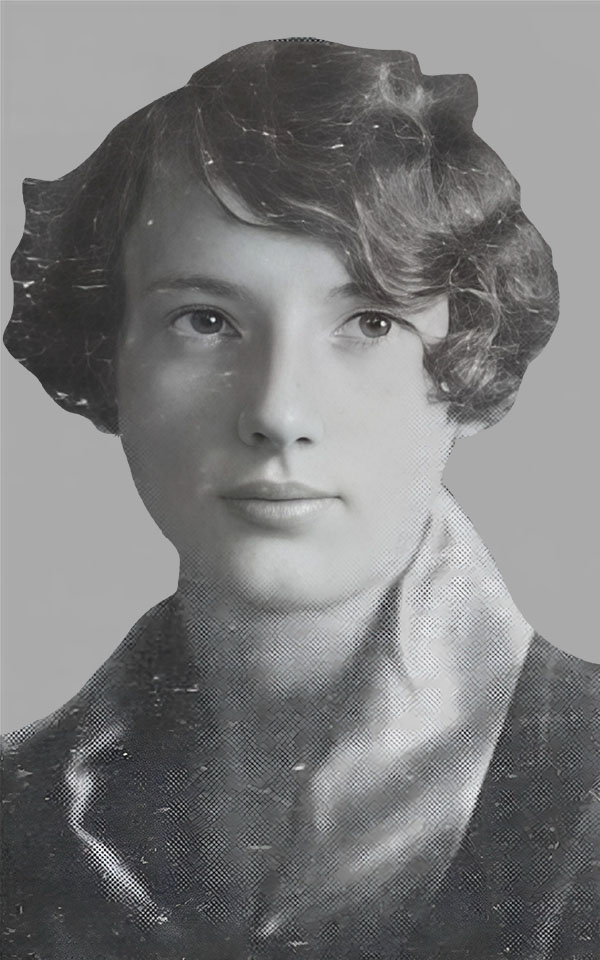

Last week, we took in an issue at the peak of Joe Shaw’s reign; it delivered hard-boiled at it’s peak but circulation didn’t improve. The publisher brought in a new editor, Fanny Ellsworth. She wasn’t afraid to tinker with Shaw’s formula and introduced darkness into Black Mask’s fiction. Did it work?

Fanny Louise Ellsworth (1905-1983) was the only child of banker Jesse F. Ellsworth and homemaker Martha Kelly. She attended Barnard College, graduating in 1926. She worked as a proof-reader before joining W. M. Clayton’s pulp magazine chain in 1928. There she worked as an assistant editor before taking over the editorial reins of Ranch Romances in 1929. Ranch Romances was a pulp that combined the romance and western genres successfully and ended up being the longest running pulp. Warner had bought the title in 1930 1933 when the Clayton chain went bankrupt, and acquired Fanny’s editorial services along with the title.

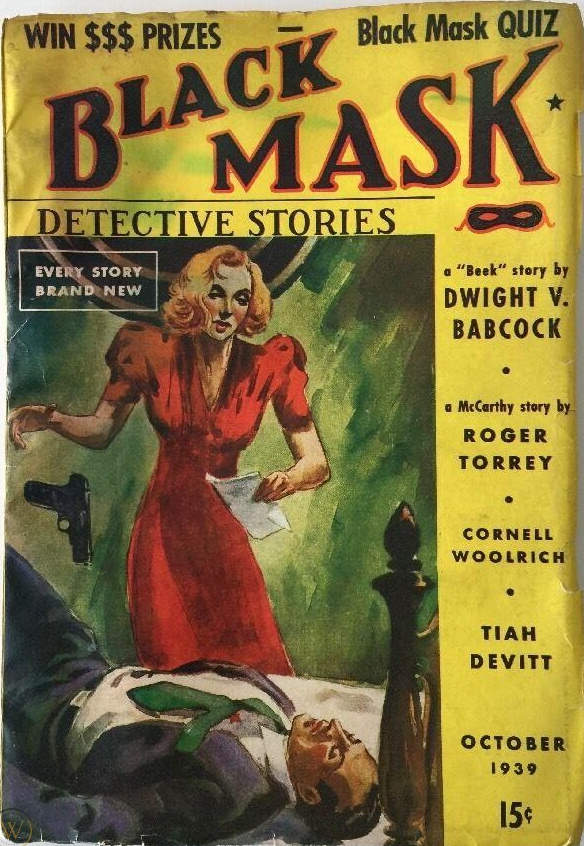

Ellsworth was editing a non-romance magazine for the first time. But her editorial choices didn’t show any hint of first-time nerves. She changed the cover design and the content but not the well-recognized logo.

