I recently read this issue of Blue Book. It’s the very first issue under the Blue Book title, under which name it would remain in monthly publication for more than 49 years. It’s scarce; I haven’t seen a copy for sale in a dozen years. Blue Book is underrated despite being one of the Big 5 general fiction pulps; Argosy, The Popular Magazine, Adventure and Short Stories are the others. This issue is a milestone in the magazine’s history and a great example of the early stages of pulp magazines. As such, it’s worth a deeper look.

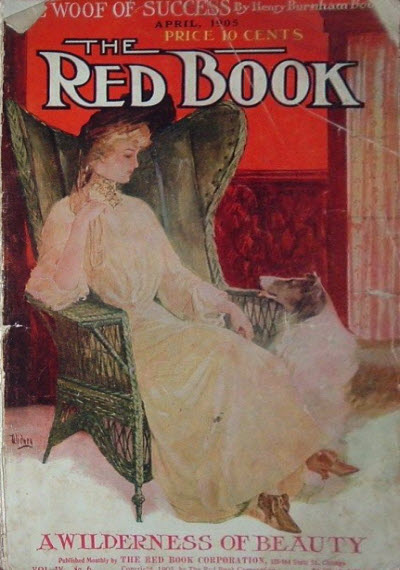

Blue Book was a sister title of Red Book. Red Book was the first major all-fiction magazine published out of Chicago and had built up a circulation of ~340,000 by the June 1906 issue, with the publishers claiming no more than 5% returns on each issue. It was such a success that Street & Smith started Smith’s Magazine in April 1905, sporting similar cover designs and fiction content.

There were enough submitted stories that were printable but not suitable for Red Book that the publishers thought of starting another all-fiction periodical. This they did in May 1905, calling it the Monthly Story Magazine. Dime novel regular W. Bert Foster had a story in the first issue, and the editor was Trumbull White, the editor of Red Book. White remained the editor for till September 1906, when Karl Edwin Harriman took over. Maybe as a result of the editorial change, Blue Book‘s covers markedly improved starting January 1907.

September 1906

January 1907

When this issue was published, its competitors were few in number, and they weren’t called pulps. They were the rough paper magazines. There was no stigma attached to them, and they offered more variety to readers and freedom to contributors than regular magazines. The magazines were

| Title | Publisher | Date | Circulation | Comments |

| All-Story | Frank A. Munsey | Jan 1905 | Undisclosed | |

| Argosy | Frank A. Munsey | October 1896 | 413,000 | Impressive for a monthly magazine, which Argosy was at the time. For comparison, the Saturday Evening Post was selling ~700,000 copies weekly. |

| Scrap Book | Frank. A Munsey | March 1906 | Undisclosed | |

| Red Book | Story-Press Corp., Chicago | May 1903 | ~340,000 | Printed on white paper stock, but content was all-fiction and format was pulp-like. |

| Ainslee’s | Street & Smith | October 1902 | ~250,000 | Was printed on white paper stock, but content was all-fiction and format was just like a pulp. |

| Popular Magazine | Street & Smith | November 1903 | ~265,000 | |

| Smith’s Magazine | Street & Smith | April 1905 | Undisclosed | Pulp from the beginning |

| 10 Story Book | Daily Story Publishing Co., Chicago | Pulp from 1903, probably earlier | ~65,000 | Under the counter mag with nude photos. , used pulp grade paper. |

| Young’s Magazine | Courtland H. Young | Pulp from 1906, probably earlier | Undisclosed |

I may have missed some titles but not prominent ones. Cavalier, Short Stories, and Adventure came later.

