Part 2 of a personal account of homesteading in the 1920s by western author Cherry Wilson.

Two days later, when order was established, we looked with pardonable pride upon our work. For out of that rude shack we had made a home. The bare logs were hung with bright pennants, cheery curtains of cretonne draped the windows without excluding any of the precious light. One-half of the floor space was covered with linoleum, designating my kitchen and laundry; the other half being carpeted and when one crossed the division line, he was in my bedroom, studio and parlor. Bob had built a small rustic table to fit the space between the foot of the bed and the window to hold my typewriter and built shelves above it for my most used books. Almost in the middle of the room had been set up a large heater, wherein a fire of fir crackled merrily.

The feeling of freeness, of complete aloneness was such a distinct novelty that we spent the next few days enjoying it. Not a sound but of our own making disturbed the stillness. The spell seemed also to have fallen over the pine squirrels and snowbirds that we fed each day. What wonderful long evenings we passed, taking turns reading aloud books that had been laid aside for lack of opportunity. Of these, I think, Ossian’s poems afforded the most spirited discussion. What pleasure it was to listen to the song, ever mournful, of the wind in the pine forests. But there is a serpent in every Eden, so before many idle days I found myself wondering how we would support ourselves since we toiled not neither did we spin. Bob, however, reassured me, “You forget, my dear, that we own a million and a half feet of first class timber, which I propose to convert into honest- to-goodness dollars.”

So the next morning, armed with an old crosscut saw and his usual enthusiasm, he set to work. Near the cabin was a giant, wind-blown tamarack. This was the scene of his first attack. All day I heard the sounds of his industry and at nightfall he came in, white and exhausted, but triumphant. “Come and view the slaughter,” he begged with pride. And there, very precisely piled, were about two ricks of dry, seasoned wood. My hopes rose, only to fall at the speed with which those two hungry stoves consumed the fuel. In a few days it was evident, even to a rank beginner like myself, that the wood business was a poor food producer. We had a few cords on hand, but the difficulty of getting it to market was insurmountable. It would have been a hard task even in summer, but in the present condition of the road was now impossible. There was insufficient snow for sledding, and a wagon was out of the question. Then it was that my little checks for writing stood us in good stead, but soon we stumbled upon a new and totally unsuspected source of income. For many nights our dreams had been shattered by the weird, blood-curdling bowls of coyotes and as their furs were valuable, we planned to turn a few of our tormentors into cash.

We found ordinary methods of trapping of no avail, since the coyote is the most cunning and cowardly of animals. Snow sets placed in their runway— which were all about the ranch—brought us some success. During a period when they had been unusually wary I recalled one ingenious trapper’s scheme of using a live cat for bait. So under the cloak of necessity, I planned to make Pete “vamp” the creatures to their destruction. All that day I tried to quiet my conscience by giving her extra saucers of milk, but when night came my heart almost failed me. Resolutely putting her in a little box with a piece of blanket to rest on and a generous supply of meat, I set out, cat, box et al., for one of the coyote boulevards. Here I nailed the box fast to a tree, just out of reach of covetous claws. After carefully setting several traps beneath, I swept snow over them with an evergreen bough so there would be no scent. Then with many farewell apologies to the kitten, I returned home. The psychology of this plot must be that the coyote, lured by the cat’s howling, will jump for it, only to fall in one or the other of the waiting traps.

Sleep forsook my pillow that night for wild imaginings of Pete’s plight. What if a coyote succeeded in reaching her? I felt like a betrayer. As soon as it was light I ran out to see. I must have made her too comfortable to create any disturbance, however, for I found my Lorelei sweetly sleeping and no new tracks in the vicinity.

We got several fine pelts during the winter, but I’ll have to confess that we shot most of the animals. In our case the gun was mightier than the trap. In addition to coyotes, there were many other tracks in the snow, some of which we recognized—- lynx, mink, ermine and fisher. These furs helped supply the larder in the months that followed.

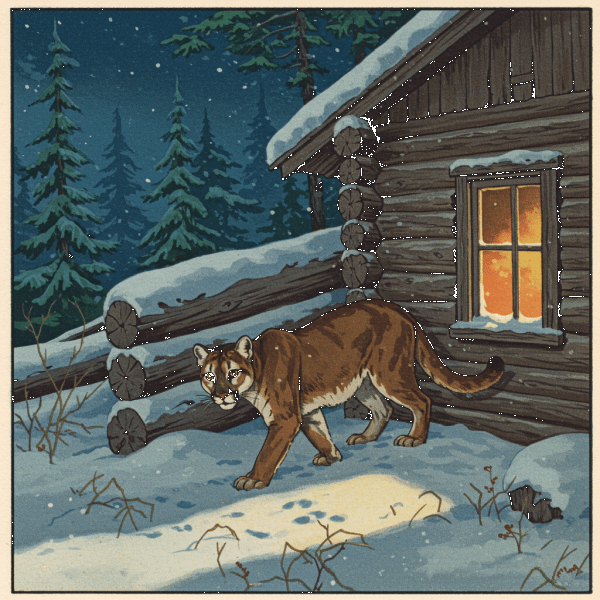

One night, while quietly reading, we were startled by a slight crunching in the snow outside, then a sound as of a heavy body brushing against the cabin. Bob went out to reconnoiter, but in the darkness could discern nothing. Next morning near his tracks were those of an enormous cougar that had evidently been driven by hunger to thus boldly seek food. I was nervous for weeks at the thought of how near sudden, horrible death I had been. A few days later a mountaineer killed one of these great cats, measuring seven feet.