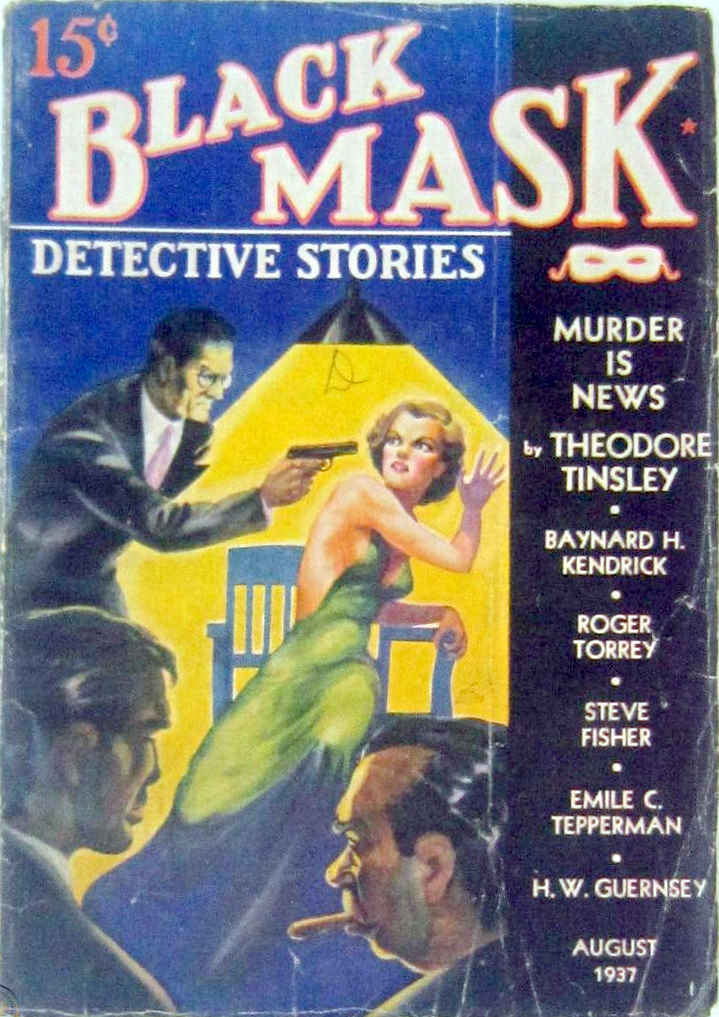

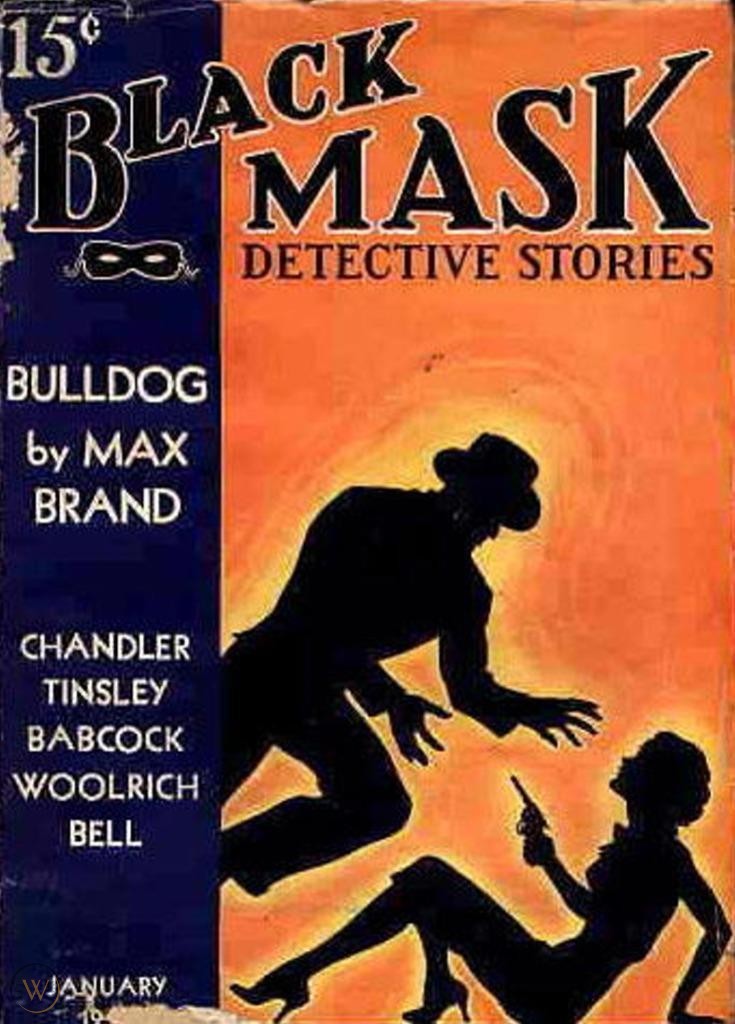

The Art

The covers would have been a shock to readers who picked up the January 1937 issue. For a start, the background was orange instead of the usual white, the illustration only occupied two-thirds of the usual space and it showed a woman being menaced. Women, who had only occasionally appeared on the covers in Shaw’s decade, would be present on the covers of over eighty percent of issues she edited. Not every cover had guns, but there was always a weapon of some kind. Author’s names appeared on the cover; story titles were usually omitted. Interior illustrations were still done exclusively by Arthur Rodman Bowker.

The beginnings of Noir

The contents, too, would have surprised readers. Suspense, of a variety that Cornell Woolrich did best, was added. Woolrich became a frequent contributor, as did Steve Fisher, a writer who wrote from the point of view of criminals and the criminally insane.

Ellsworth balanced noir with humor and variety. A couple of issues later, Frank Gruber added humor with his stories of Oliver Quade, the encyclopedia salesman who detected his way out of crimes he got stuck in the middle of. Baynard Kendrick, famous for his blind detective Duncan McLain, created a new series for Black Mask. With stories like Fisher’s “You’ll Always Remember Me” and Woolrich’s If the Dead Could Talk, there’s a good argument to be made that Fanny Ellsworth’s editorial choices laid the foundation for crime noir to emerge as a significant story and movie genre.

Many authors left Black Mask after Shaw’s departure; among them Raymond Chandler and Fred Nebel. But Ellsworth was able to convince John Carroll Daly to return, and Shaw himself sold Ellsworth a story. Death rides Double, attributed to Mark Harper, Shaw’s pseudonym, appeared in the October 1939 issue. World War 2 started to intrude on the magazine, the occasional story set in war conditions appeared.

