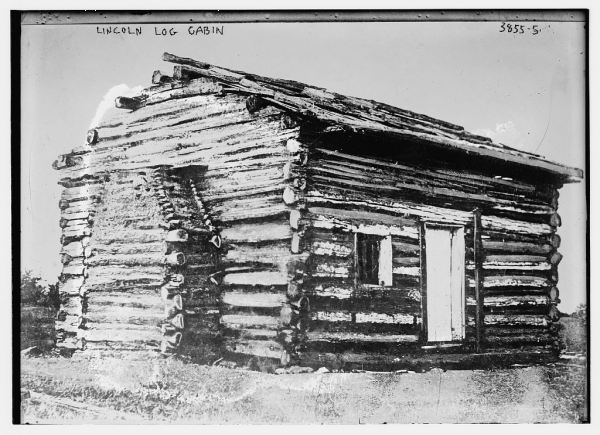

When you think of a homestead, you probably think of something like this, the log cabin where Abraham Lincoln was born; but Cherry Wilson and her husband Bob homesteaded in the 1920s, driven by Bob’s tuberculosis into a place where they needed fresh air and quiet. This is her account of their experience, published in the Spokane Spokesman-Review in 1921.

To me life on a homestead had always seemed a romantic sort of existence, my ideas being formed for the most part through fiction; so when fate kindly set me down on one, to sink or swim, survive or perish, I was utterly at a loss how to gather up the loose threads of this new life. Since I had never lived more than a stone’s throw from markets and neighbors, a home in the wilderness presented problems the farmer’s wife would have smiled at. It came about this way:

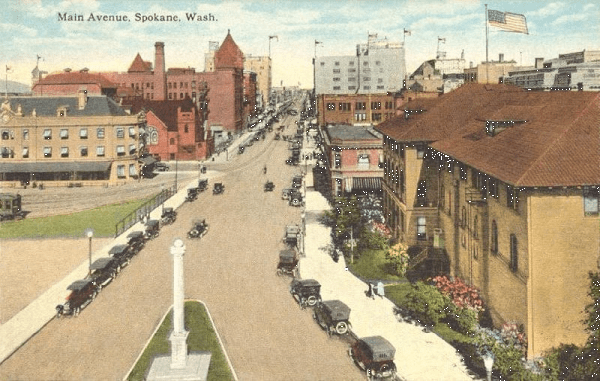

We were living in the city of Spokane, Wash., where I was desultorily writing feature articles and my husband employed in an electrical garage, when the mandate came to move. The return of an old, annoying cough, overpowering fatigue at the least exertion, loss of weight and sleep, had occasioned another consultation with our physician, bringing the verdict that my husband’s case of tuberculosis, for a year inactive, was again playing deadly havoc.

“You must get out of here at once,” the doctor gravely ordered. “Go somewhere in the mountains, where every breath you draw into your lungs will be one of pure untainted air. The climate doesn’t matter as much as the fact that you have quiet and live in the open.” The doctor must have been puzzled at the cheerful—yes, happy—manner in which Bob heard the advice; But I had long divined how he disliked city life and all pertaining thereto, and how he longed to return to the mountains, where he had grown to manhood and where his family still lived.

Our guardian angel must have been on duty for once, as that very afternoon came a letter from an acquaintance of Bob stating that he was tired of the isolation of his homestead and would like to sell the relinquishment. So clearly did this seem an interposition on the part of Providence that we immediately decided to buy; discussing ways and means while packing up.

“It’s a pretty place—about 87 acres.” Bob informed me, he having visited the spot once. “Covered entirely with timber and rough, not level ground enough on it for a tennis court. Though it’s only two miles from Republic, every foot of it is straight uphill. It’s impossible for cars to climb there, and, as I remember it, there is a very precarious wagon road built by mills and a rough foot trail that cuts off half a mile. Not a sign of human habitation nearer than town—we will own our mountain top in all its solitary grandeur.”

“But the house,” I protested, “remember this is December of one of the coldest winters ever experienced here. We simply can’t go up there without some sort of a respectable house.”z

“Ohh, there’s the cabin Mills put up.” replied the masculine side of the house easily. “It will do fine until we can build a new one—think how lucky we are to get a homestead so near town. There isn’t another within twenty miles.”

“But the house—how large is it?”

My opinion of log cabins was firmly fixed by the low, squat structures encountered in my journeyings, in which it would seem impossible to stand erect unless in the middle of them.

