The seeds of greatness were there in last week’s review of an early Shaw edited issue, this week we’ll see them blossoming to their full glory in the November 1933 issue and possibly understand why hard times were happening despite that.

The package

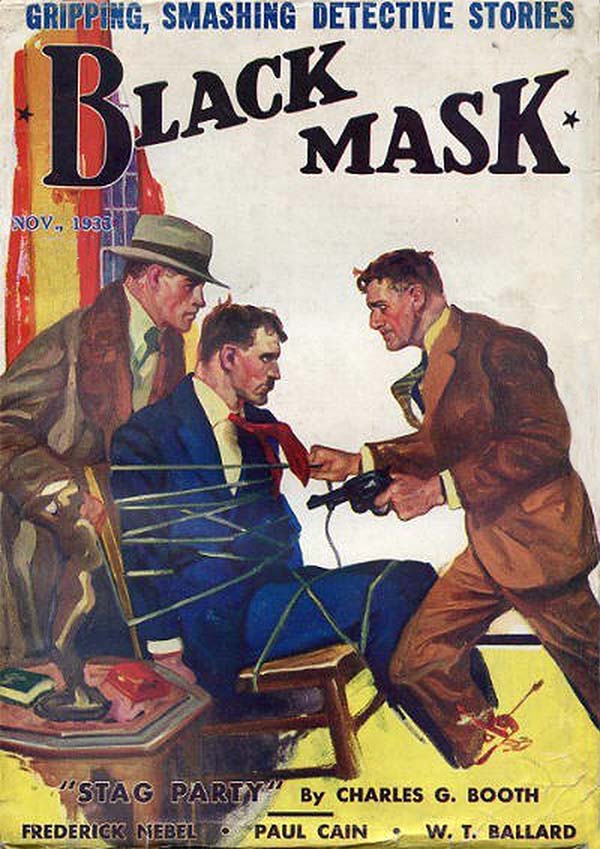

The cover is by J. W. Schlaikjer, whose run of about fifty definitive covers is coming to an end. The scene on the cover is from Stag Party by Charles G. Booth. Earlier covers depicted general scenes, setting a mood; I found this change a bit surprising. Nebel, Cain and Ballard are given cover mentions. The last time we saw the subhead, it was “Western, Detective and Adventure Stories”. Now it’s “Gripping, Smashing Detective Stories.”. The interior art is by Arthur Rodman Bowker, and it’s up to the mark set by previous issues.

The overall page count has decreased. The February 1927 issue had 32 pages of ads, this issue has 8. There are still 128 pages of content with some padding. 2 pages of puzzles, 3 pages of a real life experience. That’s one story less than you could expect. The price is still 20 cents.

Hard Times

On a bad note, circulation which had reached nearly 125,000 copies in December 1929, had been steadily declining. This issue would sell about 60,000 copies, about half of the peak.

Why? One obvious reason was the Great Depression. Starting with the Wall Street crash in October 1929, pulp magazines were dying as people cut back on discretionary spending. The Clayton chain had gone bankrupt in 1930 and had its assets sold off to rivals. The number of pulp titles on the newsstands had dropped from 85 in 1929 to nearly 60 in 1930.

Other possibilities: Hammett was missing. He had written his last story for Black Mask in 1930 and had moved on to the slicks, writing for Liberty, Esquire, Red Book, Cosmopolitan and the American Magazine. Or were the contents putting off readers? We’ll see.

The Fiction

This issue has a bunch of regulars. W. T. Ballard with nearly thirty stories in the Bill Lennox series; Fred Nebel with thirty-six stories in the McBride/Kennedy series and Raoul Whitfield who had over ninety appearances under his own name and the Ramon Decolta pseudonym. Charles G. Booth and Thomas Walsh each had just less than ten stories in the magazine. And then there’s Paul Cain (real name George Sims), whose twenty-four stories in the magazine were the hardest-boiled you could find.

First up is Stag Party by Charles G. Booth. An ambitious “Mr. Clean” district attorney is shot dead in a closed theater. The evidence file that would have clinched his case against “The Boss” of the city is missing. Was it stolen or sold? It turns out Mr. Clean was dating a burlesque performer while engaged to a rich woman. Was she the killer? Our hero, the detective on the spot, gets beaten by The Boss and his goons who want the file. He manages to create a good resolution for nearly everybody. That’s as far as I can go without spoilers. Mid-grade hard-boiled, with a gut-punch ending that doesn’t fully make up for the prose, which is overly lush and verbose in parts. I’m surprised it got the cover mention and the first position in the magazine.

