THE EDITORS of Better Homes and Gardens magazine unwittingly played right into the hands of G. T. Fleming-Roberts of Brown County, Indiana, when they printed a piece of advice on picking lilies a few months ago.

Pull off the stamens, the magazine suggested, and the lilies won’t stain themselves—surely as innocent a tip on gardening as ever got tacked up on a toolshed wall. But Roberts crowded the information onto the bottom of a sheet of paper he keeps filled with random ideas on how to commit or detect murder.

“Expert gardeners probably know about pulling off the stamens of lilies,” he explains, “but would an amateur?

Probably not.” He lowers his voice to a whisper. “It’s Just one of those details.” he says, “that a murderer overlooks—a murderer, say, posing as a skilled gardener.”

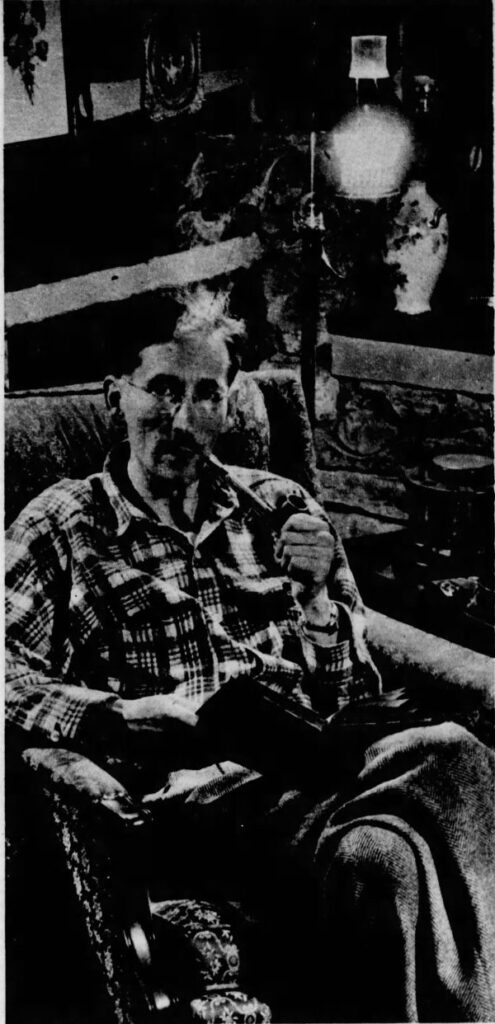

Twisting the everyday facts of life into patterns of mystery and terror is trade with the tall, slim, 37-year-old writer, whose business is currently so good that the mere sight of his hyphenated name on a pulp magazine cover is enough to make a reader start digging for 15 cents.

SINCE HE began writing 15 years ago Roberts has turned out some 450 detective and mystery stories. Most of them have been published under his name, but whenever two or more of his tales turned up in the same publication, they have appeared under any other name the editor found handy. He is the author of a novel, “The Lisping Man,” a story so popular that it was published four times —in a magazine, as a book, as a reprint “Mystery of the Month,” and in England as a novel again. Each time it appeared under the name of Frank Rawlings, because after writing it Roberts thought poorly of it.

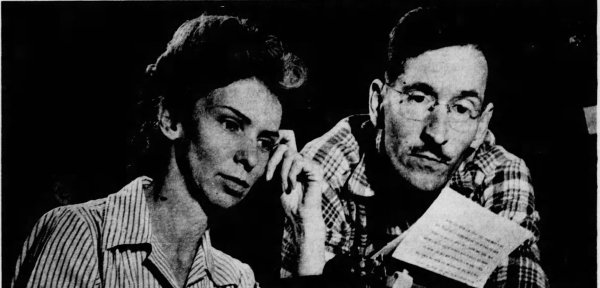

At the “Witch House,” a home near Nashville where Roberts moved about two years ago with his wife, his 5-year old son and his mother, they no longer use the fireplace tools for anything but stirring up the fire. “Old stuff to murder somebody with a poker,” explain Mrs. Roberts, a versatile woman who was city treasurer of East Lansing, Mich., for two terms before she married the lanky Hoosier and became his chief literary critic and adviser. Such remarks remind Roberts that inventing his kind of story is no longer a simple matter of going “Boo” at the read! “from the body to the bitter end.”

