The Wikipedia article on Richard McKenna covers his life and fiction reasonably well. But if you’re feeling lazy, I asked ChatGPT to summarize it for you.

Richard McKenna (1913–1964) was an American naval officer and author known for his acclaimed debut novel, The Sand Pebbles(1962). Born in Idaho, McKenna served in the U.S. Navy for over two decades. The Sand Pebbles explores the life of a sailor on a U.S. gunboat in China during the turbulent 1920s. The novel garnered widespread praise and was later adapted into a successful film. Unfortunately, McKenna’s promising literary career was cut short by his untimely death in 1964. Despite a limited body of work, his fiction remains well-thought of today.

This article of his, reflecting on how he became a writer, was originally published in The Texas Quarterly, Winter 1963 as Journey With a Little Man.

IF I HAVE LEARNED ANYTHING IN THE PROCESS OF BECOMING A PROFESSIONAL writer, it is that there are as many ways of becoming a writer as there are writers.

I am going to talk only about the way that worked for me. The thought of becoming a writer first came to me as an occasional idle fancy during World War II. It did not become a firm decision until about 1950. Then I planned it rather carefully.

I planned first to get a formal education and then to serve my writing apprenticeship in science fiction. That field pays poorly, so I thought I would not meet much skilled competition. It would also allow me to indulge the very great interest I had in all areas of science. My plan became my excuse for taking far more science courses than my major in English Literature would conventionally accommodate.

Often on my way through school I was tempted to give up my plan. I read everything and listened to everything with a perpetual “What if?” before me. Many answers which suggested themselves fascinated me. By each science in turn I was tempted to forego writing and take to asking “What if?” directly of nature. It seemed to me then and does still that science is as much a creative activity as art. Both are concerned with discovery and fabrication. Science is the art of the intellect.

What held me back each time was the conviction that only as a writer would I remain free to range across the whole of human experience and to mix intellect with feeling. I wanted to present new and fascinating ideas from science in the form of stories. I always assumed that when the time came to write the stories I would find it as simple a matter as writing term papers. Seldom have I been more wrong.

I had one experience in a science course which, if I had understood it fully, might have spared me much anguish when I began writing. It was an experiment in a psychology lab which took me through what I now consider to be a learning process of the same kind as learning creative writing. It is worth recounting in some detail.

That morning in class the instructor had told us that between any conscious intention and the completed act lies an apparatus of nerves and primitive brain centers not under control of the conscious mind. I understood and accepted the statement. The lab was in the afternoon. It was a fine summer day and several of the girls came to the lab barefoot. The lab instructor formed us into teams of two, and one of the barefoot girls fell to me as partner. She was to be the experimenter and I the subject. My task was to trace a pencil over a large five-pointed star printed on a sheet of paper while I saw my hand and the star only in a mirror. The girl would time me and record how often and how widely my pencil strayed from the printed line.

I always tried to do well in that psych lab. I think I wanted to prove that my reflexes had not slowed down. That day in particular I wanted to do well. While we waited for the signal to begin, I thought out carefully the principles of mirror- reversal. I was going to use my knowledge of optics and geometry to give me an advantage over the other subjects. The girl smiled what I took to be encouragement at me. We were facing each other across a table and all around the large room other couples were similarly awaiting the signal.

“Go!” the instructor said.

The girl clicked her stopwatch. My pencil went wildly off. I paused and thought quickly again through the geometry. When I knew exactly how my hand should move, I so moved it. Again it went skating awry with a will all its own. That happened again and again as I tried to reason my way through and to make my hand obey me. I felt a most peculiar dismayed frustration at the disobedience of my hand. It began to seem like an entity separate from myself. It would rush clear off the paper. If only the girl had not been there I could have cursed it. All around me the other subjects were finishing their first trial. I knew I was sweating and red-faced. The girl was plainly sorry for me, and that made it worse. I was her team and I was failing her.

