Till Barry Traylor posted a photo in a Facebook group, I had no idea that this pulp existed. I had never seen an issue or read a story from it, but that didn’t make me any less curious about it. It was one of the many magazines that hitched their star to the rapidly rising movie industry in an attempt to grab an audience’s attention. Sometimes that trick worked, this time it didn’t. We know about the successes, but how much attention do we pay to the might-have-beens? This is the story behind this little-known pulp, as far as I’ve been able to find out.

It starts with Vincent Rosemon who was born in 1854 in East Setauket. He lived in Brooklyn and practiced as lawyer in NYC from the 1870s till nearly 1920. A successful lawyer, he represented insurance companies and was an authorized notary public for all states.

Vincent married Rebecca Dunn of New York City in 1874. Their first child, Vincent Rosemon Jr. died a day after he was born in 1882. A daughter, Ethel May Rosemon, was born on September 4, 1883. When Ethel was 7 years old, her mother Rebecca died. Ethel was an only child. Vincent married Mamie V Bowes in 1891, a few days after his daughter’s eighth birthday.

As a prominent lawyer, Vincent could afford to send his only child to college. Ethel attended Columbia University and graduated from Barnard College. At Barnard she was a member of the acting club, the Chi Omega Sorority and the Barnard Club. Still a teenager, she was a member of New York’s upper class society and her parties and social activities were reported in the local newspapers. After graduating, she taught in the Eastern New York public school system for a brief period.

By 1910 she was working as a journalist and had become a member of the New Jersey Women’s Press Club. She wrote a series of articles on the theatre and theatregoers that ran under her byline in the Newark Evening Star. In 1916, she joined the Orange Chronicle, East Orange, as society editor. Not content with one career, she also dabbled in the stage, acting in amateur productions and taking part in stock company productions and was active as a suffragist. A busy woman.

Call it serendipity, chance or luck; she was in the right place at the right time to work in movies. New Jersey, not Hollywood, was the hub of the American film industry in the 1900s and 1910s. Edison in his laboratories in West Orange had been perfecting motion picture technology – working in both film and sound. Powered by Edison’s patents, his studios produced many movies and attracted talent to New Jersey.

With the launch of the film industry, movie periodicals of all kinds sprung up like dandelions. There were newspapers and magazines for the trade (Variety added film news, studios published their own trade magazines), gossip rags, magazines that ran screenplays as stories and profiles of movie stars.

