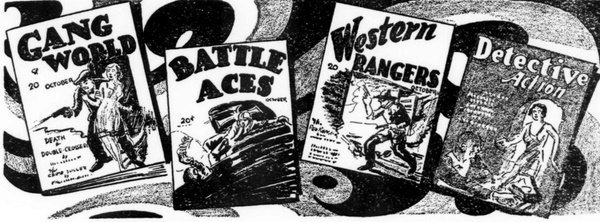

Last week we saw how the competition was hurting Black Mask during Fanny Ellsworth’s editorial reign. And hinted that it might need a bigger backer. That backer was Popular Publications, a phenomenon created by Harry Steeger and Harold Goldsmith, who had started with four titles and a combined print run of 400,000 copies. While Battle Aces had only one-fifth of its copies returned and showed a profit from the first issue, the other three titles had about half their copies returned. From these modest beginnings grew a pulp empire that was selling a million and a half copies per month in 1939.

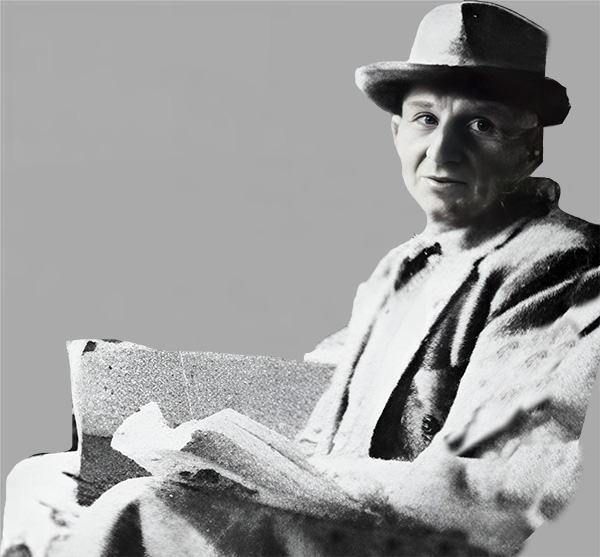

Kenneth Sheldon White(1905-1964) was one of the earliest editorial assistants that Steeger hired. Son of noted explorer, adventurer, journalist and magazine editor Trumbull White, Kenneth had completed his A.B from the University of Michigan in 1930. While at college, White was a member of the Comedy Club. After college, he did I don’t know what for two years before being hired by Steeger in 1932 or thereabouts. He became one of Steeger’s trusted editors.

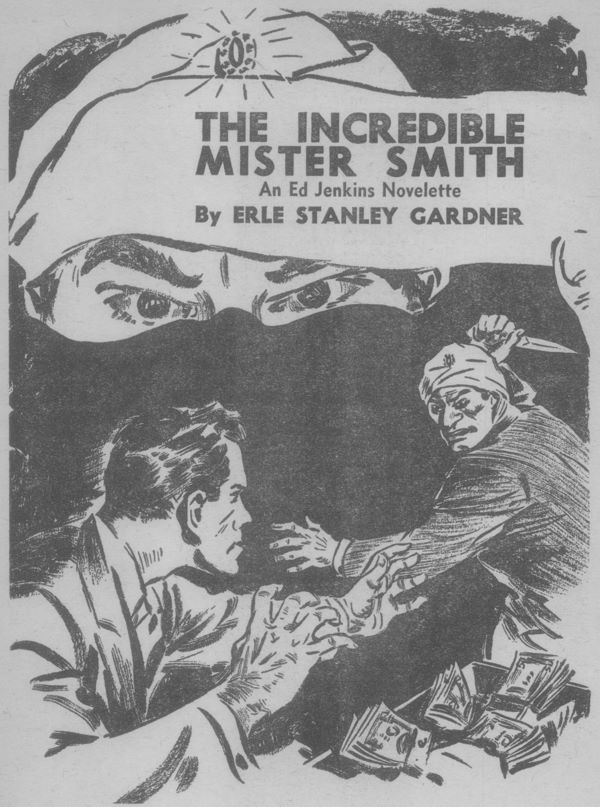

Dime Detective, launched in 1931 with Steeger himself as editor, was transferred to White in 1936. Steeger had lured Black Mask’s top authors with a penny a word hike over their Black Mask rates and got them to create new series for him. Fred Nebel created Cardigan and Sgt. Brinkhaus and John Carroll Daly told stories of Vee Brown and Marty Day while Erle Stanley Gardner tried a variety of characters. Black Mask regulars like George Harmon Coxe, J. Paul Suter and Roger Torrey also made appearances in Dime Detective.