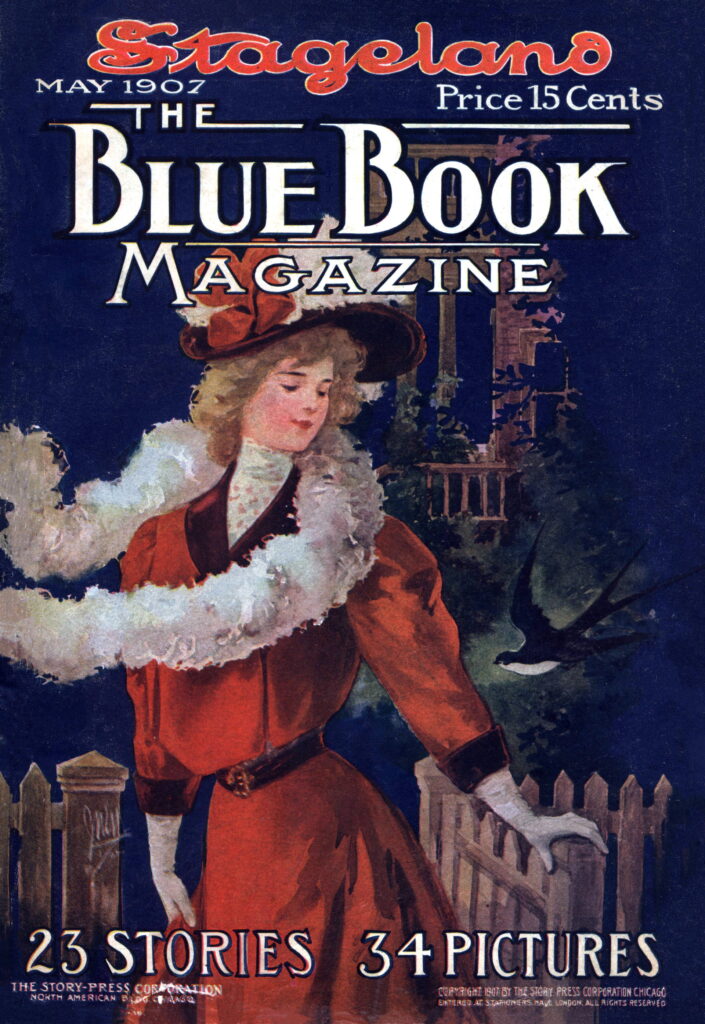

The issue itself is a hefty 224 pages of content combined with 16 pages of advertising, including the front and back covers. The cover features a young lady wearing a fur stole, by the artist <TBD>. You could safely take her or the magazine home to meet mother. Ainslee’s, Red Book, Smith’s Magazine and Young’s Magazine all featured similar covers, appealing to both men and women. The cover is reproduced inside in color, with a dedication to the newsdealers of America.

Following this is an editorial, pronouncing the magazine a success and printing letters of praise from readers and newsdealers. The letters themselves are less interesting than where and who they’re from. The readership is exclusively in the Midwest, South and East Coast. This is not surprising considering the magazine’s offices were in Chicago, Boston and NY.

Also of interest is the editorial announcement of the addition of story headings. These refer to the pictures accompanying each story; there are six illustrations in this issue for almost twenty-four stories. A low number, explainable by the reason that Red Book too had difficulty getting enough illustrators in and around Chicago to work with them. Using artists from New York to produce a magazine in the days before email would have been uneconomical, even assuming the communication difficulties could be overcome. Blue Book would add more illustrations as time went on, often using multiple illustrations for the same story, becoming one of the most profusely illustrated pulps. There is no sign of that in this issue.

There are twenty-three stories, ranging from a thousand words in length to about fifteen thousand words. They are calculated to appeal to both men and women, with six love/romance, five crime/detective stories, seven stories with O’Henry style twist in the tale endings and one story that features a life-prolonging potion.

I found four stories interesting. The Will and the Man by M. M’Donnell Bodkin is a refreshing take on that popular Victorian theme, an attractive heiress who is the prey of a fortune hunting man. It features a fake will, a nurse with a heart of gold and a Perry Mason like lawyer hero who is willing to break the law to provide a happy ending. Bodkin, an Irish lawyer, was the creator of the first detective family in modern fiction.

