Part 3 of a personal account of homesteading in the 1920s by western author Cherry Wilson.

But to go back to those first glorious days of Spring, after the eventful Winter; when the very air made one’s head light. The call of the outdoor was so strong that while snow still lay in canyon pockets and brushy patches, every hour of daylight found us beautifying our homestead or making it more accessible.

During the winter we learned a lesson that came near being tragic—the doctor had been needed in a hurry and it had taken him several hours to make the short trip. With this in mind we turned our attention to building a road down the mountain-side. It was a puzzle to task the most ingenious, to pick out a gradual grade down the craggy, cut-up slope. Often we found one only to be confronted at last by a sheer drop-off into oblivion, but nothing daunted, started over again. When the trail was once blazed, the small brush cleared away, the mules did good service again by dragging aside logs and pulling the road plow. Evenings, we burned brush about the cabin, having as many fires going as we could both look after. The land began to wear a llved-in expression.

Clearing land was grim work, but satisfying, and we were playing the game of being pioneers, quite as if we had lived a generation before. The homestead law required that we put in cultivation the first year one-sixteenth of the land taken up. With a hook the seemingly hopeless snarl of vine maples, buck-brush and wild rose was cut away and piled in great heaps at one side of the clearing to be burned. The largest trees were cut into wood; some of the stumps blasted out. others left in the ground to rot. But the cleared area was such a tangle of roots that the plow had to be heavily weighted. The soil thus torn up was loose and sod-bound, added to this there was a shortage of rainfall that season, so our first crop—wheat—was not up to expectations. This summer we will have better success for the small stuff will have rotted and the soil lend itself better to pulverization.

With the crop once in I launched upon an extensive propaganda for a new house, so one bright day we selected a pretty little mesa out from the timber, where our new home would always stand in the sunshine. A few large pines for sentinels, a ridge at the north to shield it from winter winds, and at the south it would face a beautiful willow grove, then in bud.

In our anxiety to make a beginning we picked out a straight, slim tamarack for the foundation log, and with me at one end of the saw and Bob at the other brought it crashing to the earth. Our new home was under construction! A friendly breeze must have borne the news far and wide, for neighbors flocked to our assistance. I prepared meals in the little cabin while the men folks cut down trees and teams skidded them to the chosen spot. Once a quantity of logs were on the ground the house went up as if by magic—the walls being raised in one day. While one man saddled the logs to fit others hoisted up new ones. A huge lumberjack with a complexion any girl might have envied, mounted each log as it was rolled in place, hewing the inside with a broadaxe as smoothly as though planed. What conflicting advice we were given, much of it ridiculous, but my plans had been made in the leisure of long winter evenings and were adhered to. Mountaineers contended that peeling the logs would make them last longer, but I wanted the pretty bark on, if a new house had to be built annually. Old-timers insisted on boughten doors with knobs to “make it look just as good as a frame house”. It seemed impossible to make them understand what I wanted was the loggiest log cabin imaginable. After it was all done the verdict was unanimous that it was the prettiest log cabin in the country.

I rather overdid it though, in the matter of windows, remembering the dearth of them suffered in the old cabin—windows to right of us, windows to left of us, windows in front of us glinted and glimmered. If this was a fault at any rate it was a good one.

With a borrowed froe, Bob split shakes from a straight-framed tamarack, thereby making a better roof for all purposes than the most expensive shingled one.

From the day our cabin was begun until its completion was but a week. Since the inside walls were hewn, chinking had to be carefully done, this consuming the most time. It cost us only $30 in all, the biggest item of expense being nails for fastening shakes and window casements—none, of course, were used in the walls. Flooring and windows we bought second-hand, picked up almost for a song. The doors were made of planed boards, adorned with quaint latches of Bob’s designing. No millionaire could have been prouder of his home than we, of course.

I undertook the task of painting— my first essay in this field. Windows came first, and so zealous was I that most of the glass received a liberal coat, a fact that caused me much grief, turpentine, kerosene, soap and what not to eradicate. In the same restful shade of brown was painted the built-in wardrobe, cupboard and book shelves, floors and all the woodwork.

The most disagreeable task came last—one that hurt me to the soul— the very necessary one of daubing. All day we mixed clay and water in a large tub (mud pies on a grand scale), then Bob threw millions of handfuls of this mixture on the new logs. For a long time I just stood and grieved as each gob splashed on the house. Then, making myself a wooden paddle, I followed him about smoothing the mud in the creases. It was a terrible sight to contemplate, when once we were done and looked upon the havoc we had wrought with aching arms. But in a day the excess mud dried, falling off, or was not discernible. The white strips between each log were distinctly ornamental. Bob still laughs at my previous declaration to scrub the house clean again.

