A recent rummage through some boxes turned up two copies of Black Mask, and I started reading them. One was from the thirties, another from the forties. I thought it might be interesting to review a few issues to see the difference in editors as the magazine changed.

As I did that, I found some fascinating information. Armed with information, some of which I don’t recall having read earlier, I decided to do a series of posts on the history of Black Mask. The reviews of selected issues would provide examples of my points.

When you read this, keep in mind that I had very limited access to early issues, which are scarcer than those of any other major pulp. My main source for those issues was the Pulp Magazines Project, where a bunch of early issues are scanned and the FictionMags Index, which gives a list of the contents of every issue and a picture of each cover. My coverage of those years, then, is based on only a few issues. If you have read early issues and think I’m wrong (or right), leave comments.

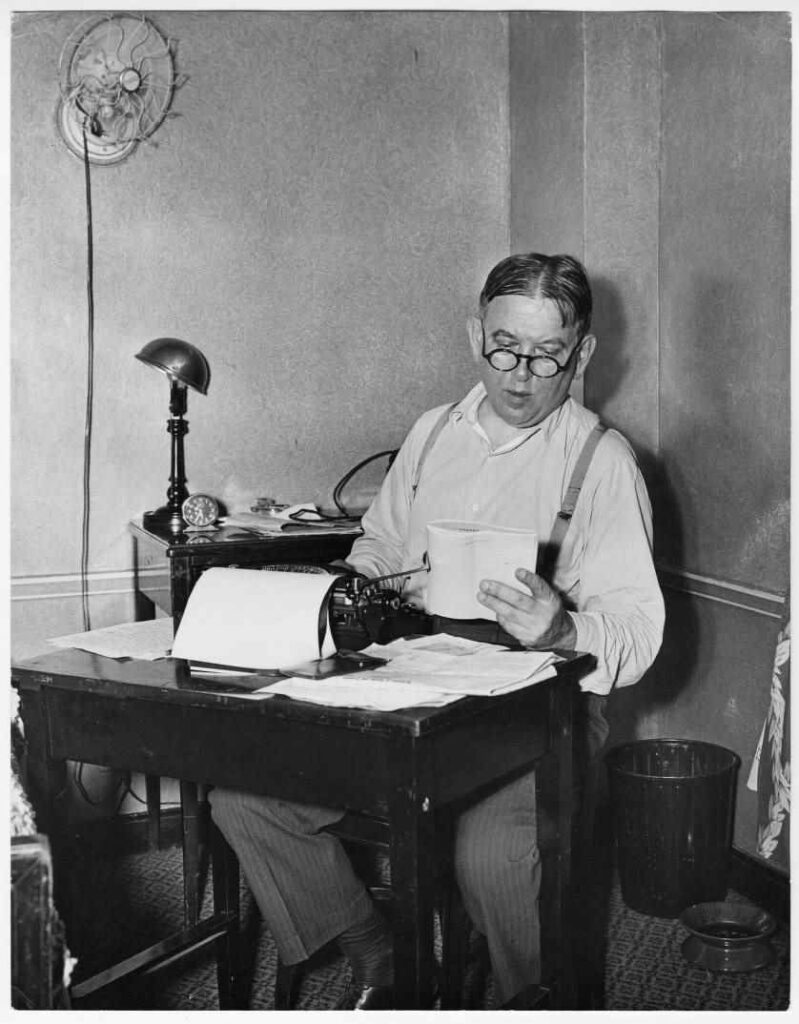

Black Mask was the brainchild of H. L. Mencken (a journalist) and George Jean Nathan (who was working as a theatre critic), backed on the business side by Eltinge F. Warner, the publisher of Field and Stream. Warner was the publisher of Smart Set; which had come to him when the previous publisher was forced to give up Smart Set to his chief creditor, Eugene B. Crowe. Crowe, having no desire to run it, appointed Warner as publisher. Warner, looking around for editors to run the magazine, managed to get Mencken and Nathan to sign up for the job.

