[James Francis Dwyer’s biography reads like a story from the pages of the pulps. He was a mailman, a reformed convict and a tram conductor before he met with success as a writer. He wrote adventure stories for the pulps – stories which are as exciting today as they were when they were written.

One such is the “The Spotted Panther” is a story of three adventurers in a quest for the Great Parong of Buddha, a fabulous valuable sword. To get it they go to the Place of Evil Winds, encounter the Golden One and have many other adventures. It is a fast paced and thrilling pulp adventure, typical of his writing.

He was also a proto-blogger, selling subscriptions to letters of his travels as they happened. Want to know more? Read the article, after the jump.]

James Francis Dwyer was born on 22 April 1874 at Camden Park, New South Wales, Australia. He was the fifth son of Michael Dwyer, farmer, and his wife Margaret, née Mahoney, both from Cork, Ireland. The family moved to Menangle in 1883 and next year to Campbelltown. He and his seven brothers used to work on the family farm. He was educated in local public schools till 14, when he was sent to relatives in Sydney, where he worked as a publisher’s clerk.

He became a letter-carrier at Rockdale, New South Wales, in May 1892. On 7 November 1893 he married Selina Cassandra Stewart. Despite a brief meeting with Robert Louis Stevenson which turned his thoughts towards writing, he remained with the post office, becoming a postal assistant at the Oxford Street branch from 1895.

On June 16, 1899 Dwyer, with two associates, was convicted of forgery to obtain ten pounds and received a seven year prison sentence. His associates got off lightly, with one and two year prison sentences. He was paroled in 1902 after serving nearly three years in Goulburn gaol. While he was in prison, he started writing, publishing a poem and two short stories. As ‘J.F.D.’, ‘Burglar Bill’, ‘D’ and ‘Marat’, he wrote for the Bulletin.

After he was released, he worked as a salesman, clerk, compositor, pigeon-buyer and signwriter. He accidentally met Sir Frederick Darley, the Judge who sentenced him. Sir Frederick took him to his office and gave him a lengthy letter of introduction to “The Sydney Morning Herald.” The letter brought him a polite reception from the management but no job.

He turned to journalism, freelancing for Truth and Sydney Sportsman, making around twenty pounds a week. He was convinced that he could not prosper as a story writer in Australia, and in 1906, after his parole completed, left for London with his wife and daughter, Glory. He had around a dozen stories which he tried to sell, but the magazine market was so slow that his savings evaporated. Lacking a college education, and without any references, he could not get a job. He decided to immigrate to America.

Once he reached New York and got past immigration, he sent the twenty five dollars required to get past immigration back to his wife in London. He was broke and looking for a job, so he went to newspaper offices looking for work as a journalist. He was told to “get to know the town. Get Americanized before you try to get a job” by the editor of The World, who advised him to get a job as a tram conductor.

Dwyer applied for this job. In the meanwhile, he took a job addressing envelopes for a firm in Beekman Street. He got ninety cents a thousand, and would do around 1700 a day, earning him around $ 1.50 a day. He was living in a room costing $ 1.25 a week, eating a pound of rice in three days. He lost this job because he was delayed when he went out to send money to his family.

In the meantime, his wife got worried, and decided to join him. She sold and pawned everything they had, but found herself two pounds short. She managed to borrow the two pounds from a fish merchant in London, and set off for New York. Before she arrived, Dwyer managed to get another job addressing envelopes. He also managed to get a job in opera, paying him fifty cents a night.

The week she arrived, Dwyer managed to get the tram conductor job. He now faced a fresh obstacle, getting his uniform. His wife pawned a lace kerchief to get money for the uniform, and Dwyer joined as a trainee. After three days, he was examined by an inspector, who failed him. Luckily for Dwyer, a drunk discharged conductor came up at this time and started abusing the inspector. The inspector asked Dwyer to fight the conductor. Dwyer did, and in winning the fight, passed the exam.