Finally, in despair, I simply went at it by trial and error. That was not much better. I see-sawed painfully along. When I had to change direction my whole arm would freeze. I would will it to move and it would not. I could only start the pencil tracing again by moving my whole body from the waist. I was the last one in the class to finish the first trial and my trace was eleven times longer than the line I was trying to follow. I was ashamed to look at the girl.

I did better on succeeding trials. I found I could set up a random tremor in the pencil point and somehow simply wish it along in the right direction. I began feeling better and on each trial the tremor became less pronounced. At the end of the period the girl gave me a difficult pattern to trace, a complex affair of straight and curved lines. I yawed wildly off when I began it, but I did not call upon any optics or geometry. I just steadied on the course and wished my way on around it and my score on it was one of the best in the class.

When I wrote up the experiment I said it demonstrated that the neural complex below the level of conscious awareness can only be trained to a new mode of action by trial and error. If a general principle is involved the complex will, with enough trials, learn that also and be able to apply it in a new situation. The conscious mind may already know the principle perfectly and still be unable to apply it until it is also learned, slowly and painfully, by the unconscious part.

I should have written “unconscious partner.” I should have pondered the implications of that experience more deeply than I did.

When I finished school I married, with a clear understanding between my wife and me that I was going to become a writer, and I settled in to write. My attitude was very matter-of-fact. I was going to set words end to end as methodically as masons lay bricks end to end. I studied books and articles about writing and abstracted from them all a list of rules by which to write. Then I sat down at the dining room table to apply what I knew.

I found I could not. The words simply would not come. With all those rules in my mind I was like the fabled centipede who could not run for worrying which leg came after which. What little I wrote had about as much life in it as a brick wall.

I scorned it myself. However, when I laid aside the rules, the writing went the opposite way. What was planned to be a neat 5,000 words would explode to 30,000 and leave me feeling like the sorcerer’s apprentice.

The writing I did the second way pleased me too much. When I would try to apply those rules in rewriting, I felt distinctly that I was maiming living literature in favor of dead rulebooks. I applied them rather too gently, as I know now. I would send beautiful manuscripts fluttering off to the marketplace. They would come creeping back to me out of the dust and heat with printed rejection slips clamped in their ugly beaks.

That went on for more than a year. I became increasingly grim. I refused to believe that I could not write. I felt intolerably exasperated at my powerlessness to do as I willed. My plan had gone wrong, somehow. Originally I had meant to live in the Nevada desert, alone except for books, and to write there. I will not expand on the painful months during which the conviction grew in me that I would have to go to the desert. At last I could bear it no longer, and I proposed to my wife a trial separation both from her and from Chapel Hill.

I stood at that moment in the greatest danger of my life. I know now that no writer can have a better wife than I have nor a better place in which to write than Chapel Hill, where I found her. What I really had to have is what I have since come to call “creative isolation.” I would have found that in the desert and misinterpreted it. But I will always be grateful that I gained it in a much less drastic way.

I took an office downtown. It had no telephone. Neither my wife nor anyone else was ever to come there and disturb me. Every morning before eight o’clock I would lock myself in with a thermos of coffee and a sandwich. I would not come out again until after five o’clock. I did that seven days a week.

From the first day, much of my anguish left me. I recognized it as the same I had felt in the psychology lab. My confidence and drive came back. I could read stories that were the best I could do six months before and see flaws all through them. I realized that all the while I had thought I was stopped cold I had really been making progress. I was midway in just such a process of unconscious learning as tracing that star had been.

Learning to write creatively is a process of training the unconscious, I decided. We all have an unconscious personality component, a silent partner in all we think we do alone. In some learning situations that silent partner can lag far behind his conscious partner. Mirror-drawing is one such situation and learning to write creatively is another.

That insight into my work saved me from a disastrous mistake in the other part of my life. It remained to act upon it in a way which would forward my work. Isolation was a necessary but not a sufficient condition. Fortunately, the others were easier to discover.