Dime Detective was Popular’s first big success and very profitable for the company. To be trusted with running it meant White had the full confidence of Harry Steeger. White justified it by bringing in Cornell Woolrich and Raymond Chandler. He also introduced D. L. Champion’s bitterly funny Inspector Allhoff and T. T. Flynn’s Mr. Maddox, a racetrack detective. Both series were big hits. Dime Detective was beating Black Mask at its own game.

Authors

When Popular bought Black Mask in 1940, it was natural that Steeger appointed White as editor. Steeger picked out covers while White picked authors. New series bloomed in Black Mask like poppies in spring, and most lasted as long. As successful authors like Chandler and Woolrich departed for the more profitable pastures of slick magazines, books and in some cases the siren lure of Hollywood, Ken White kept bringing in replacements. Robert Reeves, C. P. Donnel Jr., Cleve F. Adams, Dale Clark and Merle Constiner were part of a very capable team that filled out the magazine’s 128 pages.

Down to a fine art

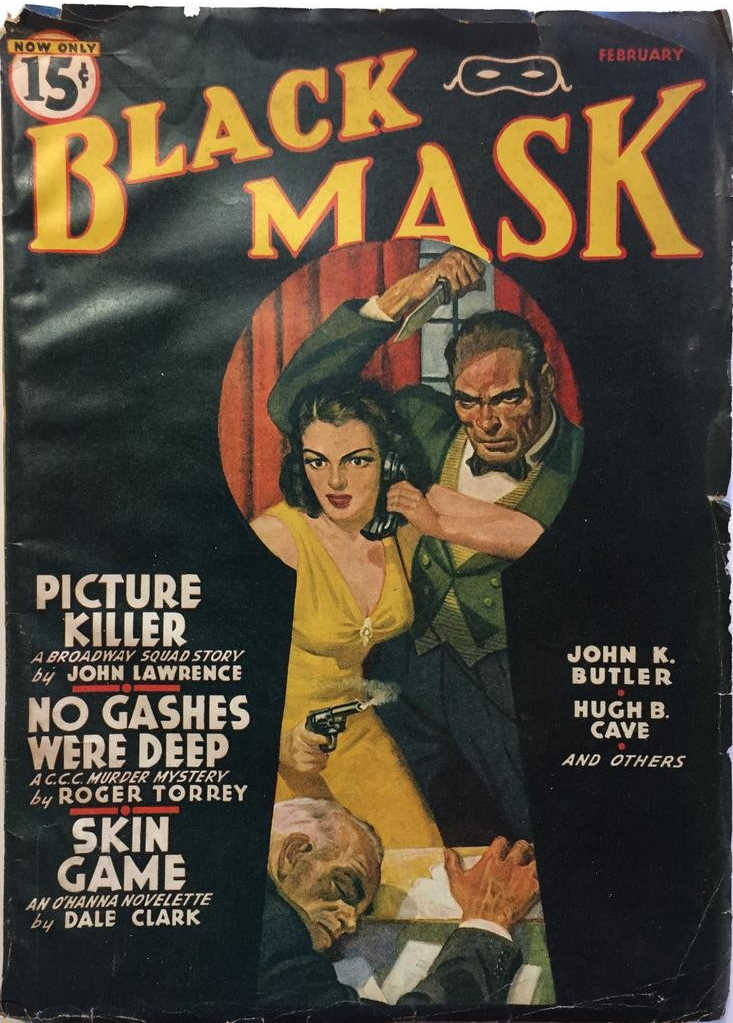

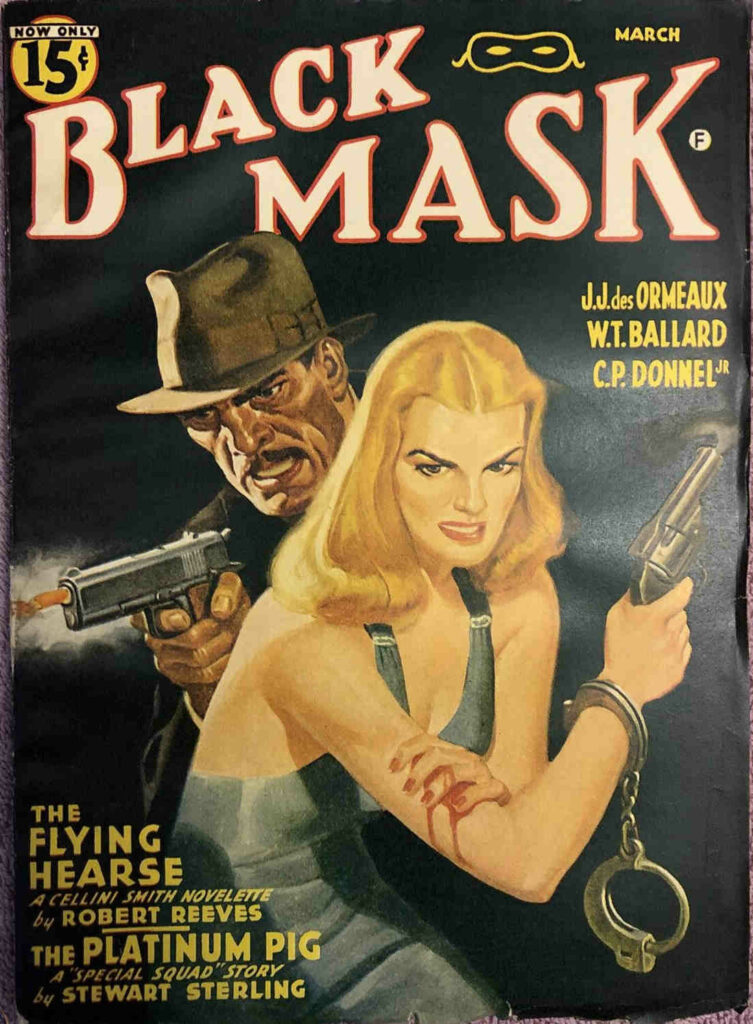

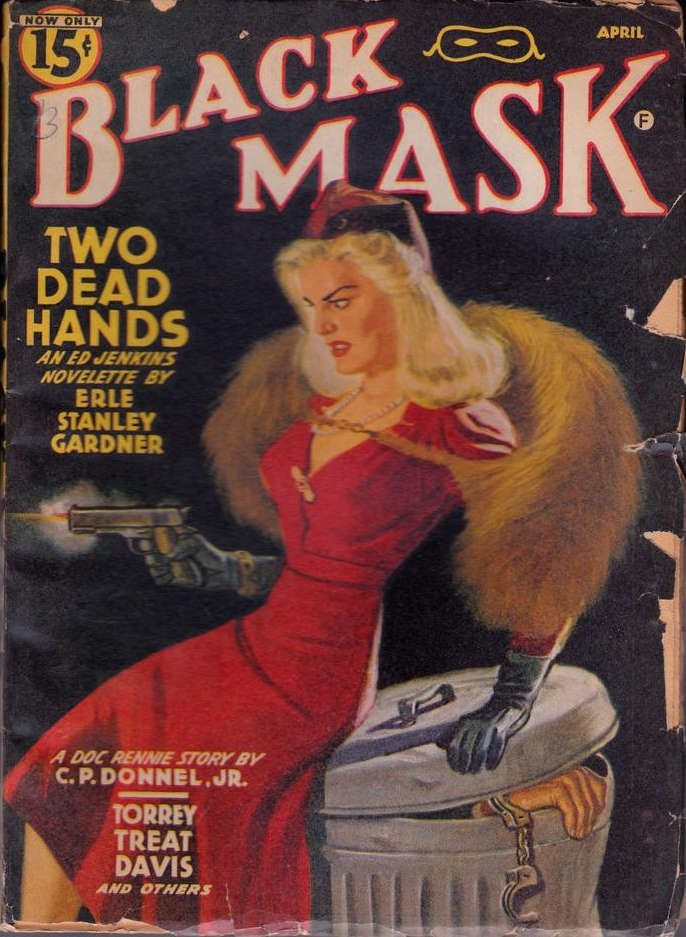

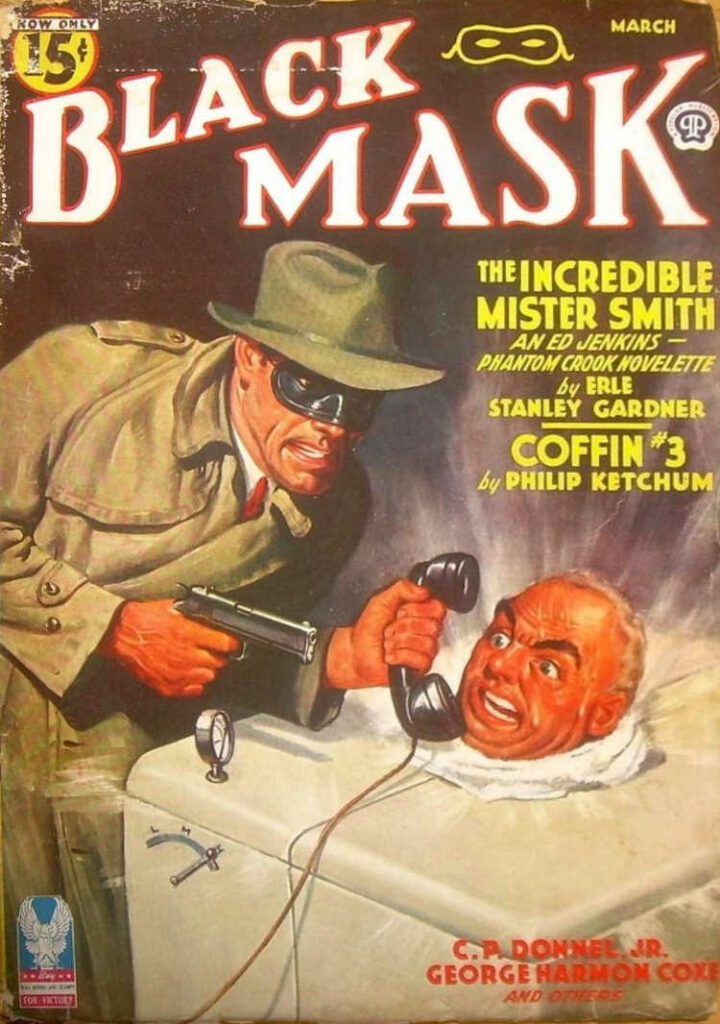