Dwyer spent about ten weeks as a tram conductor, and wrote a story about how the tram company was endangering passenger safety by ignoring regulations. He sold this story and with his salary, had $ 33 in savings. Out of this money, he bought a typewriter for $ 8. With this, he started writing stories, and in his first year, was earning about $ 20 a week. To support their family, his wife had to work as well, inserting small bones to stiffen woman’s collars, making about $ 5 a week.

|

| James Francis Dwyer and his first wife, with their daughter Glory, c. 1912 |

|

| James Francis Dwyer with his daughter Glory, c. 1912 |

After winning a contest, he received a commission to write for the Black Cat magazine. After that, his stories were published in Harper’s Bazaar, Collier’s, The American Magazine, The Ladies’ Home Journal and other popular magazines and proved very profitable. By 1912, he was making around $ 5000 a year. That was the year he wrote his first novel, “The White Waterfall”, a South Seas adventure story of a scientific voyage to the “Isle of Tears”, and the subsequent mayhem as all goes as unexpected.

To gather information about the locations for his stories, he travelled extensively in America and Europe; and revisited Australia in 1913. His wife got tired of the travel, and wanted to return to Australia, but Dwyer refused. She filed for a divorce in Reno, Nevada. He was divorced in December 1919, and on 30 December, 1919, he married his agent, Catherine (Galbraith) Welch. His ex-wife returned to Australia with their children.

His search for exotic settings and tourist information, and his second wife’s interests as a cultural historian carried them through Europe, Asia and North Africa. In 1920, they established a permanent residence at Pau, in the French Pyrenees.

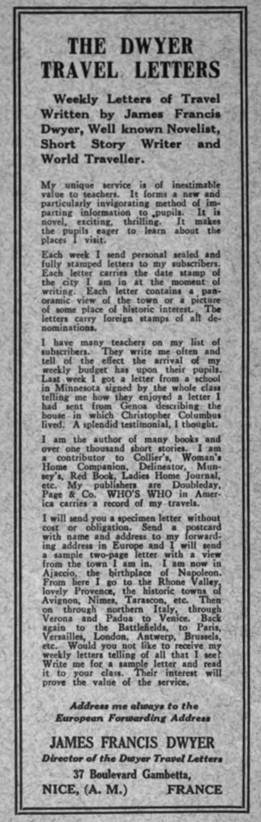

In 1921 they started the Dwyer Travel Letters to inform prospective American tourists about places in Europe. This was a weekly letter from Dwyer to the subscriber, containing a picture and describing the place that Dwyer was currently visiting. Dwyer sold this as a service for teachers and tourists.

When France fell in 1940, the Dwyers had to escape from the Nazis through Portugal and Spain. The Nazis wanted him for the anti-Nazi propaganda articles he had written for British and French newspapers. They lived at Dover, New Hampshire, during World War 2 and returned to Pau in September 1945. In 1949 he published his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings (published only in Australia, not in the US and UK), which he wanted to be an inspiration to young authors and a protest against judges who created second time criminals by passing harsh sentences.

James Francis Dwyer died in Pau, France on 11 November 1952.

Link to the only book of his in print below:

You are right, this very interesting biography reads like something from the pulps. Hard to believe he was sentenced to 7 years in prison for forgery involving 10 pounds.

My favorite Dwyer stories are the two serials that he did for BLUE BOOK in the mid-thirties. I also have one of the Flanagan illustrations used for one of the serials.

Yes, it does seem harsh. Even though ten pounds then would be worth about a thousand pounds ($ 1500 or so) today.

Care to share the illustration? If you send me a scan, I'll post it here.

Excellent blog about Dwyer, I have not read anything by him, but love that South Sea Adventure stuff. I like Beatrice Grimshaw's tales of the South Sea's from Everybody's, great stuff! As For Richard Flanagan a fellow Aussie he was awesome as a pen and ink man, would love to have an original from him….

I find the man fascinating. I have more than 40 of his travel letters and the stamped envelopes and postcards that came with them. His writing is so insightful and enthusiastic. I also have the final letter where as he went to see his dying mother he closed down the travel letter business and returned unused subscription funds. This is the best biographical account of his life I have read yet.

Hi Christopher,

I'm glad you liked this post – Dwyer's life was quite fascinating. His fiction was quite good too, I just got hold of a serial, Caravan Treasure, that he did in Blue Book magazine, and it's very enjoyable.

If you would care to share some of the letters, you can reach me via email at pulpflakes AT gmail DOT com.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Christopher – if you are ever looking to get rid of any of these items, please let me know. James Francis Dwyer is my great-great-grandfather, and my mother collects anything she can connected to the family

Hi Emily,

Glad to have you visiting here. It would be wonderful if you could share any other memorabilia about James Francis Dwyer. You can reach the blog at pulpflakes AT Gmail DOT com.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.