Last week, we found Phil Cody looking for an editor. He found the right man. Joseph T. “Cap” Shaw always wanted to be a writer and editor. He was editor of his college newspaper and a track athlete. After graduation, he became a reporter and then worked at a publishing company before joining a textile manufacturer. During World War 1, he organized relief efforts in Czechoslovakia, staying there till 1924. Illness turned him to writing. He came to Black Mask‘s office to submit a story and instead got hired as editor.

Cody’s last issue was October 1926. He left having gotten Hammett to write longer fiction with more developed characters; he could also take some credit for developing Erle Stanley Gardner’s writing skills.

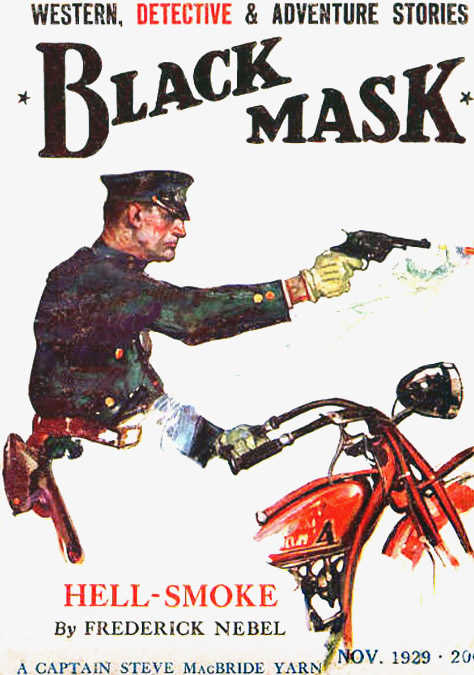

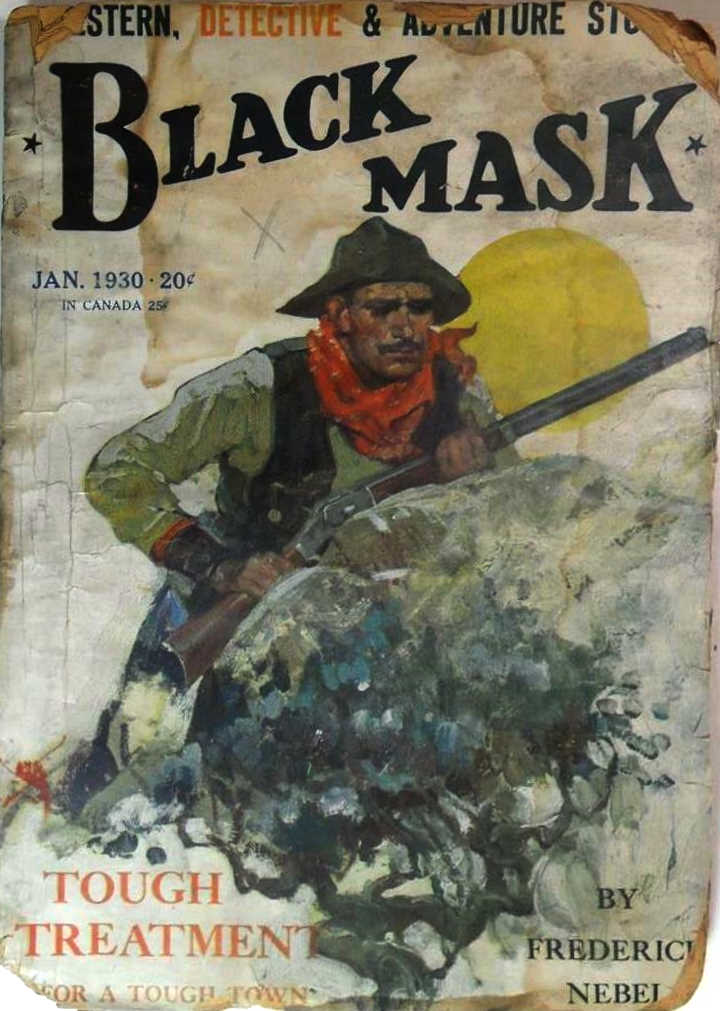

Immediately, Shaw started making changes. The first change was on the covers. The logo changed from “The Black Mask” to just “Black Mask”. The changes were small but in keeping with his plans for the magazine. The curlicues and outlines of the letters were removed and no longer in different colors; they were always black, emphasizing the “Black” in the name. No frills, in short.

The cover illustrations were still western themed, but there were more changes to come.