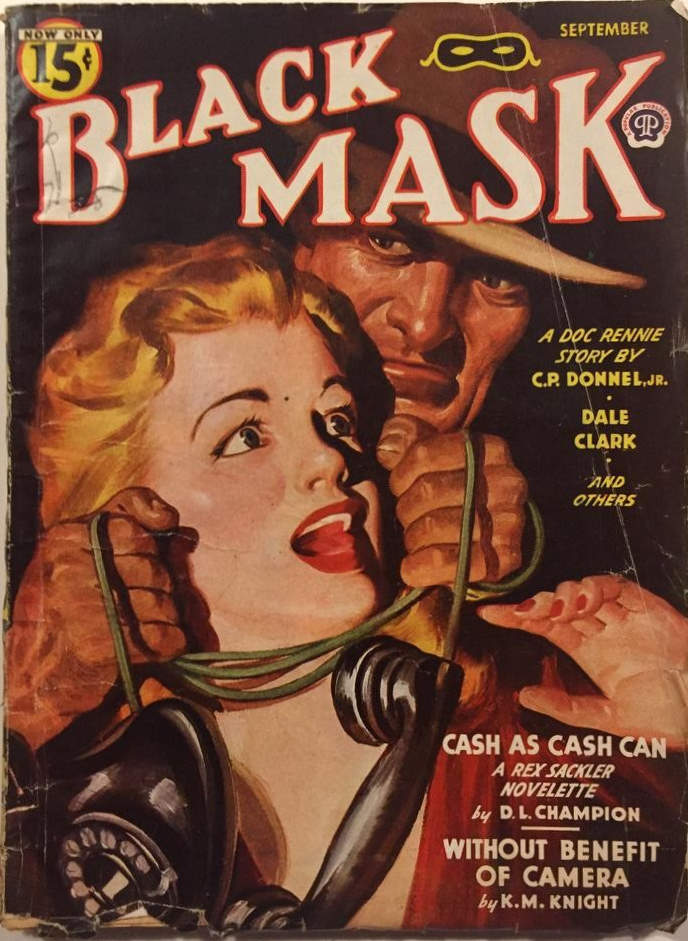

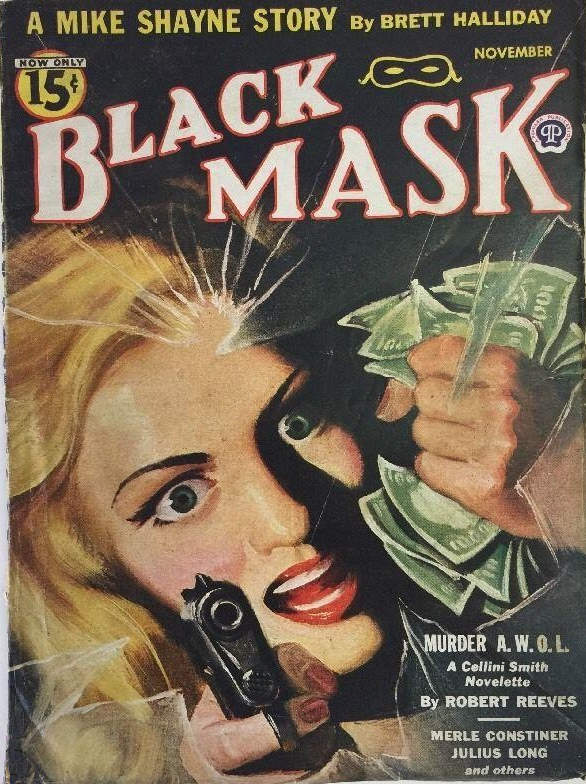

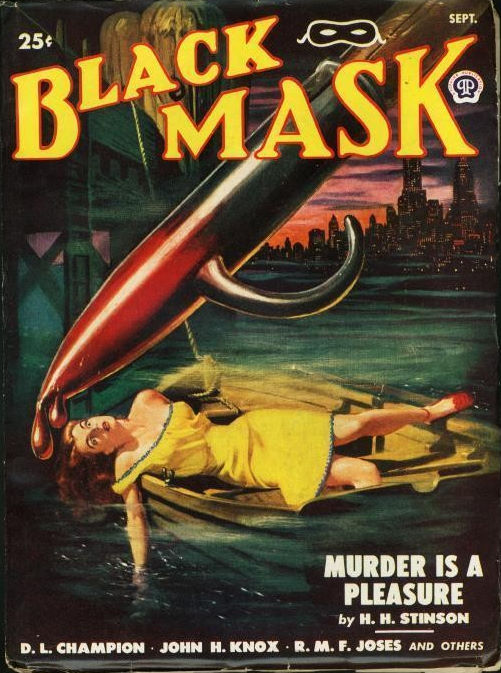

Where White knew how to pick authors, Steeger had firm opinions about cover art and color palettes. The artists from the Ellsworth era were replaced by top-flight artists from Popular’s stable. Where Schlaikjer was the artist of the 1930s, Rafael De Soto was the artist of the 1940s Mask. Covers had black backgrounds, allowing primary colors like red and yellow to pop.

The people on the covers were, in contrast to Shaw’s era, expressive in their facial expressions and their body postures. Extreme close-up perspectives, unusual angles and the use of situational framing devices like keyholes, prison bars, gratings, broken windows and portholes drew reader attention on the newsstand. As did the occasional slightly surreal cover like the one on the March 1943 issue that showed a masked man holding a gun and phone to the head of a sweating man who’s stuck inside a boiler turned to high.

Violence against women, missing in the Shaw era and discreetly hinted at in Ellsworth’s time, was a frequent theme. To be fair to Steeger, covers featured women with guns drawn about as frequently as they showed them being menaced.