(Photo from the University of Baltimore)

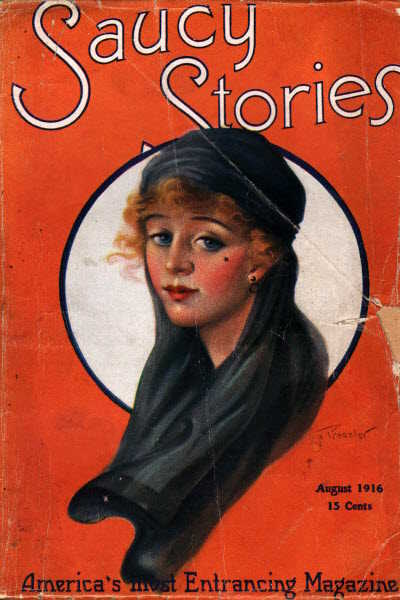

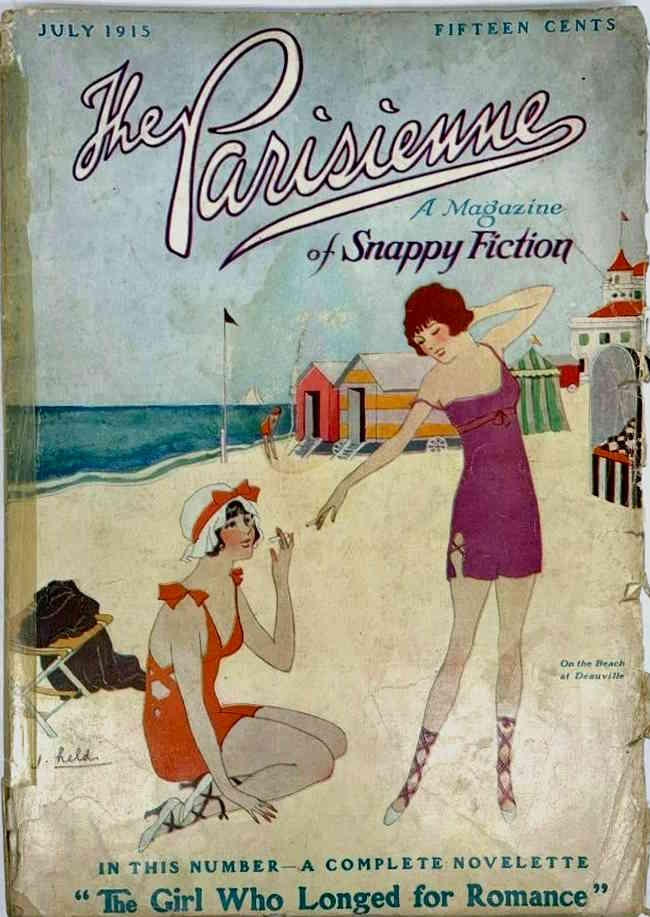

(From Cornell University)

Why did this unlikely trio start a pulp magazine? Warner, who was initially losing money on Field and Stream, needed cash to support it. Mencken and Nathan wanted to keep running The Smart Set, a steadily loss-making enterprise that they considered to be their best work. Mencken and Nathan had previously tested the demand for pulps with two slightly risqué titles – The Parisienne and Saucy Stories – and then, once they were selling well, sold them to Warner for cash.

Now very few remember The Smart Set and Black Mask has legendary status as one of the best pulp titles. Goes to show that you can’t trust Mencken’s critical judgement all the time.

Warner, Mencken and Nathan worked behind the scenes. Listed on the table of contents are A. W. Sutton (President), F. M. Osborne (Editor) and J. W. Glenister (Circulation Manager). Sutton, the third son of a rich businessman, worked as a stockbroker and treasurer of Warner’s Field and Stream.

John William Glenister, who had been working with Warner since 1916, had a colorful past. He had worked as a newsboy, been a champion swimmer who did vaudeville exhibitions and promoted health tonics before turning to newspaper work as journalist and then sales manager. In February 1919, Warner sent him to England to negotiate with British publishers for publishing a UK edition of Saucy Stories and The Parisienne.