There’s a proverb that God helps fools, children, and drunks. That last part’s definitely true in Lay Down the Law by Fred Nebel. Nebel created multiple series for the detective pulps, the combination of Captain MacBride and reporter Kennedy was the most popular.

Kennedy is an alcoholic, and on this snowy winter night he runs into a drunk woman outside a bar. They end up sharing a cab; he takes her home where she collapses on the floor. Kennedy walks out after fifteen minutes in the flat and mutters something about a big story to two men as he comes out. The two men are thugs being blackmailed by the woman; they start gunning for Kennedy, who disappears. MacBride, triggered into action by a murder, crosses paths with Kennedy and the thugs hunting for him. Nebel’s writing is smooth and suspenseful; the reader’s never really sure if Kennedy is alive and going to stay that way. Recommended. You can find this story reprinted in volume three of the Complete MacBride and Kennedy series from Steeger Books.

THE emergency ambulance had red-tinted headlights and these sprayed a roseate glow on the snow. Its spotlight, not tinted, was flung across the curbing, and men moved within its radiance. A motorcycle with the police insignia stood jacked up on its standard, its putteed officer standing spread-legged before it. The cop on the beat was writing in his book, bending downward and side-wise to take advantage of the motorcycle’s headlight. The snow continued to fall, softly, unobtrusively, and men’s boots crunched in it; voices, even the low ones, were sharp and clear in the cold, and breath spumed.

F Scott Fitzgerald thought highly of Raoul Whitfield: “who I think is as good as Hammett—in fact I once suspected he was Hammett under another name.” I wouldn’t go so far. Whitfield didn’t reveal character through action the way Hammett did; his strengths were terse prose, continuous excitement and near-nonstop action.

All those strengths are on display in Not Tomorrow, which takes place in a single day and night. O’Rory, the Irish detective who’s our hero in this story, is a stereotype: strong, smart, a sucker for women in distress and always looking for trouble and action. He’s hired to retrieve an IOU for a rich married woman with a gambling problem. He retrieves it but the gambler, who wants the IOU to hold over her head for blackmail, won’t go down without a fight. A game of deadly cat and mouse plays out between O’Rory and the gambler as the advantage shifts from one to the other throughout the night. Also recommended.

Paul Cain wastes no words, straight to the action. Like he’s dragging a camera around.

THE woman was bent far forward over the steering-wheel of the open roadster. Her eyes, narrowed to long black-fringed slits, moved regularly down and up, from the glistening road ahead, to the small rear-view mirror above the windshield. The two circles of white light in the mirror grew steadily larger. She pressed the throttle slowly, steadily downward; there was no sound but the roar of the wind and the deep purr of the powerful engine.

There was a sudden sharp crack; a little frosted circle appeared on the windshield. The woman pressed the throttle to the floor. She was very pale; her eyes were suddenly very large and dark and afraid, her lips were pressed tightly together. The tires screeched on the wet pavement as the car roared around a long, shallow curve. The headlights of the pursuing car grew larger.

The second and third shots were wild, or buried themselves harmlessly in the body of the car; the fourth struck the left rear tire and the car swerved crazily, skidded halfway across the road.

Pigeon Blood is collected in The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps. Both the story and the collection get my warmest recommendations.

Positively the best liar offers a little ironic relief from the hardboiled stories that precede it. W. T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox is a troubleshooter for a Hollywood studio, a man who makes sure the studio’s stars shine bright with no hints of darkness in their public image. This time he’s called out to help the studio head set his daughter’s head straight. She’s seeing a French count, an unpleasant character who sashays into women’s hearts and exits with their money. But she’s blinded by her infatuation and can’t see through him. Lennox helps. Ballard’s plotting is good, the twists in the story intriguing and the climax where Lennox wins the title sobriquet (Positively the best liar) turns the situation around convincingly.

Tip on the Gallant by Thomas Walsh is a letdown. It suffers from a complicated plot and too many characters involved in a murder on a train. It’s his second published story. He must have gotten better over time; enough to win the Edgar Award for his first novel, Nightmare in Manhattan (1949). Skip this one, though.

The contents are above average, so that shouldn’t be the reason for the circulation decline. The answer must lie somewhere else.

Brother, can you spare a dime?