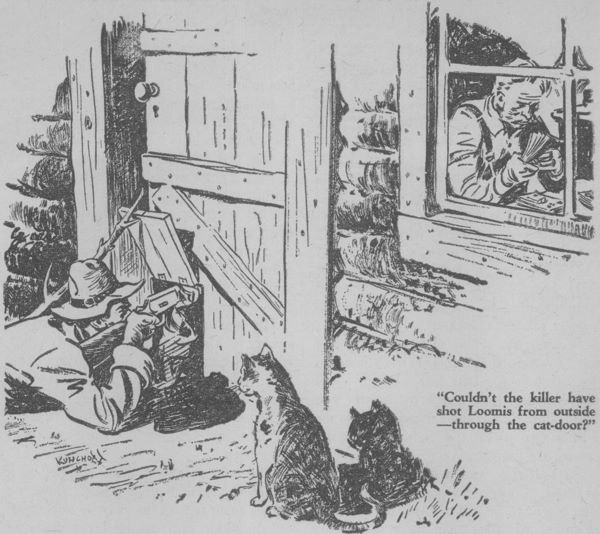

The interior illustrations were now done by Pete Kuhlhoff, whose style suited the less hard-boiled, more relaxed stories in Black Mask. Kuhlhoff’s work was more detailed with expressive people, curvy lines and full blacks replacing Bowker’s grim characters drawn with straight lines and gray shades in the 1930s. The drawings were now less hard-boiled and darker, like the stories themselves.

The War

Though everyone involved was giving their best, external factors were driving the pulps out of business. In World War 2, the industry was hit with paper restrictions, rising prices and the loss of their best customers who shipped overseas or to training camps. Black Mask tried to maintain the cover price of 15 cents, but something had to give. The page count dropped, first from 128 to 112 sometime in 1943 and then to 96 pages with the Sept 1944 issue. They tried to compensate with a tinier font that is much harder to read than the previous issues. Black Mask switched to bi-monthly publication with the March 1943 issue.

Aftermath

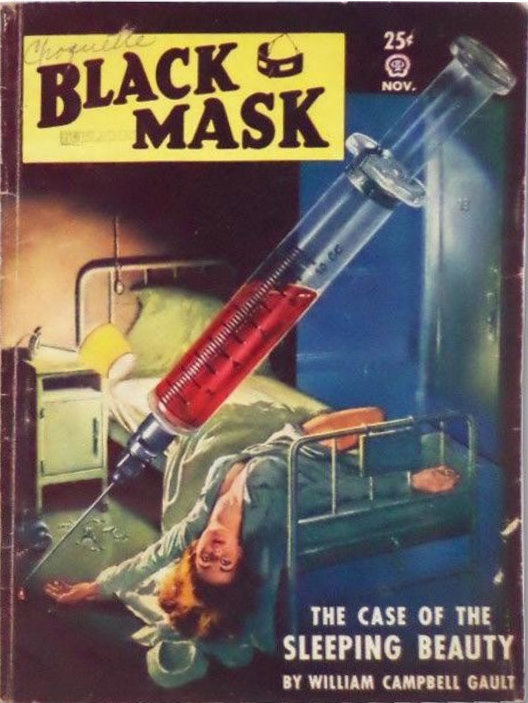

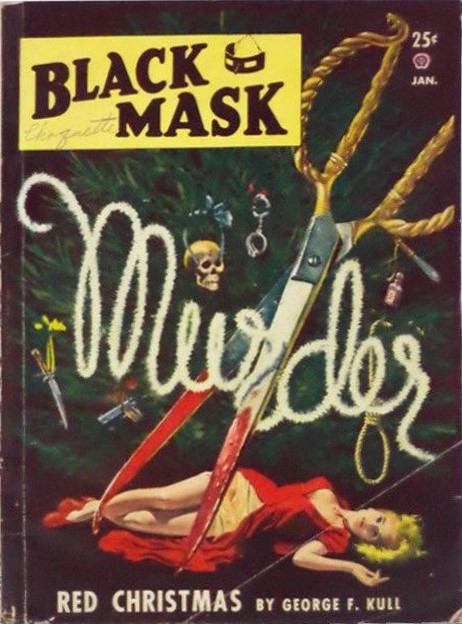

A few years later, in May 1947, White tried to reboot the magazine. 32 pages were added. The contents were a little more hard-boiled. Authors like John D. MacDonald, Bruno Fischer, Richard Deming, William Campbell Gault and Frederic Brown made their debuts. White’s taste in crime fiction was excellent. What was missing was a real headliner, one who was already famous.