The first step was to attain and hold what I came to call the writing mood.”

I had never experienced it before I began working in that office. It was a kind of inner excitement, a bit like waiting for a curtain to rise upon something unknown and wonderful. I learned to evoke it in various ways: wandering idly about the office and trying not to think at all; sitting at my desk toying with my pencil and a blank sheet of paper; reading poetry aloud to myself. At first it always took me several hours to evoke it and distressingly often I could not evoke it all day long.

I learned not to fret about that. The one certain way not to attain the mood was to grasp for it with grim resolution. I had to not-care before it would come. Once attained, it was most precarious. A knock on my door and the necessity to speak even a few words would banish it for hours. A trip to the barbershop would destroy a whole day for me. Sometimes I became quite shaggy while I strove to finish a short story and I could almost envy a bald man.

I wrote only when I was in the mood. Certain strange aspects of it came to my attention. I would write half a page and realize with a start that an hour or more had passed in what seemed like a few minutes. An observer would no doubt have seen me sitting frozen for minutes at a time, but I never had the sense of it. Often I would be up and away from my desk before I realized that I was pacing. At first, with the lingering conviction that one would never get a brick wall built that way, I would sit resolutely down again. That always broke the mood. But if I simply went on pacing I would before long find myself back at my desk and writing with no memory of having first willed it.

On days when I could not reach the mood I would do research for my stories. I read through many a science textbook, making notes and stopping to reflect and feeling the same pleasant excitement as when I was in school. That was a different excitement, more of an intellectual excitement. The writing mood was visceral; I could feel it vaguely across my midriff. Sometimes I would try to study Maugham or Kipling or some other master of the short story to learn technique. I could not deal with them as with the textbooks. After a paragraph or two I would be swept away by the story and not catch myself shirking duty until after several pages. The trouble, and the familiar frustration, I knew how to explain to myself.

By then, strictly for my own purposes, I had postulated an unconscious part of myself which I personified and named “the little man in the sub-basement.” It was a game and I played it as children do, only half-believing and half aware in delightful balance that it was only make-believe. I was not being scientific; I was simply trying very hard to learn to write. I never thought then that someday I would talk about it publicly. I find now, however, that I cannot tell how I became a professional writer without giving the little man his share of blame and credit. He was the one who was shirking duty when we read Maugham together.

Whatever I wrote when I was “in the mood” was better than I had done before. I began getting a few scrawled words and initials on the printed rejection slips. Then I began getting handwritten notes of rejection. Six months after I began work in my office, just as the Christmas holidays of 1958 set in, I received a formal letter of rejection. It pushed me across what I now consider to be the barrier between amateur and professional writing.

The rejected manuscript ran to 14,000 words. The editor told me that I had story enough for only 7,000 words. If I could compress it to that, he would be willing to read it again. It was not a promise of a sale. But it was the first expression of interest I had gotten in almost two years of steady work and it energized me powerfully.

I reviewed all my rules for cutting wordage and over the holidays I squeezed lifeblood out of that story in four rewrites. Each night I would count up the words I had eliminated that day. At first they were hundreds. Then they dwindled to tens. It grew progressively more painful. At the last I was pulling out single words and phrases that shrieked like mandrakes. But I told myself that it was the little man’s pain, not mine, and he could learn only by suffering. With rules like razors I vivisected him unmercifully, cut the manuscript exactly in half, and sent it off again.

The little man should have hated me for it, but he did not. The day after his ordeal ended he handed up to me complete in one session a new story of only 3,500 words, shorter by half than anything I had done before. To this day I wonder whether he was not drawing in it a portrait of himself. The opening line read: “You can’t just die; you got to do it by the book,” and it was the little man speaking, all right.

That story, entitled Casey Agonistes, sold at once and became my first published work. In his letter of acceptance the editor called it “admirably terse” and I could feel the little man glow when we read that. The editor went on to ask that the story be expanded by several hundred words. I felt the little man glower. We expanded it by about fifty words and begrudged every one of them.