Since Mencken and Nathan were busy with The Smart Set, they needed someone to edit their pulps. Listed on the contents page as F. M. Osborne is Florence May Osborne (1880-1961), Wellesley graduate (class of 1902), who started her career as a librarian. She became an editor for a time in the 1920s, editing Mencken and Nathan’s string of pulps.

Mencken in his autobiography, My life as an author and editor, says: “A woman named F. M. Osborne was put in as editor toward the end of 1920, and Nathan and I began to collect $50 a week for supervising her. Unhappily, she was incompetent, so the job failed as a means of collecting unearned increment, and involved us in a lot of hard work”. Was he correct?

It’s hard to say unless you compare it to the competition. Street and Smith’s Detective Story Magazine was Black Mask’s only competitor (Flynn’s was launched in 1924); it had been on the market for seven years. DSM had struggled through a couple of years of dime-novel fiction before establishing itself with a set of regular authors and series characters, the one thing missing from Black Mask. The other stories were similar to the ones in Black Mask.

Was the ratio of good to bad fiction in Detective Story in those early years higher than in Black Mask? Read my review next week of the August 1922 issue, the next to last issue published under her editorship to find out.

Osborne tried to make a magazine that offered quality fiction for both men and women. Many covers had women as subjects. Crime was subdued, physical violence was rare if not absent, and women authors contributed fiction with romantic elements.

Osborne’s editorial presence is invisible – there are no regular letter columns or chatty editorials. Illustrations for each story were missing at the beginning but added later. William Grotz, the cover artist, also did the interiors. Well done, but, like the magazine’s fiction, these illustrations had no identity of their own and could have equally well been from any general fiction pulp of the time.

Glenister left Warner in 1920 or 1921. Mencken says Glenister had made himself a middleman between Warner and his British publishers, earning money for every copy sold in the UK. Warner found out and sacked Glenister.

What I know for sure is this. Glenister, on leaving, formed a publishing partnership with Jack B. Kelly; their first title was Action Stories and its success led to the establishment of Fiction House as a major pulp publisher. I saw an advertisement in Black Mask for Action Stories, and presumably vice versa. Rival publishing houses didn’t promote each others titles. Does that mean that Glenister and Warner didn’t part on bad terms?

P. C. Cody was hired as Glenister’s replacement. He would play an important role later.

While the circulation of individual magazines wasn’t reported, the Parisienne group under which Warner reported the circulation of The Parisienne, Saucy Stories and Black Mask didn’t show any major changes from 1920-1922. Which would probably mean that Black Mask’s circulation was not growing. Or falling, if the other two were growing.

It was time for a change in the formula. Osborne left Black Mask in 1922 and edited Movieland and Shadowland magazines before returning to library work, which she did for the rest of her life.

Next week: Secrets of the Mask, part 2: Inside the September 1922 issue

Back in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s I managed to put together a set of Black Mask. Back then it was possible and quite inexpensive because just about no one collected the magazine. Most collectors concentrated on SF and hero pulps. Also Max Brand issues were sought after by many. UCLA was trying to put together a complete set and I knew a collector named E.H. Mundell who had a couple hundred issues. I sort of created my own competition by talking about the magazine so much, so Jack Irwin, another collector in the Trenton, NJ area, also started to collect it. That was just about it back then for interest in Black Mask(Ron Goulart also had a big interest but I bought all his Black Mask issues).

I did a lot of reading in the 1920’s and one thing I found out right away, was that the early issues were not of high quality. Before Joe Shaw took over in 1926 there was very little of interest except for Hammett and Daly. I would have to say the issues in 1920 through 1922 were very close to being unreadable by today’s standards. Very dated stories, poor characterization, and bland, uninteresting plots.

Then Hammett and Daly started publishing and things improved. One special issue of note was the KKK issue which published stories pro and con. When Shaw took over in 1926 he encouraged more writers to writers to study and write like Hammett.

So I would have to say the really interesting period started in Black Mask with the Joe Shaw issues and even then it took a couple years for Shaw to get together a stable of hard boiled writers. The peak Shaw years were 1929-1936.