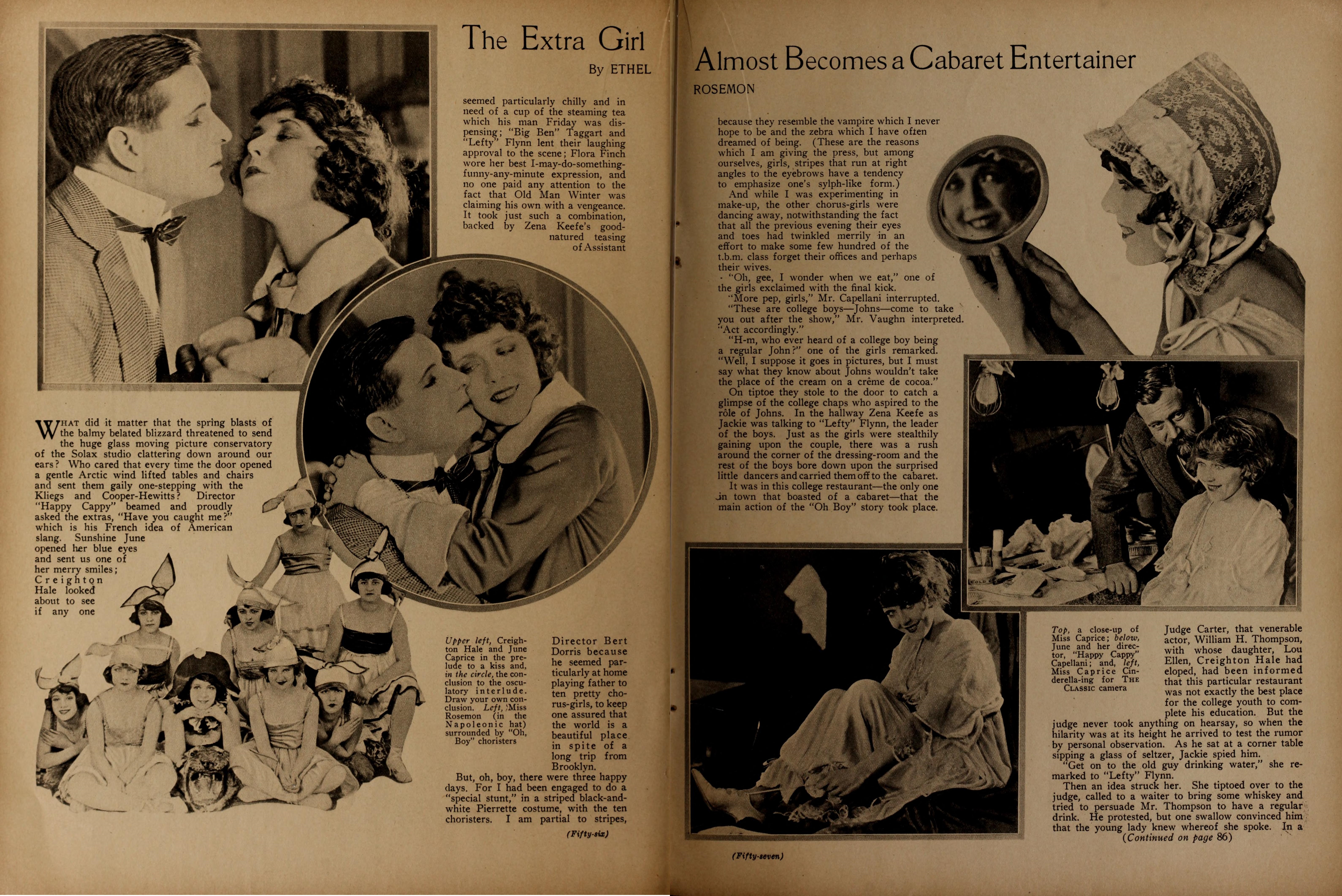

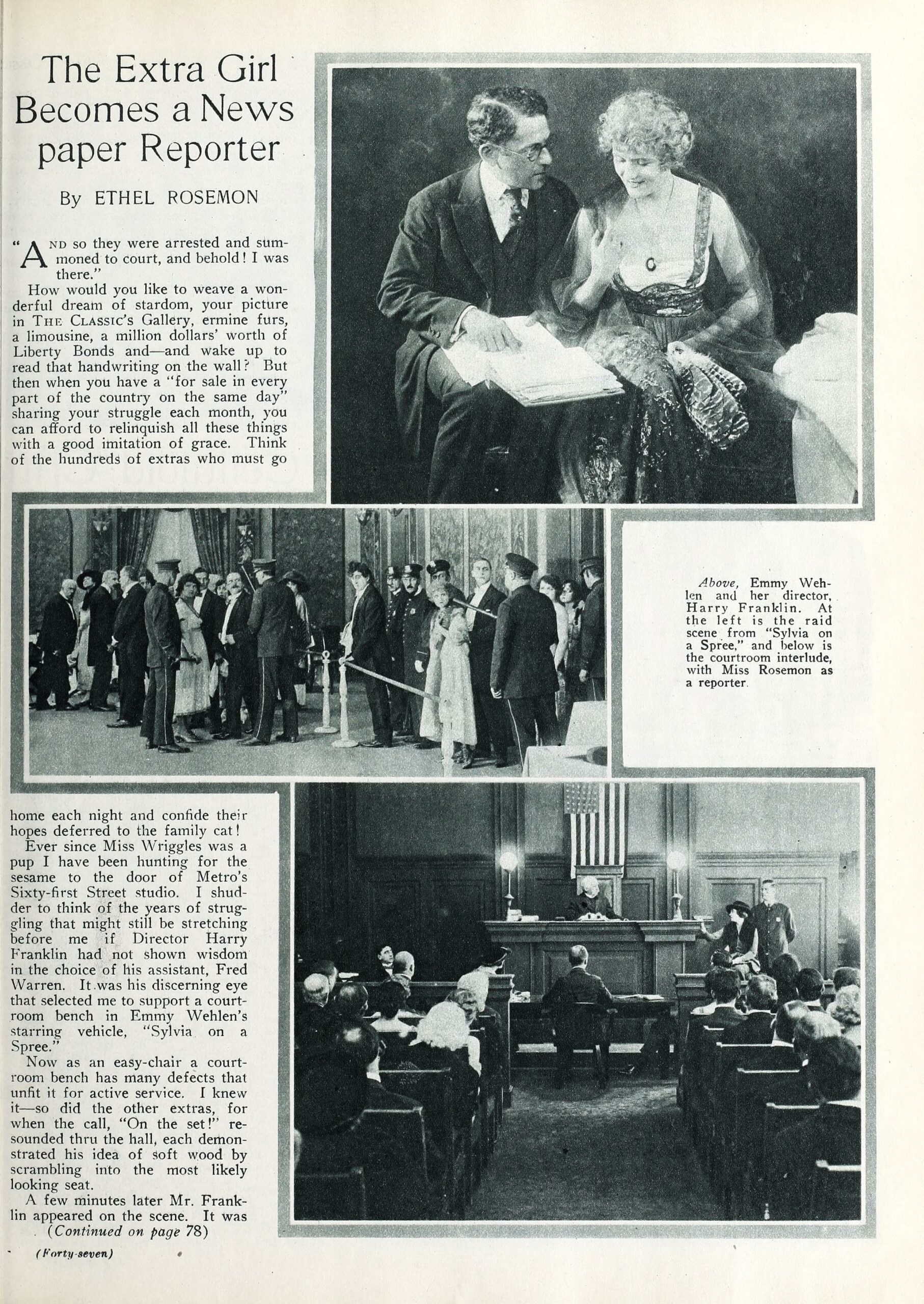

Ethel Rosemon was right in the middle of this action as reporter and actress. She combined both in a series of articles she wrote on life as a movie extra. She was sent on assignment by Motion Picture Classic magazine in 1919 to anonymously infiltrate studio productions as an extra and report on what she saw. That anonymity was a short-lived gimmick; she was advertised to readers as “The Extra Girl”. The articles gave her writing exposure to a wide audience.

While Ethel’s career was taking off, her father’s was winding down. He became a widower for the second time when Mamie, Ethel’s stepmother, died in 1916. Suffering from ill-health, he retired as a lawyer by the 1920s. He still lived in Brooklyn but occasionally visited Setauket, his birthplace.