Casey Agonistes moved me from amateur to professional. The distinction is hard to define. Its salient characteristic, to me at that time and in my own terms, was that the little man had finally grasped the idea of learning. He began learning of his own volition. I found I could no longer read a short story purely for entertainment even if I wished to. I would note the technique as I went along and it seemed an added dimension to the entertainment. I wonder now whether editors do not develop an intuition that tells them when a writer has crossed that invisible line and become professional. Only then, when it can be used effectively, do they offer help. In any case, 1958 became for me a year of rapid unfolding.

The story I had cut in half also sold. I began selling stories regularly. Editors would ask for revisions and I would make them and learn by doing so. A literary agent named Rogers Terrill heard about me and Casey at a cocktail party and remarked casually, “Sounds like that guy might have a book in him.” A mutual friend brought us together in correspondence. Terrill did not want to handle science fiction. He made a deal between us contingent upon my writing a sample straight fiction short story from which he could judge my potentiality. I set the little man searching for a suitable story idea.

Also through Casey I was invited to the annual science fiction writers conference in June at Milford, Pennsylvania. It is restricted to professionals. I accepted and was hard put to get my sample short story written and off to Rogers Terrill before meeting him in New York after the conference for an interview. All through those days I lived in a sense of portent. My wife went to Milford with me and all night on the bus we did not sleep a wink.

At Milford I met writers who for years had been only names to me. They treated me as another professional, without the slightest condescension. I wish I had time today to describe Milford more fully. The writers work in isolation during the year and come from many states to gather at Milford in June. It is something like a trappers rendezvous in the old fur-trading days. Magazine and book editors attend; sales are made, book contracts talked about, another year’s work planned. The work is strangely compounded of carnival and hard-headed practicality. The latter is the tone of the workshop, which takes up most of each day, and which had the greatest influence on me.

No one can be present in the workshop but the writers themselves, and each must have one or more stories in the pool. The stories are usually ones written during the year and which would not sell but which the writers are reluctant to scrap. For each, it seemed to me, the problem was how to suit the story to the mass-market without sacrifice of artistic integrity. And here were men and women who wrote for a precarious living at a few cents a word and who could see both requirements clearly without setting one above the other; persons who were working out a solution with all the resources of their pooled experience. I was very proud to be one of them. There was a rapport-quality to it. I felt distinctly upon me that “writing mood” which I had never before been able to attain in the presence of another human being.

We came down to New York in a daze. My wife walked with me to the interview with Rogers Terrill. She was going to leave me at the door. As a sailor I had known New York quite well, but now as we walked along it looked different. It loomed all around me, heavy with portent. As always, nameless people thronged along endlessly in both directions. Now they all had faces, strange faces. Now they were the people for whom I wished to write. As we approached the busiest comer it was with a shock of pleased surprise that I saw a familiar face. It was Dr. Bill Poteat, in whose philosophy classes at Chapel Hill I had probed more directly into the secret of existence than perhaps in any other. We talked for only a moment, but I went along strangely reassured, as if I had been granted a favorable omen.

I talked a long while with Rogers Terrill. He was a small man with a seamed face that could crinkle into a warmly infectious smile. He said he could sell my short story if I would revise it, and he asked me if I had any plans to write a novel. I said no, that I wanted to learn as much as I could by doing short stories before I thought about novels. He agreed, and I was encouraged to tell him the thought that had crystallized in me during those workshop sessions at Milford. I said I wanted to combine literary excellence with popular appeal, without sacrifice of either, no matter how relatively unproductive I might be of marketable manuscripts. Terrill jumped up and came smiling around his desk and we shook hands on that. The handshake was our contract.

