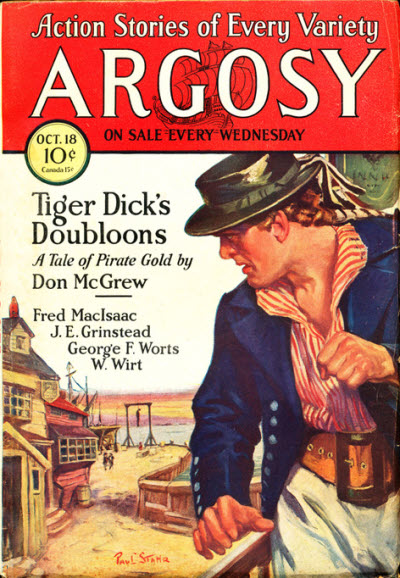

I first came across one of Don McGrew’s stories in The Frontier, a year ago. After reading one, i wanted more. Came across his other pirate story in The Frontier, thanks to Pulpmags.org. It was as good as the first one, and i got interested. Here’s what i found out about him.

|

| Donald Francis McGrew, c. 1930 |

Donald Francis McGrew was born on 19 May 1886 in Huntington, Indiana. His parents were William Henry McGrew and Jennie McGrew (nee Kenower). They were married on 19 August 1885, Don was their first child, and grew up in Illinois, where his five siblings were born.

Indiana is my native State; and though once upon a time I lived in Bagdad-on-the-Hudson and tried to hide the earmarks behind a cane, spats and a Homburg hat, some butter and egg waif from Logansport, Fort Wayne, or Hagerstown would invariably pierce through my disguise, to the Hoosier core of me, and call upon me, as a fellow lodge member, in moments of distress. The Hoosier stamp is always recognizable. In my peregrinations over the seven seas I have never been able to fool any one of discernment: once a Hoosier, always a Hoosier.

I have already told you that the “majority” of me is Scotch-Irish and something of those hard-headed forerunners of mine who “gang awa in the ships to look for gault in the new country.” Ohio and Indiana took them to their early arms, and they thrived, not being adventurous to any extent; but, intermingling with that cold blood, came a distant tiny strain of Spanish on my father’s mother’s side, which, coming to me, cropped out in those “whispers in the night” I have told you of. So when I was twelve I ran away from home, getting only a hundred miles the first attempt, it is true, but instilling a large dose of the “wanderlust” that has never diminished.

My activities? A soldier in the regular cavalry, in Mindanao—Mexican Border service in the Second Maine Infantry — a dispensable lieutenant commanding a one pound gun platoon with the 103d Infantry, 26th Division, in France—newspaper experience from reporter to managing editor—a young cub who, at the age of nineteen, wrote a story in the Philippines, and subsequently sold it to the late Charles Agnew MacLean — that, I think, touches some of the high lights.

He also worked in Minnesota, where he ran a steam shovel in the iron ore district. After this, he worked as a locomotive engineer and fireman.

I have had a look at the world toward the West, having been in Hot Springs when the town was “wide-open”, at Mardi Gras when the wine outrivaled the lights, in Puerto Cortez when lives were sold for a dollar, in Nagasaki where the jin-rickshas and geisha girls are thicker than fleas in New Jersey, and in Chefu with “Jackie Ashore”.

I soldiered in Jefferson Barracks, Walla Walla, Washington; Presidio, San Francisco; Manila, and the island of Mindanao; and have been in Honolulu, Guam, the South Seas, etc., as well as having been in most Northern States along the Canadian border.

While in the Philippines as a private fighting in the Moro rebellion, he wrote a story based on his army experiences, and sent it to his mother. Several years later, when he visited his parents’ home, his mother suggested submitting it to a magazine. The author demurred. Eventually it found its way to New York. When the Tom-Tom Calls was his first published story, appearing in the Popular Magazine, November 15, 1911.

