back in old E Division barracks now, you must emasculate some, Jarge— and revise!” I did so.

To cut a long story short, it was finally accepted by a publishing firm of indubitable standing—Tho John Lane Company, of New York, who were kind enough to characterise it as “the real stuff.” Today, the public’s appreciation of it is apparent by the fact that “Benton” has run into many editions.

At the request of the same publishing firm, I am, in whatever few hours I can spare off duty, writing another and similar class of novel, dealing with old days in the R.N.W.M. police. I hope to complete it some time during the coming winter months, when I have a little more leisure for such a task. When it appears I trust that the reading public will extend to it the same kindly patronage and appreciation that greeted the advent of “Benton.”

Why literary ambition should appeal, (as B— put it.) “this late along” to one following a decidedly unimaginative and unsentimental calling is something hard to explain. An Englishman, forty-two years of age, I have led more or less of a roustabout life since I was thirteen. Office boy, iron-worker’s apprentice, dockyard blacksmith, ship’s fireman on boats running between Southampton, the Canary Isles, and the east coast of Africa, irregular soldier during the South African war, cow-puncher, and finally, a mounted police sergeant in appearance I—well .. harkening back to the discussion between B— and myself, recorded in the beginning of this article, amongst the many offensive personal remark: he saw fit to unburden himself of, I remember this one in particular. “Jarge, if your brains only matched your muscles, height an’ build, you’d be a great man.”

When off duty—with my mind (relaxed from the essentially practical nature of my calling—I am, in a crude way, I suppose, a bit of a dreamer. Home materialists might aver that in this work-a-day world is but the idle fancy of a tired or lazy man to regard seriously such poems as Robert Service’s “Dreams Are Best.” I don’t know… Though often having good reason to feel tired, I have no time to be lazy, and yet the following lines always appealed to me:

O you Dreamers, proud and pure,

You have gleamed the sweet of

Life!

Golden truths that shall endure

Over pain and doubt and strife.

I would rather be a fool

Living in my Paradise.

Than the leader of a school.

Sadly sane and weary-wise.

Oftimes, as I sit writing and dreaming far into the nights, beloved old faces, stirring incidents and happy memories flit continually across my retrospective mind-screen. In such reveries—when a man writes with heart, as well as brain—he is no doubt apt to lapse into garrulity and pen much that the reading public would have no part or sympathy in. This is a bad habit of mine, I am afraid, as it generally caused considerable waste of time in revision later.

And. as my mind reverts to the years that were—long before the advent of real estate and oil booms, prohibition, radical labor problems, etc.—the fact impresses itself upon me—what a much more real friendly, contented, and jovial community one found in the west, in those days. But—”The old order changeth”. Comparisons are odious, and grumbling gets one nowhere. As the first pioneers of the west, the R.N.W.M. Police were mainly responsible for the promotion of the genuine friendly spirit amongst all classes that settled later in the Territories. They extended to all the game helpful, guiding, and protecting hand. And the Indian got as square a deal as the white man, in return the civilian population placed in the forces their abiding trust, respect, and personal safety, from the highest to the lowest—rancher, storekeeper, miner, laborer, saloonkeeper—and, even politician. Rarely was that same simple faith misplaced either.

And — it exists today, notwithstanding the fact that the R. N. W. M. Police is at present engaged upon an intricate class of work, which is entirely different, and perhaps—not quite so congenial to them as their former duty. Good men “take on” (enlist) and serve their time. Some re-engage when their period of service is expired—some quit. But just as good men take their place, and the great work goes on.

Time-abiding on occasion, but always in the end “getting its man”, the force extends an implacable arm of Justice throughout the broad provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, Northward it reaches out to Alaska —beyond Dawson City, in the Klondyke—beyond the mouth of the great Mackenzie river, away out into the Arctic Circle to Herschell Island, its most northerly post.

Aye! and again beyond that even—when occasion demands, in view of this latter fact the oft-quoted vaunt of the desperate seal poacher. Reuben Paine. “There’s never a law of God or man runs north of Fifty-Three” would seem more poetical than correct.