The snowy blossoms of the wild service had transformed our homestead into a veritable fairyland, when we took possession of our new home. We had now two rooms separated by a log partition, and a large sleeping porch. Small, some may say, but palatial to us. The living room was 14 by 18, the kitchen 10 by 14. We have never felt cramped for space— it is all-sufficient. What two people need of more, unless they entertain extensively, is more than we can fathom.

Summer now burst upon us in all its glory, with the most prodigious wealth of wild flowers I had seen—lavender rock roses, scarlet fireweed, purple larkspur, blue bells, yellow bells, heavenly lupine, and, a little later, goldenrod in an endless galaxy of color. Tamaracks had put on their fresh new dresses, as had the cottonwoods. Dark green pine grass grew rank in the big yard I had raked and re-raked. The hills were one vast lawn, to which the bunch grass lent a lighter tint. One canyon we discovered to be literally carpeted with white violets.

Bob had bought each of us a saddle pony and outfit, so we rejoiced to ride away when work was done, over the ridges, striking off the faintly marked deer trails or jog our mounts over deadfalls laughing the while in sheer enjoyment of our new-found world. Very far away did the old days seem of crowded streets, matinees and gossipy teas.

Our forest home simply abounded with life. Deer, we saw often frequently grazing with the horses, or in groups—does with their pretty spotted fawns, occasionally guarded by a many-antlered buck. At all hours of the day could be heard the drumming of grouse, several coveys actually lost their native shyness and made friends with us. And song birds! The clamor that arose to heaven at the first peep of day led us to believe that every member of the feathered species in the state of Washington was nesting in the willows by the porch. Needless to say, we became early risers.

Nor did we longer have the feeling of being shut in. In half an hour we could scramble down the steep foot trail and reach town—it took an hour of hard climbing to return. The next few months found our homestead the scene of many pleasant gatherings. Most of the visitors arrived on horseback, the hardier ones on foot, or came as far as possible by car, then climb to the summit.

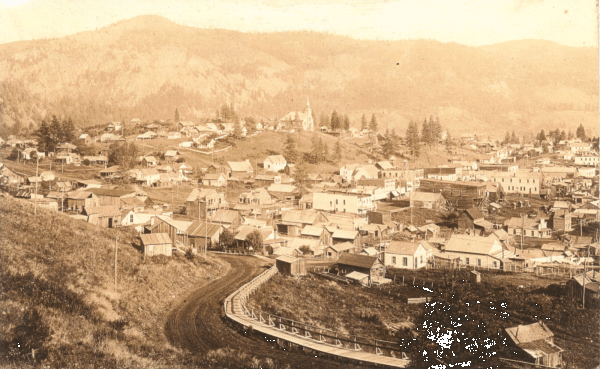

Perhaps it would not be amiss to put in a word about Republic, since the homesteader’s nearest town is always an important factor, and ours was a town with a personality. All through the ages up till 1896 this country was a wilderness, where only a few scattered Indians dwelt. But in the spring of that year a nomadic prospector discovered gold—then came the flood of civilization. In a frenzy of madness thousands poured over the mountain trails—the city of Republic being built almost overnight—a typical mining camp, with one long street of frame buildings housing at the height about 10,000 souls and every other door being a dance hall of saloon. All forms of gambling flourished, there was even a wildly speculating stock exchange. Every foot of ground for miles around was staked in claims; thousands of shafts were sunk. The mountain streams were panned for the precious metal. Millions of dollars worth of high grade ore were taken from the hills, fortunes were found at the grass roots. At length the excitement abated, the wild cats were abandoned and the best paying mines intensively developed. Three times has Republic suffered devastating fires and in the rebuilding lost much of her old picturesqueness, yet whole blocks of the original city still stand—forsaken and deserted—and to me, an endless treasure trove.

Our homestead, being on the same ledge with the richest finds, was the scene of frantic work. No less than ten deep shafts have been sunk here and the land is a honeycomb of prospect holes. Little rails still lie beside sagging shafts. Moss-covered tunnels drip with moisture, hastily put up boarding houses and blacksmith shops are undergoing rapid disintegration. I planted nasturtiums in ore buckets collected from old diggings, making them an attraction to the grounds.

The shaft of the Golden Lily mine is within a few feet of the kitchen door. At a depth of 200 feet water rushed in faster than it could be pumped out, so the miners abandoned it, leaving their tools in the shaft in their haste. This furnishes an endless supply of water for laundry purposes, we even plan on irrigating the garden with it next year, for the first dry year taught us many lessons.

After the early spring rains almost no moisture fell, this lack bringing on the greatest dread we had yet faced—forest fires!

Next week comes the fourth and final part with the couple’s almost fatal adventure.