I came home to Chapel Hill feeling that I had been through something very conclusive. I found that I could get more quickly into the writing mood each morning. It was much less vulnerable to distractions. Then I began hitting a new kind of block. I would start a short story and it would go well the first day and less well on each succeeding day until the words would stop altogether. The mood would be strongly on me and yet the words would not come. When I tried to write just anything, in order to bull through a first draft, my handwriting would go all awry. It would become large and awkward and trembly, as if I were writing with my left hand. The first time that happened I was frightened and I stopped work for that day.

Quite soon I discovered that if I would only start writing the story over from the beginning, my hand would be free and the words would come smoothly again. I would have to start a short story seven or eight times, each time getting a little further along with it, before I had a first draft. In terms of the game I was playing, it meant that something not apparent to me consciously went wrong along the way with those stories. The little man knew what was wrong and the only way he could remedy it was to force a new start. With each new start there were changes and sometimes, but not always, I thought I could see a reason for them. It made me feel floating and helpless and I would figuratively hold my breath until I had a complete first draft. Then, however, I would have it nailed down. I could rewrite straight through as often as I wished and with more confidence than I had ever had.

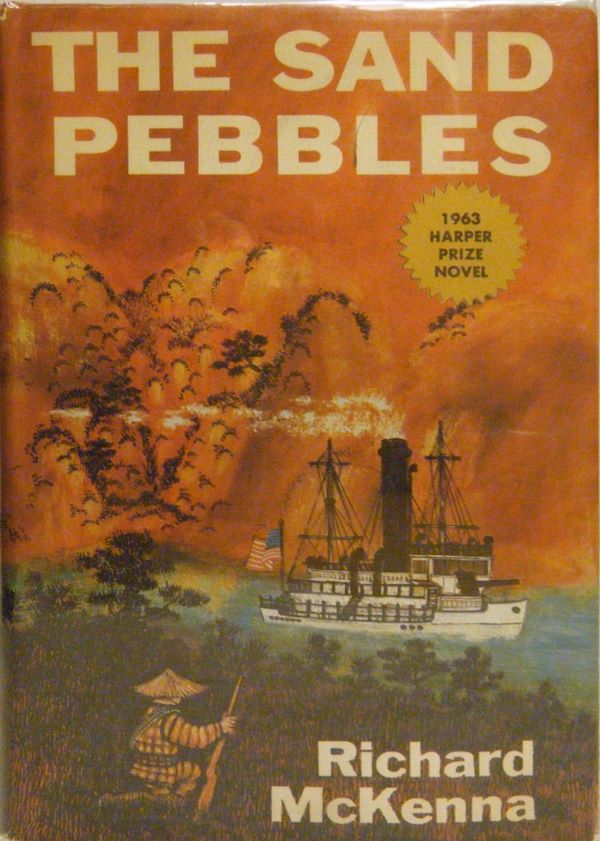

The sample short story I had written for Rog Terrill was based on a yarn I had heard in China as a boy. My story did not quite reach to that yarn, but it set the stage for it. So I wrote a second story with the same characters and setting, and again I fell short of the germinal yam. Rog sold both stories after I had made extensive revisions, but he began telling me that I really had a novel in that material. He urged me to write it. I was reluctant to take the plunge.

However, I developed a great urge to read books on China, any book on China. The dryest book on China would hold my interest. I said that I was going to mine that material for short stories. I wrote them and Rog sold them but in every letter he nudged me toward a novel. He said that with a few sample chapters and a synopsis he could get me a book contract. Thus I could be assured of publication before making the full investment of time and energy. By the end of 1958 he had persuaded me.

By June of 1959, in close consultation with Rog, I had written Part I of the novel at least six times. It ran well over a hundred pages. Rog arranged for some quick readings while I attended my second Milford conference. I had moved clear out of science fiction and into the men’s magazines, but they still welcomed me at Milford.

I went down to New York and spent a week reading files of old Chinese newspapers in the Public Library while Rog angled for a book contract. He tried three publishers and failed. Then he said I would have to rewrite. We talked over how I would do it, in the light of the editorial reactions.

