Who sees your manuscript and how do they decide if its suitable for publication? In 1932, Author and Journalist conducted a survey of editors at Street & Smith, Munsey, Doubleday, Black Mask, Ranch Romances and even the often overlooked Dell and Fawcett groups to find out.

The thing to do, then, was to write to a representative number of editors and get each to answer the questions. We did this. Most of the editors answered and their answers follow. We think they are very illuminating and that they surely tend to give a composite picture of what occurs to that manuscript of yours in the editorial office.

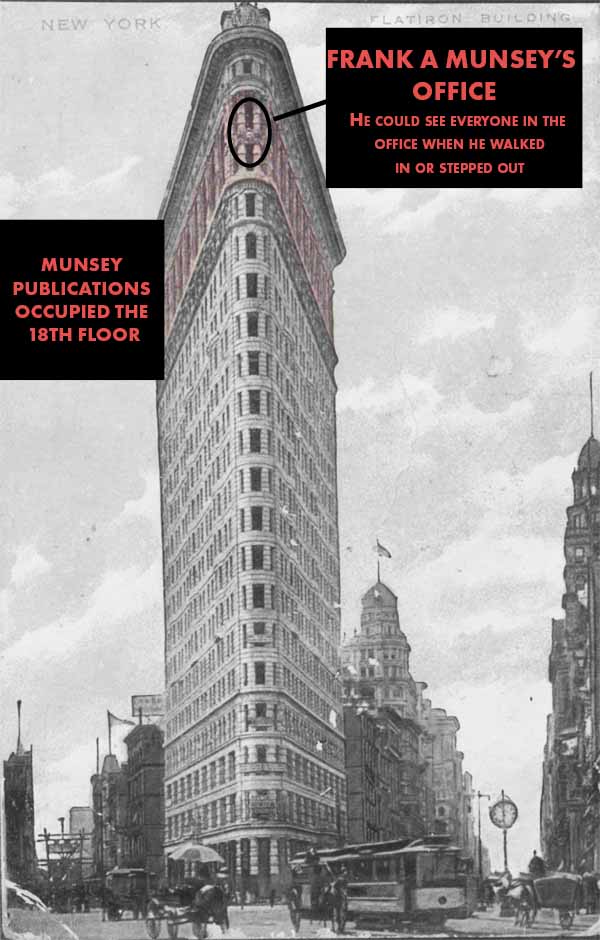

THE FRANK A. MUNSEY COMPANY

(Publishers of Argosy, Detective Fiction, All Story, and Railroad Stories.)

Here is the procedure of handling manuscripts in our office:

Manuscripts are forwarded to a special department where a record is made of title, author and return postage enclosed.

Manuscripts are then sorted and passed on to the associate editors of the magazines to which they are addressed. Each magazine has two associate editors, and in every case both associate editors report on the story.

If a favorable report is given, the manuscript is passed to the editor for his approval or disapproval. Associate editors are always on the lookout for new and promising writers. In cases where both associate editors find a manuscript unacceptable the manuscript is rejected and returned to the author. A record of the rejection and a report on the story is filed with the original wrapper in which the story was received.

Where there is a difference of opinion by associate editors on the acceptability of a manuscript, the manuscript is passed to the editor. If the editor finds the story acceptable it is passed through for payment. Where there is. uncertainty regarding the merits of a manuscript sent by a well-known author, the manuscript is passed to the executive editor for his final decision.

If a new author has a story accepted and has never had anything published previously, he is paid one week after the story appears in the magazine.

Very truly yours,

Betty Flocke,

Sec’y to Mr. Gibney.