“I don’t remember, but it’s airtight—about 12 by 14, I think and maybe 6 feet high.”

Do you wonder that my heart sank at the prospects of being cooped up for an indefinite period in a cabin of such meager dimensions “amid all the solitary grandeur of my mountain top”? But a glance at the pale, drawn face alight with enthusiasm opposite me gave my conscience a twinge. After all, I consoled myself, two miles is a very short distance—but I was reckoning by city miles.

Next morning found us hastening towards our new home as fast as the erratic little local would permit; And I must not forget to mention the other important member of our family travelling in the baggage car—Pete, the dark complexioned little alley kitten that we found one bitter cold morning, stealing our breakfast from our garbage can and straightway adopted. What Pete thought of the proposed move we never thought to inquire. But when the train drew in at Marcus, where it laid over 30 minutes, we visited the baggage car and were welcomed with plaintive mews.

About 1:00 PM the train crossed the Canadian border, where it made a great loop, reentering the United States at the town of Danville. British customs officials had boarded the coaches at Laurier, searching luggage with an impressive air of great authority.

The scenery was interesting, with its series after series of fan shaped mountain ridges interspersed with fertile valleys. Truly nature had been prolific in this, her playground. There were heavily timbered mountains, great iron streaked columns and soaring pinnacles. The frequent mountain streams were chained by winter—even the great Columbia was frozen almost its entire width. Curlew Lake, near our destination, was an unbroken sheet of ice, as was the San Poil. It was dark when we alighted at the little depot of Republic, and almost unbearably cold. One might truthfully say that our new venture did not meet with a warm reception.

I shall never forget that breathtaking climb of the dark mountain flanking our proposed homestead. For the first time in my life I understood what two miles may mean, given the right locality and season. Fortunately the snow was not deep, but being unbroken called for all my energy to make the ascent. The temperature hovered about 28 degrees below zero, our sharp breathing pained the lungs like stab thrusts. Before leaving, Bob had wrapped my feet and legs in multitudinous strips of gunnysack lest I suffer from cold.

But all things end at last, so eventually we reached the summit and in a little mesa before us, at the very margin of the black forest stretching away as far as I could follow in a scalloping of feathery tree tops, was a little cabin. At that distance it was not so unprepossessing as I had pictured—or perhaps it was the ideal setting that lent it charm, being a sturdy building of unpeeled logs, boasting one window on each of two sides, and having an unfinished appearance. Once inside the prospects were dismaying. White gaps showed where the chinking had fallen out. One could have thrown a cat through many of the apertures—a much larger cat than Pete. The door, made of green lumber, had shrunken till it resembled a picket fence. A rusty bedstead stood in one corner, a tiny, rusty cookstove graced another, while three crippled chairs dared one to repose.

I sank on the least deformed of these, while the ever cheerful Bob tried to woo a flame out of a wet magazine and wetter wood. I wondered absently why he troubled; one might just as well build a fire under the trees that I was viewing through the open space between the logs. But he was so thoroughly in love with the prospects, so like a boy on a new adventure, that when he asked how I liked it all, I managed to evade the question and say that the cabin was better “than I had expected”—at least one could stand up in it. Nevertheless, my heart was in a state of rebellion. Surely it could not be helpful for anyone to live in such a place, especially a tubercular person. Could it ever be made livable?

The next morning we bought the relinquishment and filed on the homestead. The die once cast, I felt better. A few hours later we were on our way homeward. A sled, drawn by four horses, was laden with our trunks and most needful furniture. In order to keep warm I walked ahead, with Pete snuggled close under my coat. It seemed an eternity after reaching the cabin before the sled arrived, the horses coated with sweat that hung in ice crystals on their thick hair. I was told the load had tipped over four times, and the state of my belongings surely proved it.

What use to relieve the chaotic jumble that ensued. Both of us went swiftly to work that we might not freeze, for it was even colder than the day before. Bob had filled the stove with dry limbs, and it glowed a cherry red, yet one could stand over it and feel no warmth. Our breath hung in frost clouds before us all that day we kept our heavy wraps on and with all my heart I pitied Pete curled up forlornly on a box near the fire taking not the slightest interest in our surroundings. So while stuffing sacks, rags, bits of carpet, everything and anything at hand into the unsightly cracks through which poured great quantities of the fresh air the doctor had ordered, I comforted myself by the thought that I was now a homesteader, subject to all their privations—one of the blest.

That’s part 1. Be back for part 2 next week.