Take a look around a newsstand that month. On one side are the gangster pulps, featuring rat-a-tat machine gun action so hot the issue smokes when you open the cover, with stories by Anatole Feldman and Margie Harris. Priced from 15 cents to a quarter an issue. They’re comparable in price, if not in quality.

Near them are the detective pulps. The top shelf ones are Munsey’s Detective Fiction Weekly(DFW), Popular’s Dime Detective(DD) and Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine(DSM). DFW, published weekly with 144 pages an issue, offers a wide variety of stories from recognizable pulpsters like Judson Philips, H. Bedford-Jones, Frederick C. Davis, Fred MacIsaac, T. T. Flynn, George Harmon Coxe and last but not least, Erle Stanley Gardner. DSM, published twice a month and equally thick at 144 pages, has stories from their own stable of authors. DD, published twice a month with 128 pages an issue, offers a roll call of Black Mask authors – Erle Stanley Gardner, Fred Nebel, Carroll John Daly and J. Paul Suter among them in addition to some writers exclusive to DD.

More pages. More variety. And here’s the real kicker, the price. DFW is 10 cents an issue for 144 pages. DD is 10 cents for 128 pages. DSM is 15 cents for its 144 pages. I can buy two issues of DFW or DD for the price of one issue of Black Mask.

I think we’ve found our smoking gun.

PS:

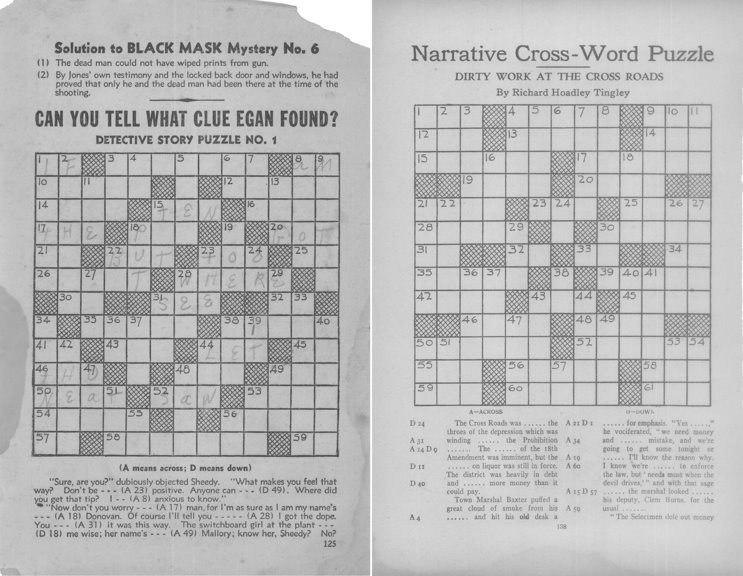

If you think Black Mask wasn’t aware of the competition, take a look at the puzzle. Left, Black Mask. Right, Detective Fiction Weekly. DFW’s started in 1931, Black Mask’s in May 1933.

PPS: If you think this issue’s quality was out of the ordinary for this time, take a look at these reviews of the October 1933, May 1934 and January 1935 issues.

Next week: Let Darkness Fall

True, in 1930 Hammett stopped publishing in BLACK MASK and moved on to the higher paying slicks. But he also started writing for Hollywood and the movie industry paid big money to screenwriters. I’ve read somewhere that Joe Shaw, in an attempt to get Hammett back to writing for BLACK MASK, sent him a check for $500 as payment in advance for stories. Hammett returned it because Hollywood was paying far more money than Shaw. Also Hammett was getting quite a bit of money eventually for the rights to The Thin Man series.

Today we might look at a dime and say, “so what if the magazine cost twice that at 20 cents. No big deal”. But in 1933 the value of 20 cents in today’s money would be $4.53. While 10 cents for DIME DETECTIVE would be worth only half that at $2.26.

A big difference during the depression.

This is an excellent series Sai, I hope you continue on through the Popular Publication years. Ken White, the editor, always impressed me during the forties.

Thanks Walker. Good to know at least one person is reading these articles.

Yeah, the extra dime for an issue of Black Mask would have been a big deal back in the 1930s. You could get a meal for a dime back then.

I shall be looking forward to next part, you do great work Sai

Thanks, Barry. Now it’s two readers for sure I’ll be putting in extra effort 🙂

Hi Sai, am loving your analysis here! Very well written. Just a small correction. Clayton went bankrupt and sold titles off in 1933, not 1930

Thanks for catching that, Sheila. I had a senior moment there, having published an article on that very topic recently 🙂