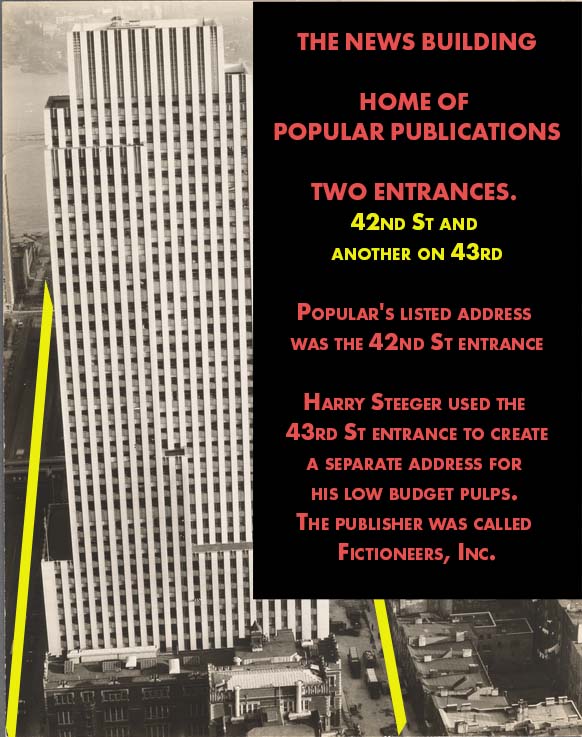

POPULAR PUBLICATIONS

(Publishers of Adventure, Daredevil Aces, Battle Birds, Battle Aces, Horror Stories, Operator No. 5, Rangeland Romances, Star Western, Dime Detective, Dime Mystery, Dime Western, Terror Tales, The Spider, etc.)

I’ll try to answer your letter about the incoming mail bag at our publishing house as briefly as possible.

Manuscripts are first registered and then passed to the assistant and associate editors, who read everything tha`t is sent us. The assistant and associate editors pass on to the editor those stories which they consider suitable for publication, with recommendations as to the value of the story, or suggestions as to changes “that will be necessary before the story is printed. The final decision in each case rests with the editor.

If there is any doubt about a story, it may be read by several assistants, each of whom adds his comments. The inducement to the assistant to discover promising new writers is that in so doing he betters his own position with the company.

Manuscripts are returned by both the assistants and the editors.

Sincerely yours,

Harry Steeger,

President.

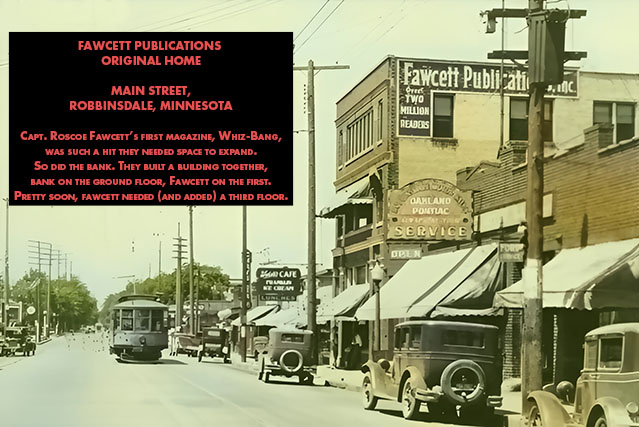

FAWCETT PUBLICATIONS

(Publishers of True Confessions, Romantic Stories, Startling Detective Adventures, Daring Detective, Motion Picture, Movie Classic, Screen Book, Screen Play, Hollywood, Radioland, Romantic Movie Stories, etc.)

Here is the dope on the routine of what happens to a manuscript in this organization.

Mail sacks of incoming manuscripts are delivered directly to a central manuscript bureau where clerks immediately sort the MSS. intended for the various books, give each manuscript a number, and record the title, name and address of the writer, and stamp on the envelope in big figures the date ten days after receipt which is the deadline for action on the part of the editor, thus assuring acceptance or rejection within ten days in nearly every instance.

Manuscripts are then delivered to the individual editors, who generally glance through the pile for specially ordered material.

This organization no longer employs readers as such. All manuscripts are considered first either by the editor or his first assistant, thus assuring all writers that competent persons close to the immediate needs of each magazine see their manuscripts. Unacceptable manuscripts are quickly weeded out. Those considered more seriously are placed in what is called an acceptance envelope on which a brief synopsis of the story or article is written, followed by the comment of the editor or one of his assistants and recommendations for outright acceptance or for further consideration or revision. While this is going on, the rejected manuscripts have been returned to the manuscript bureau, where they are checked out and returned to the author.

Stories that the editor definitely decides he wants to purchase are priced by the editor and sent to the office of Douglas Lurton, supervising editor, who reads the synopsis and editors’ comments on the acceptance envelope and many of the actual manuscripts.

Generally the editor’s OK is approved. Then the editor immediately issues a check memo calling on the business department for payment.

In this organization there is no special reward for the finding of new writers, for that is not necessary. Each editor is always in need of competent new contributors and I believe every editor considers it part of the reward of his work when he can find a beginning writer he considers worth developing. There is probably not an editor in the organization who has not at one time or another turned up a new writer and bragged about it. In addition to this, editors more often than might be supposed drop a writer a line telling him that such-and-such a magazine is apparently in the market for the story he has submitted, even though it is not down the alley for the book that editor is working on.

