Last week, we saw how Black Mask started and how the first editor, Florence May Osborne, left after two years with the magazine. This week we’ll take a look at one of the issues she edited (August 1922) and see what the quality of the magazine was.

The issue we’re reviewing is one issue before Osborne left. I reviewed it from an online scan at the Internet Archive, where you can do everything with a pulp except fondle and smell it. Which was a good idea, considering the age of this issue, any fondling might have reduced it to a pile of…pulp flakes.

Art

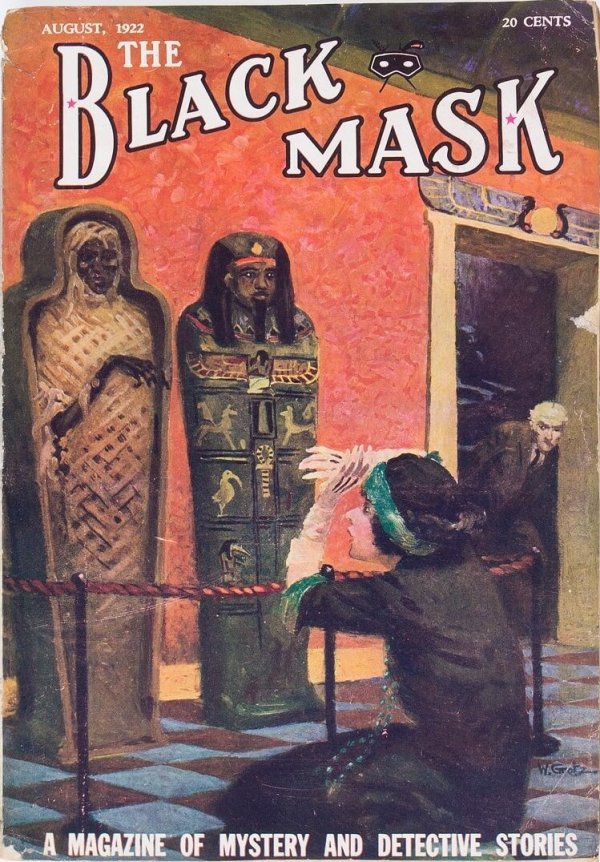

The cover has a woman on her knees, holding her hands up defensively in front of two Egyptian mummy cases, one open. A man is looking on from a doorway. The contents bear no relation to the cover.

The artist is William Grotz (1877-1956), New Jersey illustrator who did the cover for the first issue and many more after that in the early years. A small hint to the real contents of the magazine is a subhead at the bottom of the cover proclaiming this “A MAGAZINE OF MYSTERY AND DETECTIVE STORIES”. Only the title story is illustrated; it’s almost like a book with a frontispiece than a pulp magazine.

The Competition

There are 128 pages in this issue. Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine (DSM) was offering 144 pages for the same 15 cent price. DSM issues came out weekly and the magazine used serials to drive repeat purchases. Black Mask couldn’t use serials because the gap between installments (a month) would be too long for readers to remember.

Mencken in his autobiography, My life as an author and editor, says: “… F. M. Osborne was put in as editor toward the end of 1920, and Nathan and I began to collect $50 a week for supervising her. Unhappily. she was incompetent, so the job failed as a means of collecting unearned increment, and involved us in a lot of hard work”.

Well, now, if this issue is anything to go by, Mencken was wrong, as he often was.

The Bad

I’ll dispose of the dregs first so you can skip them and save the best for last. Vault by Murray Leinster is disappointing, the trope of the robber turning the tables on a villain who’s robbing the same place fails to surprise or excite. J.S Fletcher’s final instalment of Exterior to the Evidence is full of stilted prose, padded unmercifully. J. J. Stagg in The Explosive Gentleman builds up a portrait of a pretentious egotistical man losing his mind and planning a murder for imagined slights, only to spoil it with a gimmicky middle and ending.

The Failure by Illinois author and movie scriptwriter, Harold Ward, uses the same tired trope of robber encountering another robber and turns it into a morality play. Equally bad is his The Police sometimes guess wrong, an account of a policeman whose stupidity boggles the mind. Ward’s third attempt, this under the pseudonym of Ward Sterling, is The Catspaw. It will puzzle and anger cat-lovers, who will ask what cat can stand its claws and paws being painted without wanting to lick it off. These stories total almost 50 pages.