A Self-Inflicted Vengeance has fantastic elements; it’s the story of a man who inherits a life-prolonging potion from his father, only to find that it is a mixed blessing. The author, Gilbert P. Coleman, was an English instructor at Annapolis who also co-authored a popular college novel, Brown of Harvard.

Mysteries of the Rail #1: The Car That Vanished is a uncredited reprint of Victor L. Whitechurch’s Sir Gilbert Murrell’s Picture that appeared in the British periodical The Royal Magazine in October 1905. It is said to be one of a series edited by Marvin Dana. This is probably a ruse to shine in reflected glory; Dana was already a popular author in the US while Whitechurch was unknown. The editing is minor, confined to one superfluous paragraph at the beginning outlining the character of Thorpe Hazell, the vegetarian health nut railway detective who is the hero of the series.

The Skull With the Diamond Crown is a crime story where the criminal wins. Or loses. It all turns on which criminal you support. A lady gets a detective to defraud a co-inheritor out of his share in a joint legacy. The detective turns a profit, the others lose. A dark and funny story.

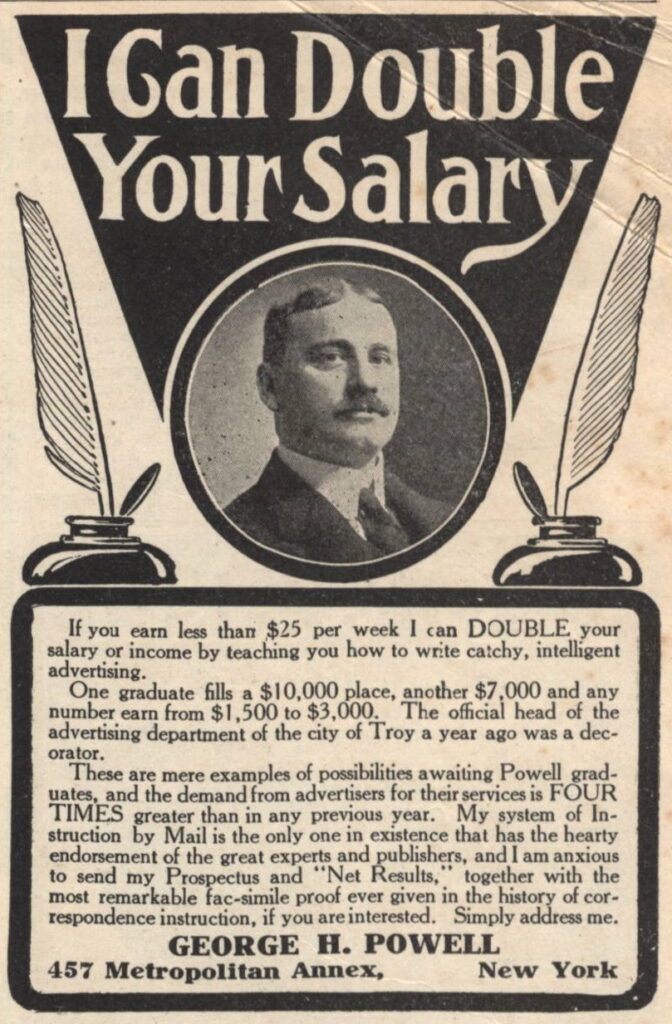

That readership comprised both men and women is also evident from the ads. There are sixteen pages of ads, 40% targeted at men, 30% at women and the remaining targeting both. There are no ads aimed at teenagers or senior citizens. This is clearly a magazine for the middle-aged at home readership. The advertisers are from the same areas as the readers. Apparently, neither readers nor advertisers existed west of the Rockies.

The ads themselves are remarkably modern, not in what they’re offering but in what problems they’re offering to solve – training for new jobs, cosmetics, over the counter medicines and remedies, spring and summer dresses, drug and alcohol de-addiction programs, travel bookings, build your own boat kits.