Home in Chapel Hill, I seemed to lack the heart to go on with it. Probably in an effort to escape and with a kind of false and feverish zeal, I explored the Spanish- American War, oil tankers, and early nineteenth-century pirates. Nothing I wrote was much good. Sometime about September I developed an urge to read Hemingway.

I considered such capricious urges to be signals from the little man. For some reason he wanted to read Hemingway.

We had studied Hemingway before, but this was different. We stopped writing and read everything of Hemingway in print in a state of sustained, nonanalytical excitement. We came out of it with the concept of the “clean, well lighted story.”

I will not try to explain it. It is the little man’s concept, a matter of pure feeling, and the most he can do is grimace and point to “Big Two-hearted River.” The experience had the feeling of a change in kind, as with Casey Agonistes. Thereafter, in a manner impossible to convey, I wrote from a different posture, with a kind of spiritual body-English unknown to me until then. The first story I wrote from that posture, and very clumsily, sold to The Saturday Evening Post.

In the fall of that year, 1959, I had a chance to buy the house I now live in on Cobb Terrace. I bought it with misgivings. The down payment took the last of my navy savings and I was fearful of what economic insecurity might do to my writing. I would no longer be able to rent the office. But the house had an extra room which I could hedge about with the same tabus as my office and I gambled that my work habits had become dependable enough to stand the transfer. The last story I wrote in my office was the Post sale, and it furnished our new kitchen.

The Post sale eased my feelings of insecurity. I decided that I would stay on short stories until the house was paid for and I had a small cash reserve again before starting the long pull on the novel. For the next several years I was going to write primarily for money.

I stopped reading about China. I studied scores of Post stories and I tailored every line I wrote specifically for the Post—and the Post would not buy any more stories. They always found something wrong with them too vague to remedy. When Rog tried them at other slick magazines the editors would say: “This is so obviously a Post story that I wonder you haven’t given it to them.” Rog told me it was just a symptom of what was happening to the magazine market and the reason he was urging all of his clients who could do so to shift to novels. He wanted me to take up the China novel again.

I still held back. I gave up on the Post and tried stories for the men’s magazines and even science fiction again. There was more desperation than pleasure in the work.

By July nine months had passed and I had made only one small sale. I realized I might just as well have been working on the novel all that while. With a sudden and angry resolution, I burnt my bridges. I went back to the novel with a vow as solemn as marriage that I would write it through to the end. I did not care whether I had a book contract or how many years it took.

At once the work went well and smoothly. My thirst for China reading came back redoubled. I rewrote Part I several times and sent it to Rog just before Christmas. I had built up a kind of momentum and 1 went right on with Part II while I was waiting to hear from Rog. Very soon I began to get the signal that the little man wanted to start over again, but with Part II. A feeling grew in me that the novel properly started with Part II. Late in January, with a curious kind of relief, I heard from Rog that Part I and my synopsis had again been rejected. I wrote Rog that I was scrapping Part I and that I was going to take the novel through a complete draft before I again showed anything to anyone. The next day I started afresh on Part II with the sense that I was at last really beginning a novel.

Thus began for me still another phase. My life began to contract wholly into my work. I became increasingly reluctant to go out evenings. I wanted the time for reading. But I could read nothing that did not in some way, not always known to me, relate to my work. When I tried to read simply for pleasure, I could not. Several times I hurled a book across the room and was astonished at myself afterward. I gave up reading newspapers on the plea to myself that I would keep up with the world by reading Time magazine every week. Then every Wednesday, when Time came blundering in like a Person from Porlock, I grew to hate the sight of it. Once I could not have imagined myself not reading the Scientific American avidly on its day of arrival, but now I was letting months of it pile up unread. Yet all the while I was reading voraciously, with the feeling that the demands of society would not let me read nearly as much as I needed.