There are writers who owe their first breaks in the Saturday Evening Post, American Magazine, and several other top-notch publications to tips given them by Fawcett’s organization.

Due to the specific nature of many of the Fawcett publications, many of the articles and stories appearing in them have been outlined to the editor to get his reaction before the manuscripts were ever submitted, and competent queries are always welcomed when a writer has a story or an article very definitely in mind. There are, however, too many beginning writers who will tell an editor that they have written a love story and say, “Are you interested?” That type of query is valueless.

In the New York offices where four of our magazines are being edited, Laurence Reid, managing editor of those books, has the final say on manuscripts, although the individual editor’s judgment is supported in probably ninety-nine cases out of a hundred. The same situation holds true in the Hollywood office, where Jack Smalley is managing editor and, with his staff, acts as a clearing house on articles and stories intended for the movie magazines of the Fawcett string.

Most of the Fawcett magazines are edited in the home office in Minneapolis where Douglas Lurton, supervising editor, gives the final OK on acceptances and exercises general editorial supervision over all Fawcett Publications under direction of Roscoe Fawcett, the editor and general manager, and W. H. Fawcett, publisher.

Sincerely yours,

Douglas Lurton,

Supervising Editor.

COLLIER’S

All manuscripts received at Collier’s are entered in a manuscript file and given numbers.

Manuscripts are divided first into articles and fiction, and tickets, with space for comment by readers, are attached to the articles.

A group of readers takes charge of both categories. One group of readers devote themselves to consideration of articles, and another separate group to fiction. The first readers have authority to reject.

If a manuscript, article or fiction, passes the first reader, it may be given directly to the fiction editor, or the managing editor, or it may be read first by other associate editors. If approved by the fiction editor and the managing editor, the manuscript is read by the editor, whose judgment is final. In the absence of the editor the managing editor exercises final judgment.

Our entire office staff is concerned to discover new talent. The worth of a reader or an editor is governed by the interesting material discovered and not by the number of manuscripts rejected.

Sincerely yours,

William L. Chenery,

Editor.

THE AMERICAN MAGAZINE

Articles submitted to The American Magazine are sent to the article editor, who reads them, discarding those obviously not suited to the magazine. Those which hold some promise of acceptance are passed on to the managing editor, who decides whether or not they should be passed along to the editor-in-chief. When they reach him he makes the final decision concerning their rejection or acceptance. There is no special inducement for an assistant who discovers a new writer except intense personal satisfaction.

Fiction is handled in a slightly different manner. There’s a young man in the mailing department whose job is to wipe out authors’ identities. With black tape and rubber cement he covers the writers’ names on short-story manuscripts that come to The American Magazine. From this point each story must stand or fall on its quality alone—regardless of who wrote it. The sealed manuscripts are then routed through the editorial department as follows:

The First Reader reads all, and eliminates those obviously unsuitable. The stories that pass are taken to the Chief Reader—who selects those he considers good, then sends them to the Fiction Editor. The stories he recommends are passed along to the Managing Editor, following whose okay they reach the Editor—who alone has the power of purchase.

Only after a decision to buy or reject has been reached is the tape removed from the author’s name. Naturally, big writers often come out on top in this acid test of quality. But frequently, through sheer merit, a brilliant new author breaks through.

We hope this outline of our editorial procedure will give you the information you seek.

Sincerely yours,

Mabel Harding.