For example, Carolyn Fenton, the shaky heroine of a Roberts mystery novelette published this winter, suffered the author, through the villain of the piece, to drive her to the point of hi sanity with nothing more terrifying than the sight and sound of a bouncing tennis ball. In another Roberts chiller the menace was only an ordinary strongbox which happened to remain locked.

“The menace nowadays has to be something common and familiar,” Roberts maintains. “Adults are reading the magazines—kids dropped them in favor of comic books—and you cant scare grownup mystery story readers with a slinking figure in a black cape or a nasty old clutching hand.”

READERS of Roberts’ detective fiction are also a sophisticated lot, bored experts who drowse off if the shapely heroine is done in with a dagger contritely shot by a party who then disappears. Here again Roberts delights in making malign use of common things in order to give readers a murder they can get their teeth into.

One successful device — called a “Rube Goldberg” in the trade—was worked out in the Roberts living room with Mrs. Roberts’ tape measure, a pistol and the family’s secretary-bookcase. Roberts and his wife spent a whole evening getting the tape measure to fire the revolver when the gun was removed from a bookshelf, and then to fall out of sight so completely that the coroner in that story could return no verdict but the false one of suicide. Roberts’ fiction detective had to find the tape measure in a cold-air duct behind the secretary but not, of course, until the climactic moment.

For an author whose fictional people move in a world bristling with every danger from arsenic to planted gun Roberts’ private life is reassuringly tame. Even the “Witch House,” a rustic place of square-hewn logs, massive fireplaces and hilly views in all directions is sinister in name only. Perched on a commanding rise between the Beanblossom Lookout and Nashville on State Road 135, it tempted Roberts to name it the “Witch House” because of s resemblance to the cottage made of candy and gingerbread in the children’s tale, “Hansel and Gretel.”

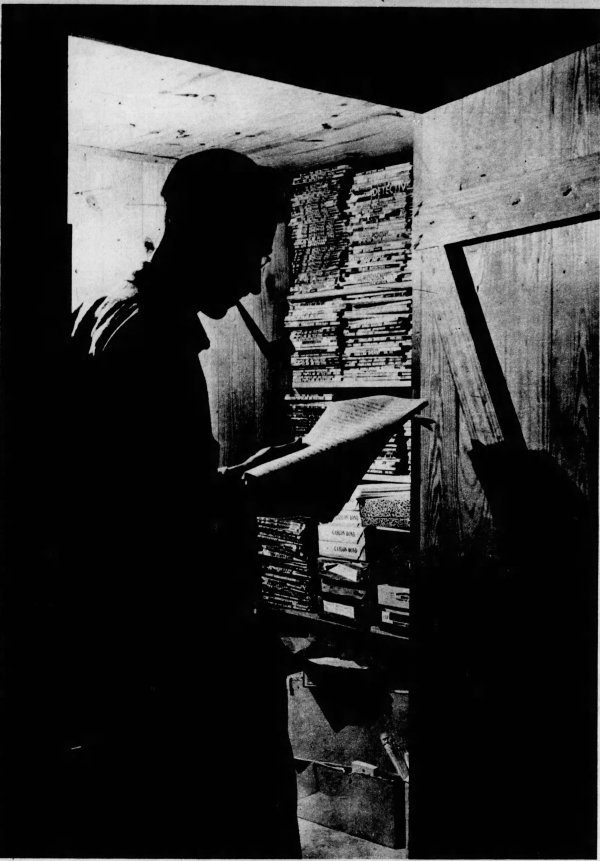

SHOWING friends around, Roberts fads them to the spare, book-crammed lean-to on the back of the garage where he does his writing, and lets them inspect the library of technical books on medicine, crime and police science on which he relies for information. Recently he took down one of his rare volumes. “Murderer’s Manual,” to show a visitor such interesting facts as that most suicides cut their throats from left to right and a dead body cools in eight to 24 ours, depending on atmospheric and other conditions. When he opened the grisly text a lace valentine fell out of it.