My choice of reading was very whimsical. Sometimes I would read just the beginnings of novels and sometimes just the endings. For one stretch I read China novels and for another stretch I read dozens of military novels. I read a lot in the social sciences. All the while I read all the nonfiction China books I could find. When I did not know what I wanted to read next, I learned to go along the shelves of my library and leaf into books at random until one would engage my interest. When it did, I could almost feel the gears dick into place. The cutoff would be equally abrupt. One night Middlemarch clicked into place for me and an hour later clicked off. I don’t know what I wanted of it.

That was how it went for me. I wrote seven days a week and read every evening that I could. I became almost completely secluded. I would not answer letters. I let them pile up for months and then, resentfully, I would take a day off and answer them all at once. June neared and I wrote to my friends at Milford that I could not come that year. I was afraid that if I broke my stride even for a few days I would not be able to pick it up again. As I neared the end of the first draft in July a kind of superstitious terror grew in me, a haunting fear that some malignity of fate would stop me short. But nothing did, and I completed the first draft. I knew I had the novel nailed down.

Without loss of a day I began a second draft. In September I sent eight chapters and a synopsis up to Rog. I went right on working. In November Rog phoned me that Harper and Brothers were going to give me a contract for it. The news thrilled me and brought a tremendous exultation. I could not work any more that day. Nothing since has quite touched again the glory of that afternoon. After that, if possible, I worked with even more drive. The first half of the advance reached me just before Christmas. For my wife and me that was the happiest Christmas since our marriage six years before. On Christmas Day I wrote three thousand words.

In February I finished the second draft and went up to New York to confer with my editor, Marion S. Wyeth, Jr., on revisions. Rog joined us and we talked through a long afternoon in a rapport very like that of the workshop at Milford. I came home and worked on revisions at the same pace. I kept in close touch with Rog and with Buz Wyeth and our working rapport intensified. I no longer had the sense of being alone at my desk. It was a genuine group-mind that worked out the final form of Sand Pebbles. Although I wrote all the words, I know I could not possibly have taken the novel to finished form in isolation.

A few days before June I finished the work. Milford for my wife and me that year was almost all carnival.

The story of my development as a writer properly ends here. For almost a year now, I have not written anything of large scope. But I will recount briefly what has happened during the past year, because it is part of the larger story of my life in Chapel Hill.

Through July and August I worked up a quite detailed plot outline for another novel. In August the good news began, first the book club sale and then magazine serialization. In September I went to New York for the Times interview that was to break the story of the Harper Prize. While I was in New York the movie sale went through. And Rog went to the hospital with a heart attack and pulmonary complications.

I had brought the plot outline of the new novel with me to New York. Rog and Buz and I talked it over. From his hospital bed Rog negotiated a contract for it without a word of it yet written. I promised Rog that I would go right to work writing it. I said that when I came up in January for the publication of Sand Pebbles I would bring him one chapter of the new novel as a token.

I did not write a word of it. My correspondence had increased very greatly and I seemed to spend much of each day answering letters. Rog came out of the hospital but my health faltered and I went in for several weeks. I had still not fully recovered when I had to go back to New York in January. How I survived those three weeks in New York still amazes me. I promised Rog that I would bring him three chapters when I came up in February. Then I escaped home to Chapel Hill as if to a sanctuary.

It was no longer a sanctuary. I had a mountain of accumulated correspondence. I had to write speeches for delivery in Washington and New York. When I reached New York again in mid-February I did not even have one chapter of the new novel. Through all that stay, Rog chided me gently about my delay in getting back to my own proper work. He warned me at length of the difficulty of writing a second novel when the first has scored heavily. On my last night in New York we and our wives went out to dinner together and all evening he kept on that theme. When we said goodbye I slapped him on the shoulder and told him: “Rog, for sure now, I’m going home and go to work. We’re going to do it again.”

In Chapel Hill two days later I learned of his sudden death.

That brings my story up to date. Since last June I have not developed at all as a writer, although I have gained some competence at being a public figure of sorts. There is something frighteningly seductive about it. In another month I will have been idle for a full year and I hardly know where the time has gone. So for my own salvation as a writer I am going once again to burn my ships on the coast of Mexico.