Then I see the next quality period to be the Ken White years under Popular Publications during 1940 to 1948. By the way, Sai, you have started off on an excellent project studying an important detective fiction magazine. I look forward to your future essays.

Hi Walker, Great to hear from you. I can’t really disagree with you about Cody and Sutton’s reign, given I haven’t read any issues from their time. But I’d like to see you dig out some of the notes you made on the first two years, if you still have them.

It seems to me that Osborne’s Black Mask was different from Detective Story Magazine, which was still catering to a dime novel audience looking for masked avengers. Osborne’s Mask may not have been as uniformly good as a 1930s issue, but then how many other pulps hold up to that standard? Very few, I’d say. Given time, she might have taken it in a different direction.

Let’s see if you agree with my opinion next week.

Thanks for posting this story. Very readable and certainly fits the timeline in which it was published. Being a BM collector, I only have two or three issues from 1920-1922, so I can’t really recommend any other stories from that time frame which might be worth reprinting. That said, I agree with Walker on BM’s best periods, from 1929-36 (Shaw’s reign), and then the Popular Pub. years. It would be interesting to have that short story collection by Winslow and see if the other stories are any good.

Nice work, Sai. Good detective work in finding pics of all those important execs… I don’t think I’ve seen any of them before.

Thanks, Matt. Toughest was Florence Osborne’s picture.

Really like this material, Sai, thank you. I’ve been curious about earliest Black Mask issues as well.

I’ve never quite gotten Mencken’s attitude towards the pulps. I guess mercenary is the term I’d use (plenty of pulp publishing mercenaries out there through the years and dare I say right up to the present.) I’ve got a ton of respect for him both as author and critic in almost all areas, but he seems to have zero respect for the pulps. I daresay that this is why he’d stoop to hire a woman editor in Florence Osborne (besides you didn’t have to pay a woman editor as much – there were other women editors in the pulps and mags of the 20s, too). I’ve seen various places where Mencken displays open contempt for pulp readers (The Parisienne is the one I’m thinking about but don’t doubt he felt the same way about Black Mask). The weird thing is he has this sort of democratic aesthetic but also a literary snobbery that shouldn’t go hand in hand – but, you know, containing multitudes and whatnot.

Also of interest to me is the idea of the UK agent. The way that foreign editions worked in the pulps is a pretty murky area for me, so I’m happy to learn a little more (and the particular story of Glenister getting canned for skimming is pretty fun).

I’d note Shadowland is pretty much a classic American magazine (I haven’t really studied it outside of reading a number of the issues at the Internet Archive), so I’m interested to take a look for myself at these early issues I havent read over at the PMP and seeing what Osborne was up to and also exactly what hand she had in Shadowland.

I try not to make too many presumptions about what may or might not be good pulp because, frankly, there’s a whole lot of assumptions at work in the old fan culture that I’ve found to be totally untrue (not to discount Walker’s opinion in any way – from what I’ve seen he knows his pulp). You just have to read em yourself, eh? Ofc Hammett, Cain, Daly,etc. are the big names later on, but mebbe there’s some good writers in these earliest issues, too. I’ll check em out and follow along with you in your series

-Beau

Beau, what a great comment. This is the kind of stuff that makes me want to write more, so that we can actually discuss the contents and not just the covers.

> Mencken…seems to have zero respect for the pulps.

> Which might be why he’d stoop to hire a woman editor in Florence Osborne

> (besides you didn’t have to pay a woman editor as much…

You hit the nail on the head I think. Unlike the sex story market, the detective fiction market had competition and needed a full-time editor to make a difference. I think Osborne did a competent if not outstanding job. Given time and the right support, she might have made the magazine successful.

> I try not to make too many presumptions about what may or might

> not be good pulp because, frankly, there’s a whole lot of assumptions

> at work in the old fan culture that I’ve found to be totally untrue

Yeah, I think approaching the pulps with an open mind and gloved fingers is a good idea. Too many people go by other’s opinions and just looking at the covers as if that were representative of the entire magazine.

