[In which your slow-witted servant recommends to your exaltedness’ attentions the boundless wisdom, lofty morals and incomparable diversions to be found in the stories of the itinerant story-teller Kai-Lung as related by the venerable hermit Ernest Bramah.]

Ernest Bramah set his Kai Lung stories in a China that never was, where people spoke in an archaic, orotund, circumlocutory and mannered way, conveying messages that were diametrically opposed to the words that they actually said. The artistry of the language is a delight, and if you relish subtle verbal humor, you are in for a treat. Here is an example; a leader of labourers is talking to the merchant who employs them, asking for a raise

“Know then, O battener upon our ill-requited skill, how it has come to our knowledge that one who is not of our Brotherhood moves among us and performs an equal task for a less reward. This is our spoken word in consequence: in place of one tael every man among us shall now take two, and he who before has laboured eight gongs to receive it shall henceforth labour four. Furthermore, he who is speaking shall, as their recognized head and authority, always be addressed by the honourable title of ‘Polished,’ and the dog who is not one of us shall be cast forth.”

“My hand itches to reward you in accordance with the inner prompting of a full heart,” replied the merchant, after a well-sustained pause.

Or another merchant who, tallying his profits, is distracted by the wailing of a street musician:

To Wong Pao, the merchant, pleasurably immersed in the calculation of an estimated profit on a junk-load of birds’ nests, sharks’ fins and other seasonable delicacies, there came a distracting interruption occasioned by a wandering poet who sat down within the shade provided by Wong Pao’s ornamental gate in the street outside. As he reclined there he sang ballads of ancient valour, from time to time beating a hollow wooden duck in unison with his voice, so that the charitable should have no excuse for missing the entertainment.

Unable any longer to continue his occupation, Wong Pao struck an iron gong.

“Bear courteous greetings to the accomplished musician outside our gate,” he said to the slave who had appeared, “and convince him—by means of a heavily-weighted club if necessary—that the situation he has taken up is quite unworthy of his incomparable efforts.”

In the Kai Lung stories, there is never a straight path to any point, and there is never a straightforward conversation. Stories wind from one plot twist to another, and conversations take entire pages; but there is never a feeling of slowness because the words are so precisely crafted to amuse. There is plenty of satire and irony in the stories. I could keep on giving quotes from Bramah, but I will leave you to discover them.

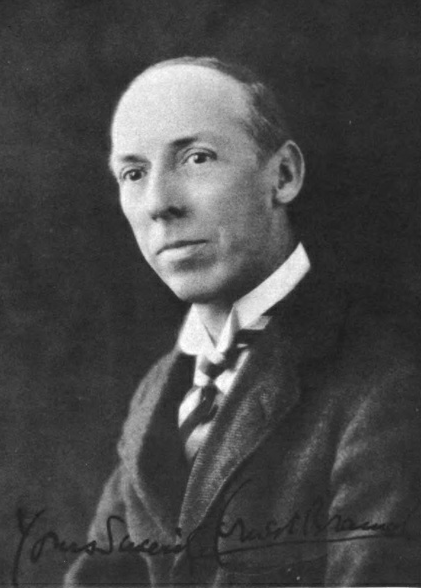

Ernest Bramah (real name: Ernest Brammah Smith) was born on 20 March 1868 in Manchester, the son of Charles Clement and Susannah Brammah Smith. He attended Manchester Grammar School. In 1887 or so, he went to a farm in Erith as a pupil and stayed there for about 15 months, moving to another farm called Tudorlands, where he spent a further nine months. He decided to become a farmer, and spent a year choosing a farm. Then he spent four years running his farm.

His experiences formed the basis of his book, English Farming and why I turned it up (1894), a book that did not sell at all and was remaindered and pulped. In 1890, he started writing a column for the Birmingham News, and with financial support from his father, he was able to travel to London to take up journalism as a career. In 1892, he became a secretary to Jerome K. Jerome, who was then an editor of the London magazine Today. Later he became an editorial assistant for Today. He remained at Today till 1895, when he left to become the editor of the Minister, another magazine.

On 31 December 1897, he married Lucy Maisie Barker in St. Andrew, Holborn, Middlesex. The same year, he had quit his job to become a full-time writer. By July 1899, he had written his first book, The Wallet of Kai Lung, and was searching for a publisher. He was rejected by many publishers before the book reached Grant Richards, who was then living at Bisham Park Farm. E.V. Lucas brought the manuscript to Richards, who liked it. At the time that Richards first received it, the manuscript had only three stories in it. It was expanded to nine stories before being published in 1900. The book did not do particularly well, and till 1907 only two thousand two hundred and fifty copies were printed in three editions.

His work was glowingly reviewed by writers like Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch and Hillaire Belloc, and Bramah started contributing to popular magazines like Punch and The Strand magazine, where his detective, the blind Max Carrados, was appearing at the same time as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Carrados was highly popular with readers, and was a rival of Sherlock Holmes.

In 1907, Bramah produced his first, and only, work of science fiction, What might have been: The story of a social war. The story is set in 1918, when science has made flight with wings possible. A Labour government is in office, with a comfortable majority, thanks to universal suffrage; nationalization and strikes are happening frequently and the British Empire is disintegrating. The middle class, conscious of their fate, are leaderless and have withdrawn from politics. A mysterious savior appears who forms a new party, the Unity League, under which the middle class unite. The League’s members then boycott coal or coal products. This paralyzes the country, civil war breaks out, and the Government resigns. The Unity League forms a government, and returns the country to the status quo, abolishing universal suffrage and undoing the Labor government’s legislation.

In 1914, he published his first collection of Carrados stories, Max Carrados. This was a popular success, and Carrados stories continued to appear in The Strand magazine, rivaling Sherlock Holmes in popularity.

Even though his publisher, Grant Richards, requested him at least twice a year to write more Kai Lung stories, it was only in 1921 that Bramah decided to write more. His second volume of Kai Lung stories, Kai Lung’s Golden Hours, was published in 1922. It was successful, and led to the reprinting of the earlier book, The wallet of Kai Lung. Two more collections of Kai Lung stories appeared, Kai Lung unrolls his mat (1928) and Kai Lung under the Mulberry tree (1940), as well as a novel, The Moon of Much Gladness (1932).

In between these, there were three more Carrados collections, Eyes of Max Carrados (1923), Max Carrados Mysteries (1927) and The Bravo of London (1934).

Ernest Bramah was a very private person, keeping his private life hidden. He did not give any interviews and conducted his business with his publishers through letters, sometimes not seeing them for years at a time. He passed away in Weston-Super-Mare, Somerset on 27 June 1942.