In January 1940, the price was increased to 20 cents and the page count increased by 16. None of this made a difference. Circulation steadily declined to 45,000 copies. The magazine was becoming very unprofitable; Warner cut his losses and sold it to Popular Publications.

Ellsworth remained with Warner as editor of Ranch Romances. She followed the magazine when it was sold to Ned L. Pine’s Thrilling Group in 1950 and remained its editor till 1953. Then she quit the publishing industry and returned to scholarship. She studied Turkish history and culture, earning her doctorate from Columbia University in 1968, and authored multiple books on Turkey before her death.

Next week: Let the darkness surround you in a review of an Ellsworth-era Black Mask

I’ve often felt that the Fanny Ellsworth years suffered in comparison to the Joseph Shaw era. I also did not particularly like the cover art during her time as editor. But, as you point out, she did publish authors that Shaw would have rejected. Cornell Woolrich, Frank Gruber, and Steve Fisher were published by Ellsworth.

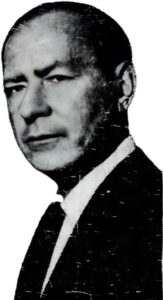

Shaw seemed to me to lack a sense of humor and sometimes I thought he encouraged his authors to be *too* hard boiled though he did publish one of the funniest hard boiled stories I’ve read, “The Devil Suit”.

Noir and suspense were not Shaw’s strong points either.

I think Shaw was a victim of his own success. He developed great authors, paid them well and they responded by giving him a steady diet of hard boiled fiction. The reading public, though, wanted variety.

Ellsworth gave them what they wanted, but had to deal with a smaller budget. She economized on covers, using lesser known artists. Unfortunately for her, the competition—Dime Detective, Detective Fiction Weekly and Detective Story Magazine—were doing the same thing at a lower price point and with better covers. The authors that had left Black Mask were appearing in those magazines.

Hard to do well in those circumstances.

Another great article Sai, looking forward to the next one.

Thanks, Barry.