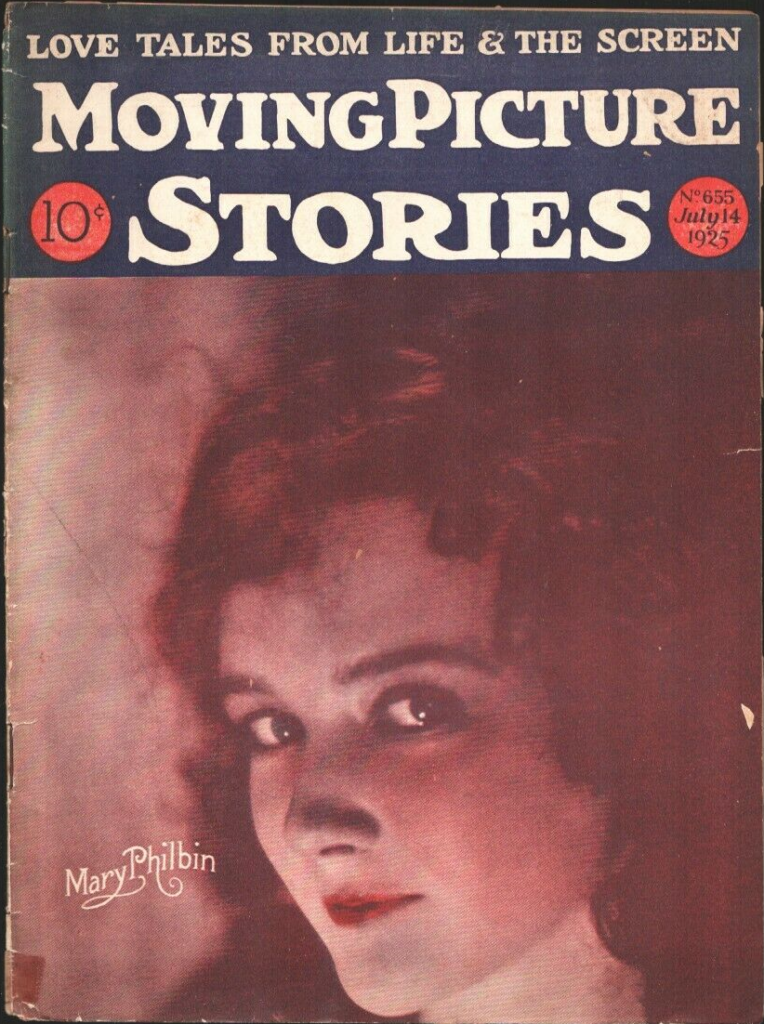

A regular contributor to movie magazines, Ethel converted screenplays to stories for Moving Picture Stories, a Frank Tousey publication launched in 1913. In the first half of the 1920s, Ethel was a frequent contributor to Moving Picture Stories. A 1923 article refers to her stopping acting and writing for Moving Picture Stories while she searched for a dog that ran away from her home after she had she rescued it from a bootblack.

The editor of Moving Picture Stories, Louis Senarens, also edited Mystery Magazine, an oddball detective story pulp that looked and felt like a dime novel and published stories from obscure writers, paying them next to nothing. He may have encouraged Ethel to contribute stories to Mystery Magazine; four of her stories appeared in the magazine in 1920.

Her life changed when a speeding car struck her father on 30 March 1925. Vincent was badly injured and died on 21st May; Ethel may have inherited some money. She formed the Lucky Publishing Corporation and bought Moving Picture Stories, becoming publisher and editor in late 1925.

The previous publisher had been using black and white photos on a red background to give a semblance of color at low cost; she switched to color covers and probably made some changes in the content of the magazine. Circulation was not reported in N. W. Ayer’s annual directory, so I don’t know if the changes were successful in boosting circulation.

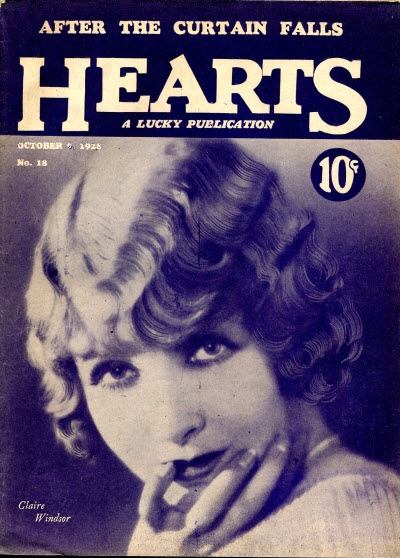

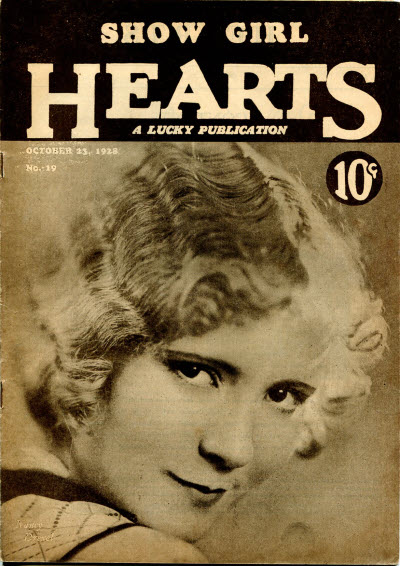

Maybe they were, because Ethel launched another magazine, Heart Throbs, in March 1928. I’ve never seen an issue of this magazine, so what follows is speculation based on looking at the covers. Initial covers featured color photos of screen actresses and boasted of true confession type stories with titles like Intimate Confessions of a Chorus Girl and Ladies of the Night Club. After a few issues, she switched the covers of the magazine to something resembling Moving Picture Stories and changed the title to Hearts.

She was in trouble. In August 1928, she asked the trade journal Author and Journalist(A&J) to stop featuring Hearts as a market:

“We are now using stories from the screen written by our own staff. We think it would be well not to feature our market till we are able to catch up with the present supply. We make it a rule to read every script that comes into this office and to accept every one possible even if it means having some of them entirely rewritten by our own staff.”

What staff? This appeared in the February 1929 issue of A&J:

“I have been away from the office for several weeks and therefore the work, previously very much behind, has slipped even further back. We have been shorthanded since the beginning, and, as I have attempted to read every script that comes into the office, many stories have been kept a length of time I know must seem unreasonable. However, I hope to get out all reports in a very short time.”

