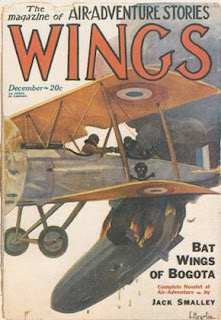

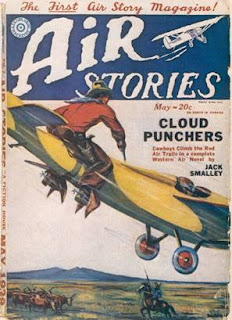

When Charles Lindbergh flew the Atlantic in 1927 the publishers rushed into print with tales of flying adventures. Jack Kelly, publisher of Fiction House which included such pulps as Lariat, Action Stories and Northwest Stories, launched Air Stories and Wings in such a hurry that he wired me to write a novelet over the weekend and wire him the title so he could make cover plates. He had been featuring my Western stories, but a true pulpeteer can write about anything. All he needs is a glance into a reference book or a copy of National Geographic for local color.

None of the publishers cared if the staff contributed to rival magazines. Billy Fawcett paid his staff one cent per word, on the undeniable assumption that fellow editors would be influenced to buy. A rejected manuscript could be sold elsewhere, so we usually rejected each other’s stories and got two cents a word from other publishers. I used the name “John Winburn” on stories I sold to Fawcett.

Even second and third string writers did well in those days. My salary as managing editor was $750 per month plus bonuses, Fiction House paid me $1, 000 for serials of 50, 000 words in five installments, and I was also writing stories for Triple-X, Adventure, Short Stories, Argosy, Liberty, Lariat and many others. The motto of the flapper age was “spend it,” yet we still found money to put into the zooming stock market. As we added more and more magazines to the Fawcett list and the staff grew until we moved into a large building in Minneapolis, it seemed as though the world of the pulps would live forever, and forever shower down gold.

Times were so prosperous that Roscoe Fawcett decided we should move into the upper crust of the slick women’s magazines, such as McClure’s or the Ladies’ Home Journal, and change True Confessions to Fawcett’s Magazine. I had become editor of Triple-X and didn’t pay much attention to the plan. I sympathized with Roscoe, who had left the elite corps of the air force and his comrades to find himself involved with junk magazines, filled with thinly veiled ads for contraceptives, cures for gland disorders, and porno marriage manuals.

Fawcett’s Magazine hit the stands with a dull thud. Although it contained articles and stories by leading slick-paper writers, nobody bought.

Even Whiz Bang profits could not make up the losses. We were still in the Robbinsdale offices, and all of us could see the glum faces of the creditors from the printing, engraving and paper companies as they climbed wearily up the stairs enveloped in an atmosphere of doom. When I was called into the front office I expected to be fired along with most of the staff of Fawcett’s.

I was told that Fawcett’s was being discontinued and we would have to cut staff and expenses to the bone. Asked for suggestions, I proposed that Fawcett’s be changed back to True Confessions and to fill the magazine with stories of sex.

“I don’t care what you do with it,” said Roscoe with disgust. “I don’t want to know about it.”

“We haven’t the money to buy manuscripts,” said Billy. “But go ahead. I’m making you assistant managing editor.”

I had sold one of these first- person love stories to Smart Set, titled “A Model of Virtue.” All you needed to sell a story to the pulps was a good title and an arresting lead paragraph. I can still remember my opening sentence for “A Model of Virtue”: “The first time I posed in the nude I fainted and almost spoiled everything.” I decided to write the stories for the revived True Confessions. But what to do for the photographic illustrations?

I hurried downtown to Finkelstein & Rubin, a distributor of motion pictures for the Midwest, and said I wanted to buy some old stills used to advertise films. I was sent to their ad layout man, A1 Allard. We went through hundreds of photos from dusty files, most of them long forgotten. From these I picked enough illustrations for the stories.

Working at top speed, I ground out stories to fit the stills. The printer and paper house had agreed to extend credit. With sexy titles on the cover and stories to match, True Confessions was revived and soon selling a quarter million copies. I was given the full title of managing editor and a raise; life among the pulps was good again.

|

| True Confessions, April 1926 – First issue after the change in title from Fawcett’s Magazine |

I was looking for someone to replace me on True Confessions when a tall young woman climbed the stairs and told me she wanted to become a magazine editor. Her name, she said, was Hazel Berge and she was a schoolteacher in a small Minnesota town; she felt that life held more excitement than teaching. Something told me to hire this totally inexperienced editor on the spot. In a few months she was the entire staff of True Confessions, except for one secretary, and had a number of steady writers in her stable.

Hazel established an advice to the lovelorn department, “Dear Priscilla.” One day Priscilla arrived from Des Moines, where she had been employed in the society department of the Des Moines Tribune. “I wish to establish that any letters sent to my department belong to me,” said Priscilla. Hazel and I agreed, wondering what was coming. She showed us a sheaf of ruled notebook paper, covered with fine script written in green ink. “It’s an answer to one of my departments in which we posed the problem of a needy young mother who was urged by a rich friend to give her daughter to her for adoption. Here are about ten pages telling why the poor mother should keep her daughter. It’s signed G. Bernard Shaw.”

Love, said Shaw, was the most important thing in life.

“You can have it, Priscilla,” said Hazel. “Send me a copy and we’ll use what we have room for.” I wondered what a collector would pay for an original Shaw manuscript. After Priscilla had left, I told Hazel that her secretary seemed unaware of the value of a Shaw original, and probably never read anything of Shaw’s.

“That’s why I like her,” said Hazel, in that calm, even voice of hers. “She’s exactly like my readers. They never heard of Shaw, either.”