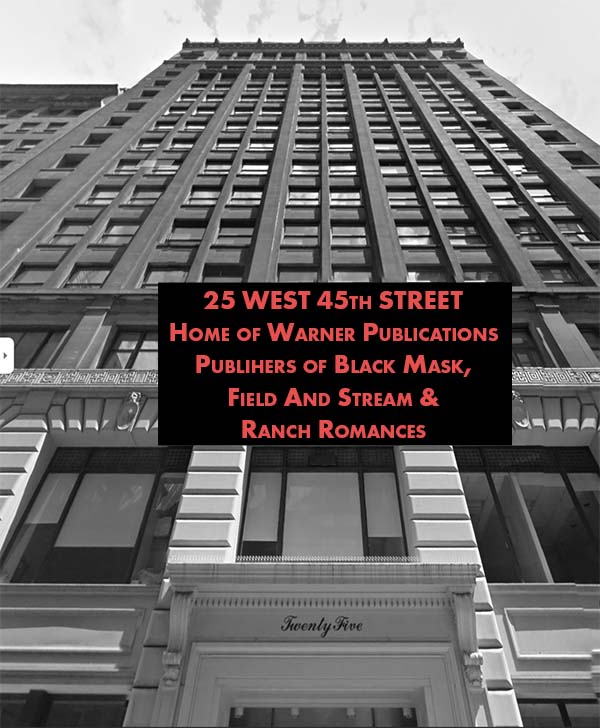

RANCH ROMANCES

I can well understand that writers are interested in knowing how their manuscripts go through the works in an editorial office, and here is the low-down on Ranch Romances.

In the first place, I read all the stories that come in from regular contributors. If I am sure they are good stories for Ranch Romances, I buy them, and if I feel certain that they are not for Ranch Romances,

I reject them. If, however, I am in any doubt—in other words if I get a story that seems to be on the borderline—I get an opinion from one of the girls who work with me on the magazine and we talk the story over.

These girls, of whom there are two, read all the manuscripts from unknown writers and from people who do not regularly contribute to the magazine. When they find a story that seems at all possible for us, they give it to me with a detailed synopsis and an opinion. In that way, new writers who have submitted a story at all promising get two readings. As you probably know, I make the final decision on all stories.

I imagine this is about the same system used by most houses, although a good many of them have all manuscripts read by a first reader before being passed on to the editor. I feel, however, that, since I have to make the final decision, it saves time to have stories from regular contributors come straight to me.

I trust this is about what you want.

Sincerely,

Fanny Ellsworth,

Editor.

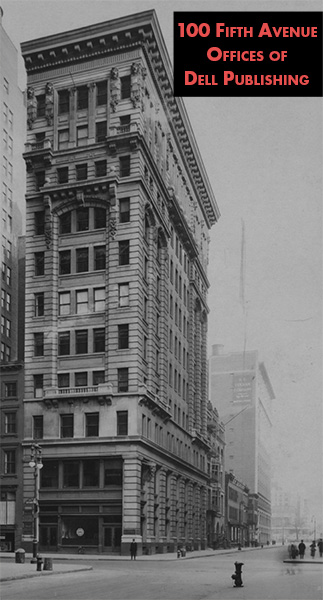

DELL PUBLISHING COMPANY, Inc.

(Publishers of All Western, Five Novels, Modern Romances, Sweetheart Stories, Western Romances, Ballyhoo, Film Fun, etc.)

There isn’t much new we can tell you about the treatment of an author’s brain-child when it enters the publishing house. The procedure is much the same in all of them that I have ever seen. Possibly though. I am a little too callous to the procedure and overlook the interest it carries to the author, even though I was on that side of the fence for a number of years.

When a manuscript arrives, it is placed in a pile in front of the first reader. This gentleman or fem, as the case may be, plays a rather important part, in that his judgment of a story must be such that no good material is rejected.

You may rest assured that every manuscript is read in full or at least to that point which will convince the reader that it is worthless. This reader gives a full synopsis of the story, under which he writes his constructive comment as to the favorability of the story. If it is not sufficiently good but can be revised, it is necessary for him to state just how a revision can he made.

There is always an incentive to readers in finding new authors. The incentive being that when a reader becomes sufficiently valuable to his publisher in story judgment, he usually advances to a much better position than that of reading.

The story is then passed on to another reader or assistant editor who in turn writes his comment on it. By the time at least three readers have read the stories they are passed to the editor, who in many cases reads the synopsis and comments before reading the manuscript itself. If the three readers agree that the story is useless, the editor rarely reads it through. If, however, there is a disagreement among the readers or there is a synopsis that interests the editor, he will read the story before passing on it. Should he like the story, he signs the voucher for the amount to be paid to the author and forwards it to the business office.

This is a rather brief summary of what goes on in our office. But it is rather the same in most other publishing offices.

Sincerely,

Carson W. Mowre,

Editor, All-Western.

THE AMERICAN BOY

When a story or article reaches us, it goes first to a manuscript secretary. The secretary enters it in a manuscript ledger, alphabetically according to the name of the author. In addition to the name of the author and his address she sets down the title, and the number of photos, diagrams or other exhibits that may accompany the manuscript. She notes, too, the date of receipt. Later, when she “checks out” the manuscript, she’ll complete the ledger account by noting the date of return or purchase. In this way, as you will observe, we keep a careful record of each manuscript, and information that will let us make sure that we return all photos or other exhibits.