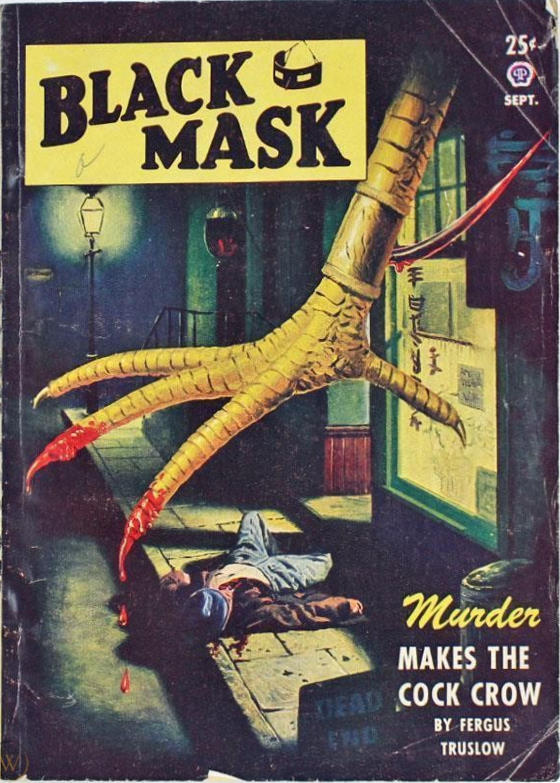

In the new covers the means of death were highlighted on the cover – a rooster’s claws, the electric chair, a hammer, a syringe etc. and the dying person was in the background. While this made for dramatic covers, the quirkiness of De Soto’s covers disappeared. Something had changed about the covers. They no longer looked as bright or glossy. It could have been the grade of paper, the inks or the printing process. Either way, the covers didn’t grab your attention as much as they used to.

A single illustrator was no longer doing the interiors. Uncredited artists (another change) used a variety of styles, one for each story. This was in line with other Popular Publication pulps.

The price increased to 25 cents. If you ask me, it was a bargain. Manhunt, launched six years later, offered 144 digest sized pages at the same price. Black Mask, printed in the pulp format, was giving the reader the equivalent of nearly one and a half Manhunt issues in one issue. It didn’t work. Sometimes you have the right idea at the wrong time.

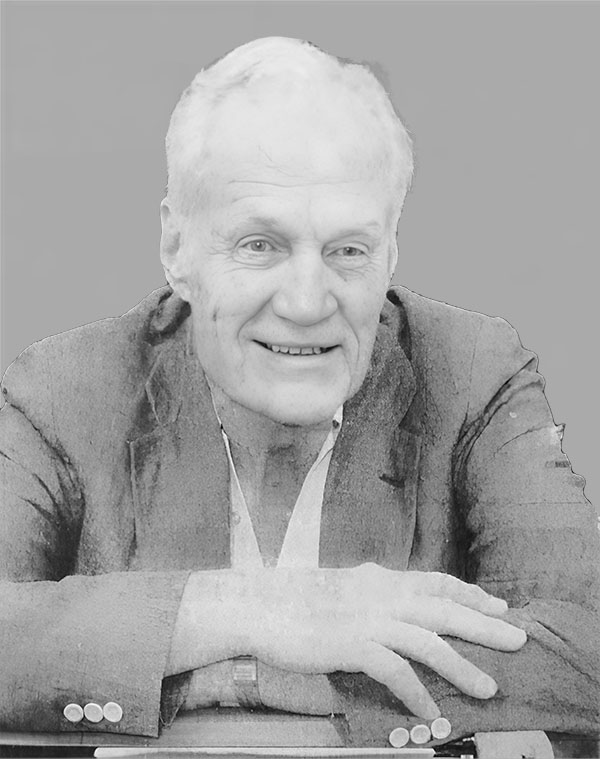

In 1949 White and Popular Publications parted ways. He went to Esquire, where he was an assistant editor and then became fiction editor. He left Esquire to create his own literary agency and represented notable science fiction authors like H. Beam Piper before his unexpectedly early death in 1964.

Coming up: Reviews of two issues under White’s direction

Thanks for this excellent essay on Black Mask during the 1940’s when Popular Publications took over. I’ve always thought that Ken White was just what Black Mask needed during the forties. Joe Shaw might have been too tough, too hard boiled and as a result the stories started to sound similar.

Ken White encouraged the authors to be less hard boiled and use more humor and complicated plots. Many of the stories were quite long, near 20,000 words and thus allowed more room for characterization and the sometimes insane plot developments.

Joe Shaw had a massive influence by encouraging the hard boiled style as written by Hammett but I’ve found myself liking the Ken White years even more than the Shaw issues in the 1930’s. I’m sure most readers would disagree and consider such a statement sacrilege. I guess it’s the humor and crazy plots and characters that appeal to me.