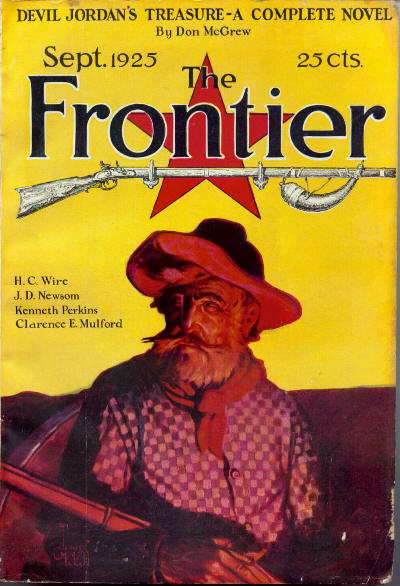

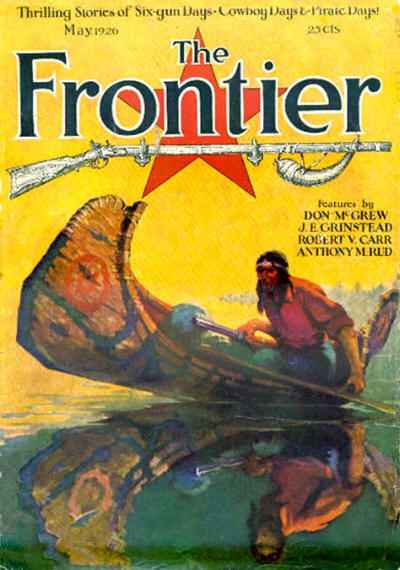

From 1911 to 1917, McGrew published 58 stories in the magazines, a little more than three-fourths of his total output. His stories were being published in the general fiction magazines with the highest circulation – Adventure, Argosy, Short Stories and The Popular Magazine. His story, Chiquita of the Legion (Adventure, October 1915), was one of the earliest French Foreign Legion stories to appear in the pulps. From 1918 to 1924, he didn’t publish a single story. In 1925, he resumed his writing and placed two stories in The Frontier. Devil Jordan’s Treasure appeared in September 1925 and The Devil’s Caldron in May 1926.

Successful as he has been in writing, Mr. McGrew confesses to an inability to spell or to learn the rules of rhetoric. He says a man’s brain is like a muscle, to be developed along any line you choose, and he never chose rhetoric as worthwhile “monkeying” with. As soon as he opened the book to study he got sleepy, or began to think of football or the like. So his teacher marveled at his essays — not because they were marvelous essays, but because they were marvelous in comparison with his knowledge of rhetoric. His sentences were constructed well enough, and he knew when any one made a mistake, but he could never tell why it was a mistake. So now, when a description interests him, he “digs” right into it, as he did then, letting the rhetoric rules take care of themselves. For, as he says, he hates to stop and look into a dictionary when the “spirit” is moving him, and when he is through with the story he has generally forgotten which words he was doubtful about.

I read over again, about once a year, such stories as “Huckleberry Finn”, “Treasure Island”, “Septimus”, “The Virginian”, “The Beloved Vagabond”, and “Lord Jim” — not to speak of Conrad’s other works, and Kipling’s tales of the inimitable Mulvaney.

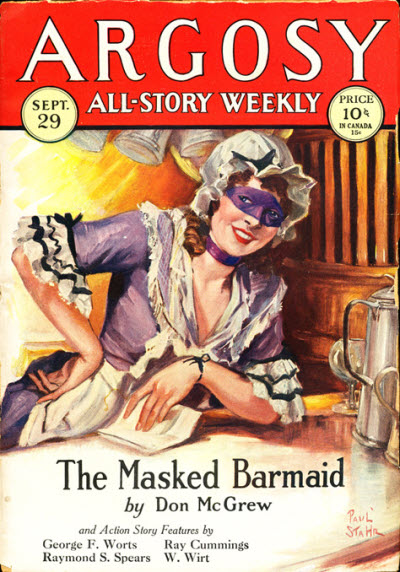

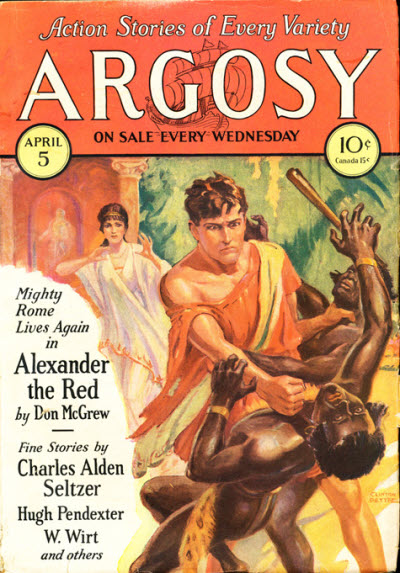

After 1926, his stories appeared in The Popular Magazine, Argosy and Short Stories. His last published story, The Meeting of the Twain, appeared in 1934 in Short Stories.

|

|

In between writing, McGrew found the time to marry 5 times, maybe 6 – and have at least 5 children. Definitely a writer who sought out adventures of all kinds. After 1930, he moved further west, and entered politics as publicity director for Gov. Culbert L. Olson. Though the campaign was successful, McGrew didn’t get paid, and he sued for $1500.

During World War 2, he tried to get the US government to invest in opening some tin mines in California, but failed. He died in July 1955, having committed suicide in his cabin in Orleans, California.