The only lethal weapons in the Roberts household are an air pistol, which is jammed and won’t shoot, and a .38 caliber revolver for which there are no bullets. The revolver belonged to Roberts’ father, the late George H. Roberts, professor of veterinary surgery at Purdue University, who killed mad dogs with it while he was practicing as a veterinary in Indianapolis. Roberts never used the gun except as a paperweight or to work out Rube Goldbergs with it.

Born in Indianapolis in 1910, he grew up with no literary ambitions except to please his English teachers, which came easily for him, and was graduated from Purdue in the depression 15 years ago with a good BS. degree and a broken Oliver typewriter, on which the carriage wouldn’t return. While awaiting action on an application for a teacher’s license, he propped a book under one side of the Oliver, so that gravity made it work, and wrote four short detective stories.

Nothing came of the application, but magazine editors promptly rejected the stories. Roberts forgot about becoming a teacher while he found an agent to tell him what was wrong with them; the agent told him, and, consequently, Roberts has never worked at a wage or salary job—a fact one college postgraduate found particularly frustrating when she went to Roberts for material on her thesis, “Newspaper Work As a Background for Writing.”

REWRITING his fourth story under the agent’s advice, Roberts made his first sale 11 months after graduation from Purdue. Ten Detective Aces magazine paid him only $25 for it, but that was enough to make him a writer for life. It threatened to be a short life, however. Roberts began to emulate the late William Wallace Cook, a phenomenally successful pulp writer who wrote so much fiction that he became known as “the man who deforested Canada.” For 12 years Roberts wrote from 8 to 11:30 each morning, 12:30 to 4 each afternoon and 6 to 10 o’clock each night, Sundays included—11 hours a day.

As rejections diminished—for seven years he has sold everything he has written—he began to enjoy the experience of filling up entire magazines under half a dozen names, and for several months, he recalls, he even designed the cover and edited, from his desk in Indianapolis, a magazine published in New York. His close alliance with that magazine resulted in a disappointment peculiar to writing.

The editor, a woman and a New Yorker, instructed Roberts to write into his next novel a chapter set in Chinatown. He protested that he had never been to New York’s or any other city’s Chinatown, but she replied that she would research the area for him. Working with her material, Roberts wrote a chapter deeply flavored with Oriental guile and studded with laundry signs and cellar restaurants. When the story appeared, he saw with a shock that the editor had cut only one thing out—the chapter set in Chinatown.

SlNCE then Roberts’ relations with editors and his own typewriter—one that works—are a little easier. Now one of the name writers in his field, his by-line is sufficient for a sale without the added attraction of chapters with specific settings. The hyphenated name happens to be accidental. Plain Tommy Roberts to his family and friends, he packs the full name of G. T. Fleming-Roberts, formidable enough without the hyphen, which surprised Roberts himself when his first story appeared in print.

“I was too shy to put my name on manuscripts in those days,” he says, “but I did write my agent I didn’t bother to raise the pen when I wrote the Fleming and the Roberts. He thought the scratch was a hyphen.”

Roberts now works seven days a week, but no longer nights, and produces 24 stories a year. Usually of novelette length, about 15,000 words, each grows from some fact like the cause of lily stains and matures thoroughly in its author’s head before he commits it to paper. While he is thinking out a story Roberts weighs the full possibilities of human depravity and a single story will contain several juicy incidents each as original as it is evil.

The villain of the tennis ball story, for instance, murders one wife by chocking her automobile at the edge of a cliff with blocks of ice. The ice melts; the car and wife go over. He causes the disappearance of a second wife merely by hiding her body in a grave already prepared for somebody else’s funeral. He goes after No. 3 with the Tennis balls because he knows they recall to her tormented mind a childhood of pain and tragedy.

Shortly after he finished that story Roberts left his house one morning and walked across the back yard to the garage for another day of work on a new one. In a few minutes he was back in the kitchen explaining to his wife that a blacksnake had crawled into his study and was asleep beside the stove. She obligingly went to the garage and killed it for him. Roberts isn’t particularly afraid of snakes, however. “I just can’t stand to kill anything,” he says. “I never could.”

This article by Robert E. Johnson with photos by Tim Timmerman originally appeared in the Indianapolis Star, Dec 21, 1947.