In later years, after I left Fawcett’s, Hazel went to New York and became editor of Photoplay and later of Dell’s romance magazines.

We had begun to add movie magazines—eventually Fawcett’s provided five movie magazines in the golden age of picture shows—plus a do-it- yourself magazine I named Modern Mechanix, and Startling Detective Adventures, a true detective magazine of actual cases. We were bustling along, and Billy took his wife Annette to Europe. Roscoe and I went to Louisville to see the manager of the C. T. Dearing Printing Company, which held large contracts with us, and later we stopped at French Lick to get in some golf. At the end of nine holes Roscoe said that he didn’t feel well. We went back to the hotel and Roscoe tried the mineral waters but, like all other cures, the waters gave him no relief. He went to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester and was operated on for cancer.

Although Roscoe had given me full rein editorially as managing editor, I now found myself also assistant general manager and completely responsible for the company. Billy cabled from Paris the description of a magazine I was to launch at once, to be named Mystic Magazine. The collapse of the stock market had caused great uncertainty, but Billy was optimistic. Annette had been to a fortune-teller and was convinced that women were eager to have their horoscopes read, the future predicted, the spirit world investigated and loved ones communicated with through mediums.

|

| Mystic Magazine issue |

I dropped everything and flew to New York, and at the offices of the American Society for Psychical Research I was fortunate in finding a young writer named R. T. M. Scott II. I soon had him settled in a house and we rushed into print with everything we could assemble in fortune telling, ESP, astrology, handwriting, sorcery, witchcraft, palmistry, crystal balls and even an exclusive message from A. Conan Doyle in the spirit world. The author of Sherlock Holmes had promised to communicate, and Mystic Magazine was happy to get an exclusive. I put a reasonable amount of sex on the cover (“Is Your Sweetheart True?”), scantily-clad nymphs inside, and even a message from Rudy Valentino, but to no avail. Mystic laid an egg. Those who had twenty-five cents to spend were thinking in terms of a plate of beans and a cup of coffee.

Annette’s fortune-teller was wrong. Dead wrong.

It seemed to me that the pulps were showing signs of aging.

Styles were changing, too.

Destry Rides Again, published as “Twelve Peers” in Western Story in 1929 under one of Frederick Faust’s many pen names, was a well constructed story of character, in which the hero grows tired of violence and vengeance and puts away his gun while his enemies are allowed to escape.

Samuel Dashiell Hammett, writing the goriest pulp stories that ever appeared in Black Mask, had always been a master of violence and death. “The Dain Curse” had the streets running in blood. Dash got so pressed for some other way of saying that the gun blazed, he invented some neat substitutes, such as “a bullet kissed a hole in the doorframe,” or “the machine gun settled down to the business of grinding out metal like the busy little death factory it was.” Hammett had strung together several stories around the same characters and the same setting for what became three books; but in “The Maltese Falcon” he conformed to the standard pulp serial of five installments, 10, 000 words each. It started in the September 1929 issue of Black Mask Magazine and concluded in January 1930. You could see that he was now building around characters rather than bullets. He and the pulps had grown up. Sam Spade, allowed by Hammett to wear his own first name, created a new breed and a new realism that had outgrown the pulp magazines. His last long story, “The Thin Man,” was sold to Redbook before appearing in hard cover. Five books, seventy-four short stories and novelets, plus the five-part Falcon serial —a small output as pulpeteers go, yet he exerted a tremendous influence on all of us who were writing fiction in those days. Even Hemingway regarded Hammett as the master.

Time was running out for the pulps. In August 1932, I sent a memo to Billy at Breezy Point showing the declining sales of Triple- X and Battle Stories, which were no longer showing a profit. As millions became unemployed, they stopped spending a quarter for a magazine that provided only a few hours of entertainment. Billy approved my decision to kill them off.

|

| Battle Stories April 1932 issue |

Even that giant of the pulps, Western Story, was dying. By 1937 it was able to pay only a half cent a word. They paid Max Brand $112 for a story of 2, 200 words. He turned to Hollywood and soon was making $2, 000 a week, writing complete shooting scripts for his characters, Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespie.

Of all the magazines I wrote for, only Argosy survives. Copies of the magazines are scarce. Pulp paper turns brown and brittle, as if the very substance of the fiction printed on it was doomed to self-destruct and disappear. A few private collections of pulp magazines exist, such as the one given by George Hess to the University of Minnesota where it is preserved for posterity.

Said Professor Harris McClaskey of the university library: “In the past, much of the popular culture of a society disappeared because no one considered it worth saving. Not surprisingly, much of pulp literature never even made it into libraries.”

When I was fired in 1933, I joined the pulpeteers’ migration to Hollywood along with Max Brand and H. Bedford-Jones, for writers were welcome in films. However, Roscoe rehired me to run the five “fan” magazines owned by Fawcett’s, and I took over a floor in the Professional Building on Hollywood Boulevard.

By 1936 even the movie magazines were suffering. Roscoe Fawcett said good-bye to me and went back to Rochester.

My career in magazines was over. Roy Durstine, president of Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, summoned me to New York and hired me to open the advertising agency’s first West Coast office.

It was fun while it lasted.

Dashiell Hammett’s close and dear friend, playwright Lillian Heilman, summed up the pulp story in her memoir, An Unfinished Woman: “I am not clear about this time in Hammett’s life, but it always sounded rather nice and 1920’s Bohemian, and the girl on Pine Street and the other on Grant Street, and the good San Francisco food in cheap restaurants, and dago red wine, and fame in the pulp magazine field, then and maybe now a world of its own.”

That is it exactly. It was a world of its own.