Hearts was ceased publication in 1928/1929. Her business was running into trouble just as the Great Depression was starting and credit to small businesses disappeared. She probably sold the magazines to cover her debts. Moving Picture Stories dropped the mention of Lucky Publications from its cover by February 1929, though Ethel Rosemon remained listed as editor. The publisher was now Pal Publications Corporation, of whom I found no trace.

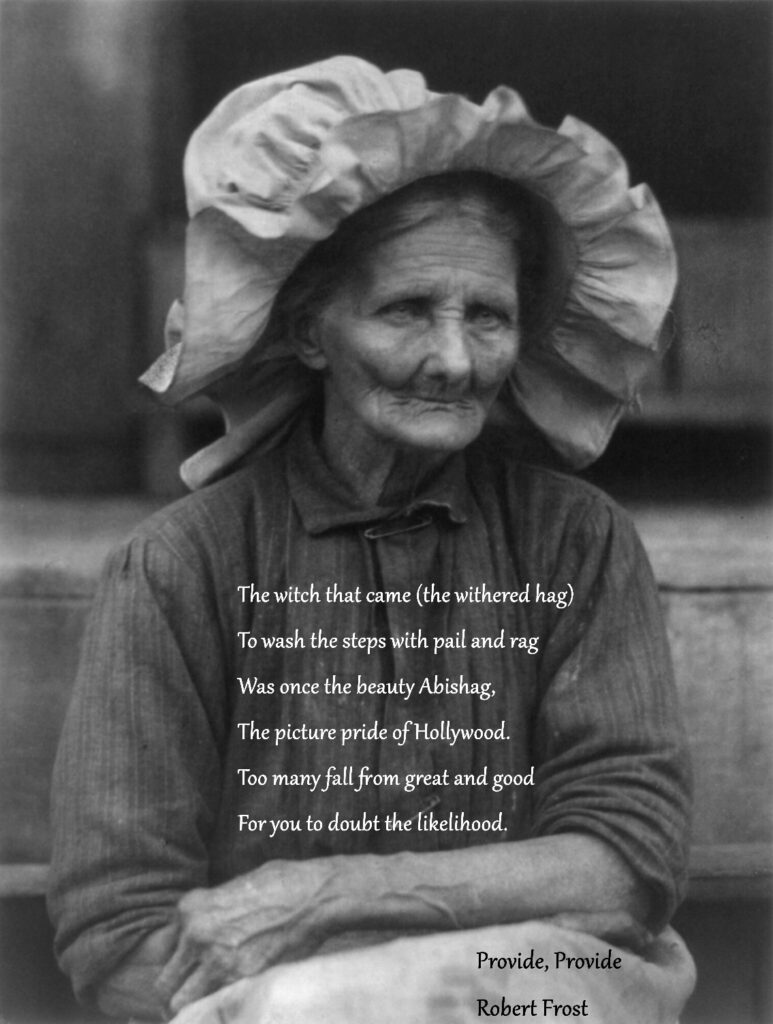

As movie distribution grew broader, the thrill of reading movie plots in magazines no longer thrilled readers. Moving Picture Stories shut down in 1932. Ethel disappeared from public view.

In 1934, the Brooklyn Eagle published a brief article on a theft at her residence, 413 Quincy St, where she had lived for more than two decades. The German shepherd that she had rescued had done nothing to stop her newly engaged servants from stealing her possessions and leaving. Sometime after that, she lost her house. She is mentioned as a classmate who can’t be located in a 1940 Barnard alumni newsletter.

In 1949, she was evicted from her rented house at 111 N. 4th St in Brooklyn along with six rescued mongrels, having lived in a state of siege for 11 days after utilities were cut and policemen waited outside to grab her when she came out. She was described as thin and birdlike; starving may have been more realistic. Her neighbors were supportive, throwing sandwiches and bags of water on her porch for her to grab when the police were inattentive. When she left, the new owners built a gas station on the site.

The neighbors were not supportive the next time. In 1956, she was evicted from her residence at 315 Bridge St after they complained of noise and smells. Twenty-eight dogs were taken by the ASPCA. She tried to find them new homes while she worried about her own.

The last reel of Ethel Rosemon’s own moving story came to an end in February 1966. She was probably buried in a potter’s field. This, then, is her memorial.