Next week we’ll take a look at the last but one issue edited by Osborne and see what we can find out.

Best

Sai

This is a great article and a great piece of research – I was pointed to it by”Darwination” over at the CGC forum.

I’m currently researching the history of UK publisher Atlas Publishing & Distribution Co Ltd, and your mention that J.W. Glenister was dispatched to the UK in 1919 to negotiate UK editions of Saucy Stories filled in a gap in my knowledge. Atlas Publishing & Distribution Co Ltd was set up by William Stephen Dexter and J.J. Young in 1914 to provide content for Dexter’s wholesale newsagent business and his growing chain on bookshops in London. As far as I know Saucy Stories was the first US pulp that Atlas published in the UK, followed by Black Mask in mid 1923. I understand that both UK editions of Saucy Stories and Black Mask were initially printed in the US for distribution in the UK. Do you happen to know the date of the first Saucy Stories UK edition?

Re your mention of the Inter-Continental team of Sutton, Glenister, etc I would also add the name of later pulp-writer Wyndham Martin (AKA Wyndham Martyn, William Grenvil, William Hosken, etc) who is listed in the US May 1919 issue Vol VI #4 of Saucy Stories as “Editor and Vice-President”, alongside Sutton, et al. I wondered that as Wyndham Martin was a British ex-pat, whether he played any role in identifying Atlas as a potential candidate publisher for UK editions?

> Do you happen to know the date of the first Saucy Stories UK edition?

No, unfortunately not. However I can make a guess based on searching the FictionMags Index that it was in 1922 .

The first issue of Saucy Stories (UK) in the FictionMags Index is dated July 1 1922, and the volume numbering says vol 3 #1. The contents are identical to the July 1 1922 US edition, which is numbered vol. 12 #6. At the time, Saucy Stories was published twice a month, and had 6 issues in a volume.

Given the volume numbers are non-identical, I’d guess that there were two volumes before the July 1 1922 UK issue and that means 12 issues, or 6 months. So Saucy UK publication would started with the Jan 1 1922 issue if we rely on volume numbering and regular publication.

Don’t know enough about Wyndham Martin to hazard a guess on his relationship with UK publishers.

PS. Please update when you have a better picture of what was going on. Maybe a link to articles on your blog.

Sai – Thanks for the replies and educated guess on the start of Saucy Stories (UK) publication.Very much appreciated. I’ve set up a new blog focusing specifically on Atlas Publishing and Distributing, which I will use to hold all the Atlas information I gather. I’d welcome any comments you may have on the first installment, where I document what I know so far about the creation of the company.

I’m particularly interested in uncovering the business relationship between the Waste Trade Publishing Company and Atlas. Waste Trade Publishing renamed itself as the Atlas Publishing Company (Incorporated in NY) on 15th June 1915, and Atlas owner Walter Dexter set up their offices alongside the UK business offices in London.

Take a look at https://atlaspublishinganddistributing.blogspot.com

Nice work. Nothing to add from my side, it’s all new information to me. Keep posting 🙂

I’ve added a few more posts to the Atlas Publishing & Distributing blog, plus updated the previous post. I have expanded on who Glenister met with on his trip to the UK and his initial contract with Dorling Advertising Agency before Warner subsequently made a new deal with Atlas that resulted in the printing of a UK edition of Saucy Stories. All comments and observations gratefully received.

https://atlaspublishinganddistributing.blogspot.com/2024/08/history-of-atlas-publishing-and_12.html

PPS:

The editor of Saucy Stories from 1921 Aug to 1922 Apr (and perhaps longer) was F. M. Osborne, who was also editing Black Mask and The Parisienne. Wyndham Martin wasn’t the editor.

Sources:

https://archive.org/details/sim_writers-digest_1921-08_1/page/14/mode/2up?q=%22saucy+stories%22

https://archive.org/details/sim_author-journalist_the-student-writer_1922-04_7_4/page/3/mode/1up?q=%22saucy+stories%22