We aim either to buy or turn down a short manuscript within four days of the time it reaches our office. We adhere to this rule very well, if a manuscript reaches us early in the week. If it comes on Thursday or Friday, however, the week-end is likely to intervene before it gets full attention. Our office closes on Saturdays.

The first reader, who is always our newest editor, returns all stories that are hopelessly written, or that fall outside our field. (I am continually surprised at the large number of stories which, I should think, the authors might know would not be our kind.) He passes along, always with a memorandum, stories he .thinks we might use, stories which have a chance of getting by, stories which though not our sort nevertheless are promising as to style, and stories by writers who have sold us before, or who have a special claim on unusual attention.

The second reader is a long experienced editor. Stories he believes good enough for publication, or good enough with fixing, and stories which seem to indicate author promise, he passes along. The others he returns with a letter.

It then becomes up to me to buy or return. If I return. I almost invariably do so with a letter.

While there is no special inducement for the first reader to discover new writers, I have never known one who wasn’t eager to do so. A first reader’s reason for existence, after all, is to find usable material. He’s known for that, and not for the manuscripts other editors never see. We once had a very enthusiastic first reader who used to follow his manuscripts from desk to desk, pleading their cause. First readers are generally, I think, a new author’s best friend.

As I have often said before, it is my firm belief that an editor is genuinely proud of not more than 15% of his book. The rest he prints because he can’t get anything better. In that ”passable” 85%, therefore, lies the new writer’s opportunity.

The American Boy is unusually friendly to new writers.

Sincerely,

George F. Pierrot,

Managing Editor.

THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY

Every manuscript which reaches the Atlantic is read by a first reader, and all those which seem worthy are read further by two others. The final decision is made by the editor in the light of the various comments. Great care is taken, so that no interesting manuscript escapes us. We cannot recall an instance when an unusual paper was lost to the Atlantic through inadvertence.

Yours faithfully,

The Editor.

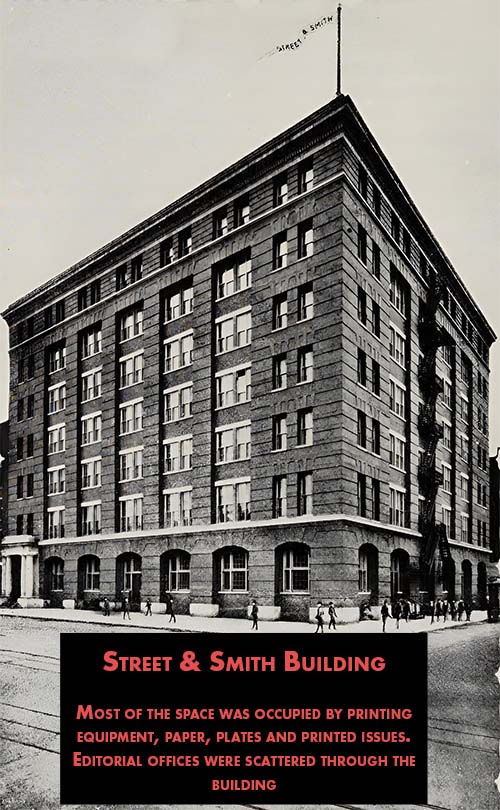

STREET & SMITH PUBLICATIONS

(Publishers of Ainslee’s, Love Story, Western Story, Detective Story, Wild West, Top-Notch, Street & Smith’s Complete Magazine, Sport Story, Best Detective, The Shadow, Picture Play, Nick Carter, Doc Savage, Clues-Detective Stories, Astounding Stories, Cowboy Stories, Pete Rice, Bill Barnes Air Trails, Western Winners, Romance Range, Dynamic Adventures.)

The question you raise could be answered and dissertated upon at great length by the humble subscriber of this letter. The routine as to what happens to a manuscript from the time it is received by Street & Smith Publications until it is returned or purchased is, of course, very simple. My knowledge of the Street & Smith method of considering manuscripts extends over twenty-five years. It has remained the same during that period. (The reader may find it interesting to compare this statement with this article I previously published on S&S handling manuscripts in the 1920s.)