To novices like ourselves trapping was a precarious means of existence; then, too, we had to look forward to the summer months when this would be denied us and devise something else.

“Are you discouraged?” Bob asked, one night when he had summed up our assets. But I was not. I seldom get discouraged when expected to, and we had life, health was returning, and we had each other.

It was about this time that a neighbor dropped in. When I say “nelghbor,” understand that the nearest one was farther away in the opposite direction than was town. The three who lived closest were at the foot of another ridge west of our claim, and while inaccessible to us, were not cut off from the outside world as we were, since they were near the highway in the valley.

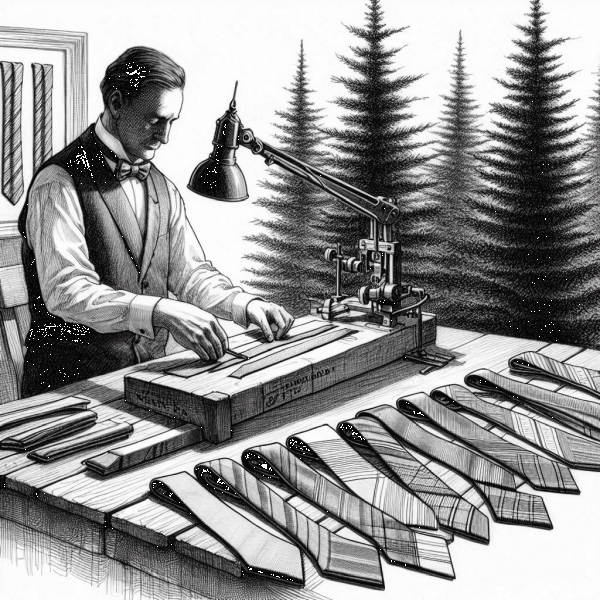

“Why don’t you make ties?” was his first inquiry.

“I don’t know anything about it,” Bob answered.

“Anyone can do it—I’ll stay a few days until you learn the ropes.” So we became, in the lumberjack’s vernacular, tiehackers.

Does anything seem more wholly forsaken than a blackened, battered railroad tie. Endless are the stories we view about a cast-off glove, an old shoe speaks eloquently of miles of travel, a warped, weather beaten house has limitless possibilities for the errant fancy—but a tie! Yet it does have romance—real, virile, primitive. Back of it is the tang of piney forests, the whine of crashing trees, the ring of ax and saw, the flash of blades, the clean, fascinating labour of tie-making.

Our first specimens might have caused a veteran of the woods convulsions of mirth, but we viewed them with pride, sort of a “poor thing but mine own” attitude. They were accepted and with experience we gained skill. I say “we”, for I liked to help fall the timber and strip the bark. The work in the open did us both good; we acquired endurance and appetites. Bob, whose stomach had demanded coaxing for so many years, could now eat anything. Often, coming in from the woods, I asked what he would like best for dinner. “I don’t care as long as you can get it quick,” grew to be the invariable reply.

After the ties were made and skidded in piles by the roadside the same problem faced us as in marketing the wood. It was summer after the new road had been built before hauling was done to any extent. Even then the grade was unbelievably steep and winding, necessitating both rough-lock and brake. In this work we were fortunate in having the use of horses without an outlay of cash as Bob’s father, living in Republic, had turned his stock on our land to range.

A small idea of the grade can be gathered when I state that the mules, two powerful animals weighing about 1600 lbs each, were barely able to drag back the empty wagon stripped to the wheels with only the tie-frame, and resting every few feet. For pure, unadulterated thrills nothing could be more productive than a ride down the mountain side on a high load of ties. I often went clutching the binding chains like grim death and screaming every time the teetering load struck a snag. Once we narrowly averted a serious accident. It was in the early spring and the ground being soft, we depended on this holding back the load, so set off with only the brake on. But at the steepest pitch the mules were unable to withstand the weight and there was nothing to do but outrun it. It was a wild ride, and only the fact that we were near the bottom saved us from injury. We never risked a repetition of that hairbreadth escape.

This was the work that enabled us to stay on our homestead until the day when the soil will support us. We cannot sell the saw timber until we receive the deed, so the task of clearing land will proceed slowly.

Part 3 next week.

PS: While researching this article, I found that there’s a memorial in Dubois, Wyoming honoring tiehackers.

https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/49838

Worth visiting if you’re in the vicinity. Share some photos if you went there.