Two ads stand out for me: one offering to double your salary and the other is something that will probably resonate with the readers of this blog who were used to incandescent bulbs (yellow light) and had to switch to fluoroscent or LED lights (white light). The Angle Mfg. Co of New York pledges to bring yellow light back into the lives of people who had switched from gas or kerosene lamps to newer lighting technologies using mantled gas lamps or acetylene lights. It says white light is the cause of eye strain that can be reversed by going back to yellow lights. Truly there is nothing new under the sun.

To round off the package, there is a section called Stageland at the end of the magazine, a review of new plays on Broadway that would eventually come to the smaller towns with travelling companies if they were successful enough, by theatre critic Charles Darnton. This was complemented by thirty-two pages of photos of actors, actresses and scenes from plays at the beginning of the magazine, printed on slick paper with excellent reproduction quality. This feature continued for the better part of a decade, so it must have been popular with the readers.

What I’m left with is the impression of a magazine in the process of defining a distinct identity for itself. That it lasted for almost fifty years after this issue is proof of its success. A humble beginning for a great magazine.

Sai, it’s a coincidence I know but I’m also reading through my collection of early Blue Books, mainly the 1915 to 1925 issues. I’ve given up on the earlier issues because I think the stories are too dated, uninteresting, or just too bland and naive. Plus I have almost all the issues during 1915-1925 and beyond and as you note, the earlier dates from the 1907 and early teens are very rare and almost impossible to find nowadays.

I just finished the 8 part H. Rider Haggard serial in 1915(The Ivory Child) and was so impressed that I intend to reread King Solomon’s Mines and She. I’m also impressed by the H. Bedford Jones stories during this period. His first tale of 350 for Blue Book(The Wilderness Trail) is quite well done(reprinted by Murania Press) and so are the novelets and short stories that HBJ wrote about the Far East. George Worts wrote an excellent series about a world weary man in the Far East(the Dr Dill series).

I’ll print out this essay on the early Blue Book and put it with my copy of the excellent Mike Ashley history of Blue Book.

Thanks, Walker. I think those earlier issues are better than they look. Not necessarily all the stories match our tastes, but well done all the same.

It’s interesting that you say you like the issues from 1915 on. From 1911-1919, Ray Long (later editor of Cosmopolitan) was the editor and trained Donald Kennicott to handle the buying of manuscripts from authors. The Kennicott touch may be in play and also the trend in general pulps to target them to men.

Re: printing this out, I’m glad to be in such august company. Mike Ashley’s article is a big part of what turned me on to Blue Book. That and a few 1920s and 1930s issues i bought as part of EBay lots.

I own the august 1917 tarzan rescues the moon story issue do you happen to own any of the other new tales of tarzan issues?

Congratulations. Those issues are hard to find and coveted; I don’t have any of them 🙁

I’d go further than Sai regarding the tale with “fantastic elements.” I see it as a still fledging full-out science fiction tale. The elixir of life as a plot device was nothing new, even in 1907, but Coleman, the author, goes to pains to tell us the elixir was made according to a formula, and is thus chemically reproducible. Therefore it ceases to be a “magic potion” (fantasy) and becomes a scientific concoction, thus scientific if not science fiction. And since it is the crux of the story (without it there would BE no story) it cannot be considered a mere “element” — it *IS* the story.

The sardonic downside of the elixir is one that was used more frequently later (to avoid spoilers, I’m not divulging it. Read the story, it’s short). I am almost positive I’ve encountered it in Weird Tales, and in fact seem to remember at least one EC Horror story using the same nasty trick.

The fact is that, taken with all considerations for the market and the time, it’s a darned good little tale, and worthy of exhumation. I bet if Sam Moskowitz had remembered it he’d have included it in one of *HIS* gaslight anthologies.