There are three large boxes in the editorial office of each magazine. These boxes are marked in order, “To Be Entered,” “To Be Considered.” “To Be Returned.” When the mail is sorted, all manuscripts directed to a magazine are put in the box of that magazine which is labeled To Be Entered. A clerk from the department which handles all manuscripts in a clerical manner removes these manuscripts and enters them in a book. This entry consists of noting the author’s name and address, the title, when the manuscript was received, and the amount of return postage enclosed. Having done this, the clerk places the entered manuscripts in the To Be Considered box.

It depends on the number of assistants an editor has as to how many readings a manuscript receives. “The final power of veto and acceptance” rests with the editor of each particular magazine. There is no “special inducement for readers to discover new writers,” but as the sustenance, growth, life of a magazine depends on getting new writers, a reader or assistant who discovers new writers, good stories, grows in the esteem of his editor and in the esteem of Street & Smith.

The article, “Getting Through the Story Filter,” by Arthur Hawthorne Carhart in The Author & Journalist for September describes as well, it seems to me, as anyone could describe, the editor’s big problem. Mr. Jack Byrne stated this problem to Mr. Carhart in a most elucidating manner. It is the contention of that great editor, Mr. S. S. McClure, who has always been a good friend of mine, that the editor of a magazine should be the person to read all stories from the To Be Considered box. But, as Mr. Byrne says, “it can’t be done.” However, if an editor is very close to the person who reads the stories in the To Be Considered box, it is not likely that anything really good will get by. Like Mr. Byrne, I have had many readers who “read the box” without the courage of their own convictions as to what the editor should have, but rather with the idea of reflecting the editor’s judgment as to stories. A good reader should have the courage of his own convictions, and I plead daily with readers to tell me how they feel about a story, and not to tell me how they think I would feel. I also plead with them to go through the To Be Considered box with the burning hope of a prospector. I also like readers to pick up a manuscript with the feeling that the story is going to be a good one, and that it is up to the author to prove to me that it is not a good one. Beginning readers are almost invariably inclined to put themselves in the position of critics, and they start reading a story with a tight-lipped attitude and a determination to find out what is wrong with it, as a schoolmaster would correct a pupil’s exercise. This, of course, is all wrong. It is the .author who must prove to the reader that his story is a poor or a good one, not the editor who must prove to the author that his story doesn’t pass.

Of course, the experienced reader does not have to go far in the bulk of stories he receives to discover that they are unavailable, that the writers just aren’t craftsmen enough to tell any story well. Many years ago in my early days here I was painstakingly going through the To Be Considered box, reading well into, if not finishing, all manuscripts. One of our best editors at that time came into my office and said, as he found me pulling a manuscript from its container, “Why, you look inside the envelopes, don’t you? That’s a great waste of time.” Now, of course, he didn’t literally mean that, but he was a man of vast experience in what is known here as “cleaning out the box.” He had found that a glance, a peek inside the envelope which contained some manuscripts, was actually enough to show it was unavailable.

In closing this long dissertation, I can assure writers, beginning and trained, that all the editors working for Street & Smith find that their hardest problem, their biggest worry, is to find good stories by new writers. Also, that this is the biggest part of their job and that they realize it. It follows, then, that the new writer may feel sure that the editors and readers of Street & Smith will give any manuscripts sent here all the consideration they deserve. It would be too much to say that nothing good ever slips through our fingers. That would be absurd. But I really don’t think that anything, certainly that which is above the average, very often gets missed in an editorial lifetime.

Yours very truly,

F. E. Blackwell,

Editor-in-Chief.

A further note from Ronald Oliphant, editor of Sport Story and other Street & Smith magazines, comments :

With regard to Arthur H. Carhart’s article, I think that writing a story according to a fixed formula is taking the line of least resistance. Naturally, there are certain rules and tricks which help to put a story across, and it is only natural that authors should use these devices. We are always glad to see a story that has not the same cut-and-dried plan of development, but such stories are harder to write and harder to put over to a reader.

1 do not believe the general run of editorial readers are blind to the merits of a story that is not constructed according to a set’ pattern or formula. In fact, I often say to my readers that we make a great many mistakes in buying stories, but we never make the mistake of turning down a really good story. Yours very truly,

Ronald Oliphant.

THE DAVID C. COOK PUBLISHING COMPANY

(Publishers of Sunday School literature and story papers, including Boys’ World, Dew Drops, Girls’ Companion, What to Do, and Young People’s Weekly.)

We should like to make a helpful contribution toward your plan, but fear that our system is not sufficiently elaborate or intricate to attract any special attention.