Average

Carl Clausen’s The Weight of a Feather is a pastiche of the courtroom dramas of Melville Davisson Post, down to addressing his lawyer as colonel after Colonel Braxton, Post’s creation. The method of death and its discovery is ingenious. Murder in Haste by John Baer relies on another stupid policeman, but the murder method is somewhat ingenious and adds another reason to dread the dentist.

The Phantom Check by George Bruce Marquis is an example of American bankers unwillingness to part with money. The method of theft is somewhat plausible. Howard Rockey’s The Mistaken Sacrifice is interesting in parts, especially the ending. If Osborne had edited it tightly, it might have been good. But then she’d have to find a short short to fill the space. That’s about 40 pages of readable stories. Now we come to the

Good Stuff

A Weapon of the Law by Brooklyn law clerk George W. Breuker (1884-1978) delivers what you need in a short story. An unarmed judge confronts an escaped convict whom he sentenced to a decade in prison. Crisp, three pages long.

Lloyd F. Lonergan’s The Monolith Hotel Mystery successively casts suspicion on three people for the murder of a woman in a hotel. The first suspect is the man in whose room she was found; he ran away on finding her corpse. The second is her companion; who is found carrying a blood-stained rug in his attaché case as he walks away from the hotel. The third suspect is her husband, who she ran away from. He had tracked her to the hotel and visited her room. And then a fresh-faced cop who wants to get into the corps of detectives reveals the truth. Or did he? Lonergan was a scriptwriter for the early movie serials and he wrote this story like a movie script, showing a series of scenes as the truth is gradually revealed.

His Thirteenth Wife is cleverly titled. Hubert Raymond Carter builds up a picture of a seemingly innocuous man of modest means seeking domestic comfort. He builds his path to riches on the graves of his wives, all middle-aged women with a small estate and no relatives or friends to dispute their death. Now he’s with wife number thirteen, his last before retiring permanently and living off the proceeds. Thirteen is supposed to be unlucky. Read the story and find out how unlucky, and for whom. Or listen to this free audio version.

Finally we come to the best story in the issue, Thyra Samter Winslow’s Blueberry Pie. It starts with a woman protagonist being shocked on reading the news of the death of a man in New York. He was executed for killing a young woman with whom he was cohabiting.

Winslow paints a damning picture of the man as a criminal with all the evidence against him. And then she puts another canvas around that picture and paints the rest of the scene. You’ll never look at a blueberry pie the same way again.

The Rest

The issue ends with a non-fiction column, The Fingerprint Bureau by J H Taylor. According to Mencken, the New York Post office would not grant second class mailing privileges to an all-fiction magazine, so they got around it this way.

Overall

This issue has 40 pages of good stories. A third good, a third ok and a third bad. Not bad for a rookie editor with a presumably low budget. Let’s look at the competition. Street and Smith’s Detective Story Magazine was the only game in town (Flynn’s was launched in 1924), and it had been on the market for seven years. It had struggled through a couple of years of dime-novel fiction before establishing itself with a set of regular authors and series characters. Was the ratio of good to bad fiction in those early years higher than in this issue of Black Mask?

I don’t think so. Mencken’s judgment was probably clouded by his failure to repeat the magic of his two risqué pulps that were early entrants into an uncrowded market. There’s always a market for porn, even the 99 parts water to 1 part the real thing variety that the Parisienne and Saucy Stories offered. Black Mask, on the other hand, had competition from the first issue.

I had fun reviewing this issue and discovering some good stories. Up next week: Secrets of the Mask, part 3: Sutton (Who?) discovers treasures

I like this cover I guess because I’m a sucker for Mummy films and stories but as so often there is no story with such a scene. Your summary of the issue makes this one sounds kind of interesting but I still prefer the Joe Shaw years especially in the thirties. It’s hard to beat a good hard boiled detective story. One of my favorite beginnings started off, “I kicked the corpse in the head”. Wish I could remember the author and story.

Keep slugging Sai, I’m in for the duration.

Walker, I think if you compare this to what it would be in the 1930s, it’s not the same. But if you look at what Detective Story Magazine was doing in the nineteen teens, this is good stuff. And Blueberry Pie has no detective, but it’s hard-boiled for sure. Try a slice.