I have set June 1st as an absolute cut-off date for all engagements which will work to delay or distract me from going to work full time on the new novel.

Let me in conclusion summarize what up to this point I think I have learned about professional writing. What I will say is not necessarily valid for anyone other than myself. And I speak from out the dust of continuing battle, so that I may interpret my experience somewhat differently ten years from now. But here is how it seems to me today.

Learning creative writing is a process of training the unconscious. We all have in us a living something independent of that which thinks it says “I” for the whole man. It is not enough to know it intellectually; one must also learn it through lived experience, which is a quite different way of knowing. What I did was to grant it a separate “I,” to personify it as “the little man.” I reached out my hand to him, and we clasped hands, to give help and to receive help.

At first the little man can only learn by doing, by blind trial and corrected error. It may take him years to learn on his level what the conscious mind can learn in a month of hard study. But the creative quality of what is written cannot improve any faster than the little man can learn. For that little man is the powerhouse of all creative writing.

He it is who explores the caverns measureless to man and therein listens to ancestral voices. He is the sole author, the scenarist and all of the actors in our private dreams. His original media are visual imagery and feeling tones and only a few spoken words. Until a few years ago, my little man was illiterate. Sometimes printed matter would appear in my dreams and when I tried to focus down and read it he would snatch it away. When I gained enough power over him to hold it in place, the presumed letters would turn out to be blurs and squiggles. There was great tension in the dream at such moments. But the time came when the letters were genuine and did not dissolve.

My theory of the moment is that the little man must learn how to change himself from a private to a public dreamer. He must learn how to transmute his original media into words in such a way that the story will induce in readers something resembling the unconscious, nonverbal complex of imagery and feeling tones he began with. The professionally written story may be a kind of collective and public dream.

From the start, my little man tried hard. I found my unsaleable first stories so deeply satisfying that it was very painful to cut and revise. I wanted just to reread them and glow with pleasure. In that phase the dreams were fully verbalized but still private. To make them collective and public demanded a subtle but equally as radical a change in verbal structuring as mirror drawing demands in hand-eye coordination. Now I take professional pride and find considerable pleasure in rewriting. I have little pleasure in reading the published work.

For me I think the preliminary movement was best and soonest made in painful isolation. Perhaps there had to be pain, to make the little man start learning. Along the way that I was going solicitous critical help too early might have been a hindrance; at least I felt it so. So would have been premature publication in any subsidized or coterie outlet. Both would have seemed to me a kind of substitute gratification, whereas the gratification I sought lay in breaking through to Everyman in the dust and heat of the common marketplace.

For me the breakthrough came in two critical junctures. I think with Casey Agonistes the little man first grasped the principle of public dreaming and thereafter set himself to learn and apply it more fully. I believe, however, that he still thought he was the only little man in the universe and that he was still working for the familiar single spectator, who had suddenly grown outrageously demanding. Not until well over a year later did he learn from Hemingway that the theater was really public and all the seats were filled with other little men just like himself.

That, I think, was the source of the strange excitement with which he and I read Hemingway that time. My little man was learning that he was not alone. The clean, well lighted story has in it a quality of deep calling to deep which will not yield to critical analysis. It can never be improved upon or demanded of the little man by the intellect. It is the treasure that he must alone and voluntarily bring up from the deep waters. When he can bring it safely to shore he breaks free of the solitary confinement into which the evolving human condition has plunged all the little men. Momentarily he can permit the other little men to feel that they are not alone either.

They say Leonardo was ambidextrous from infancy and could write in mirror- reversal without ever having had to practice it. Maybe he painted Mona Lisa in some looking-glass way that makes her a universal public dream-image. Possibly Leonardo remained a whole man from birth. I know that I did not. But more and more I find the little man and myself tending to coexist in the same “I.” Perhaps the measure of artistic maturity is the degree of that coexistence and the calm joy it brings is the true reward of writing.