When a manuscript is received it is entered on records by an office stenographer and filed for reading at the proper time. All manuscript which reaches us by the 25th of the month is read and reported upon by the 10th of the month following. That which arrives after the 25th of the month is held until the second month following.

Manuscript is first read by an assistant editor who makes several classifications as to type and merit, or marks for rejection because material does not conform to editorial policy, or for some reason is definitely unavailable.

Later, the managing editor of the publication reads the manuscript, and in most cases, makes final decision as to whether or not it is acceptable. The return of a manuscript does not necessarily imply that it is not meritorious or that it would not be accepted by publications of a different nature. Many times we are overstocked with certain types of material, and for this reason cannot purchase manuscript even though it conforms to our policies and is of a high order of merit. If, at any time, the managing editor is in doubt as to advisability of acceptance or rejection of manuscript. he advises with the editor-in-chief before making a decision.

For the information of your readers, we might add that all manuscript submitted to us should be prepared with the needs of the publication for which intended definitely in mind and should be addressed direct to the editor of the publication for which intended. Manuscript should be typewritten on one side of the sheet only, and stamps enclosed for its return if not available.

All manuscript purchased by us is paid for upon acceptance. Rejected manuscript is returned to the writer following regular monthly reading, as per schedule mentioned above.

Trusting that these brief statements will be of some interest to your readers. I am.

Very truly yours,

David C. Cook III,

President.

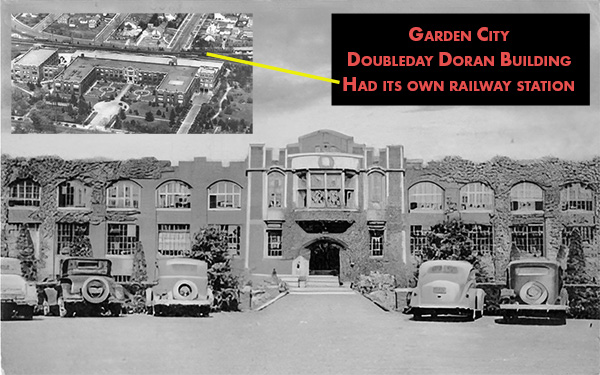

SHORT STORIES

Published by Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc.

We like to think that both our old friends and new writers get the best possible consideration from Short Stories, and our routine is all keyed to this purpose. All the manuscripts are opened, recorded, and placed in piles—serials, stories from old contributors and stories from new ones, articles, etc. The managing editor sorts them to assign for reading by the assistants in the editorial department. Every item is carefully read by at least one competent editor. The obviously impossible ones are returned on one reading. The more promising ones are reassigned for further reading, each reader making a written report which contains an outline of the story and comments upon its availability, its strong points and its weaknesses. If revision is indicated, that too appears in the reports. These stories with the reports come back to the desk of the managing editor and frequently call for a conference of the editorial staff to decide differences of opinion, questions of policy, etc. All the accepted ones are finally passed on by the editor, whose O. K. must be on every voucher before a check can go out.

It is a red-letter day with all of us when a good story comes to light by a new author. Short Stories in its long history has printed “firsts” by many popular nationally known writers—and new angles, new slants and new settings are eagerly sought for—within our accepted field of action fiction, of course. Our rule is for payment two months before publication, but in special cases we have been known to get a check through in two hours after accepance—no mean accomplishment when one considers the elaborate accounting system of the huge organization of which we are a part.

If I might offer a comment on Mr. Carhart’s article in the September Author & Journalist, it would be that undue emphasis seems to be placed on editorial likes and dislikes. What his readers want is what every editor wants and that is what—both from old and new authors—we are striving to find here on Short Stories.

Yours sincerely,

Harry E. Maule,

Editor.

BLACK MASK

Briefly: All manuscripts received by this office are recorded as received, and examined in chronological order. The acceptable ones are paid for promptly. Those of which we cannot avail ourselves are again checked and returned as speedily as we can determine their unsuitability.

With every manuscript returned, we endeavor to send some word, however slight, with regard to its unacceptability by us. In the same way, we try to clear decks within three or four days of receipt. I say try, because with every manuscript brought to my personal attention and with approximately two million words to pass on monthly, it is often impossible to keep strictly up to date. And often an unacceptable MS. contains enough of promise of later capability to invite a closer study and, with other work intervening, such opportunity may well be delayed, although it is not purposefully to the disadvantage of the author.

I trust that this necessarily brief resume will give you what you wished.

Joseph T. Shaw,

Editor.