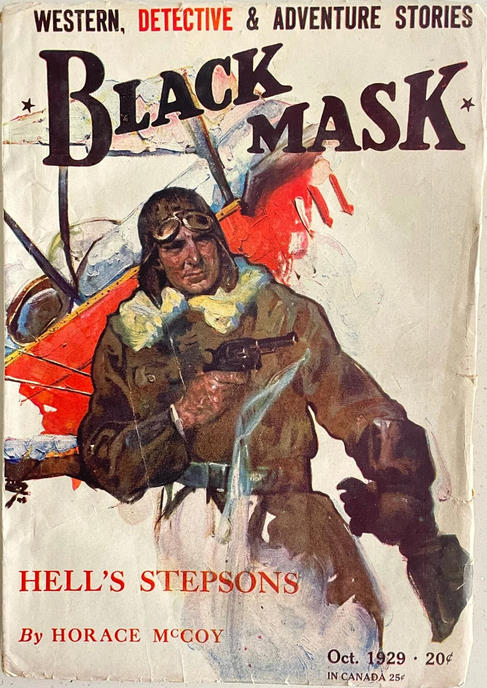

On the content front, he lured Hammett back to the magazine and set about developing a stable of writers who could deliver the kind of no-frills, tough, realistic detective fiction that he wanted to develop. Fred Nebel, Paul Cain, Roger Torrey, W. T. Ballard, Theodore A. Tinsley and Horace McCoy were frequently to be found in the magazine. W. H. B. Kent and Raoul Whitfield contributed western and aviation detective stories, respectively.

(Raymond Chandler, Dwight Babcock, Eric Taylor, Dashiell Hammett, John K. Butler, W. T. Ballard, Horace McCoy and a few others I can’t identify)

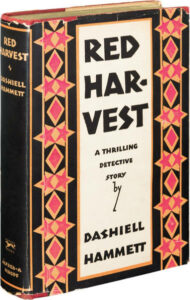

A year after Shaw took over, Hammett published Red Harvest as four stories from November 1927 to February 1928. This was not a coincidence, Shaw had urged Hammett to write novels. When Alfred Knopf published Red Harvest as a hardback, it had a dedication to Shaw.

While the quality of the fiction improved, Shaw also sought to promote the magazine. He arranged tie ins when movies were made from stories either published in Black Mask or by authors who were prominent in the magazine. He gave interviews to reporters, sent free copies of the magazine to newspapers. In punchy editorials he reminded people that prominent authors now publishing detective stories in slick magazines and hardbacks had got their start in Black Mask, where they and similar writers published stories that were transforming the American detective school.

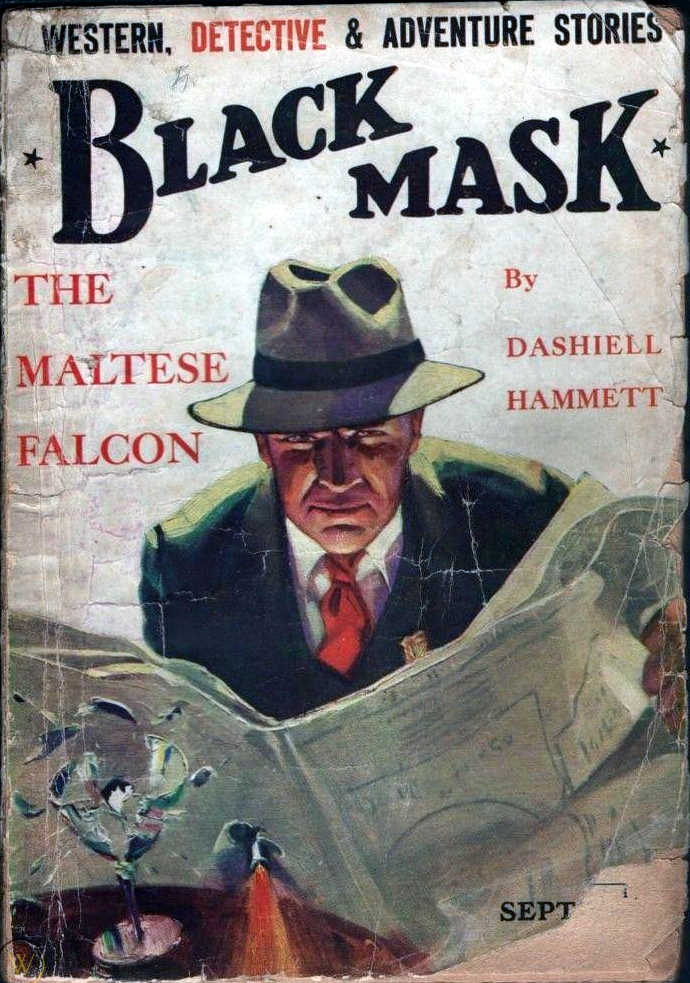

The effect on circulation was stunning. Circulation went from 70,000 to 125,000 in 1929; a very respectable number that matched the circulation of big general fiction pulps like Adventure or Short Stories. The issues containing the serialization of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon were the most widely printed in Black Mask’s history. Considering that, it’s surprising how rare they are today. Other pulps with similar circulations from 1929 are easy to find.

The most underappreciated part of his work must be the changes he brought to Black Mask’s presentation. We’ve already seen the changes to the logo. He was also tweaking the covers. In December 1928, he found the cover artist who would define the visual look of Black Mask. J. W. Schlaikjer’s western cover of a man with a gun in the right hand and firing another with the other hand, done vignette style, had the essential elements of Black Mask that we recognize instantly. Fred Craft and H. C. Murphy were still doing covers, but not for long. Still, Murphy did the iconic Maltese Falcon cover, with a man in a fedora shooting through a newspaper as a bullet shatters a martini glass on a table in front of him. Good reason to remember his name.

Starting with November 1929, two years after Shaw’s first issue, Schlaikjer’s cover of a policeman steering a motorcycle with one hand, aiming a smoking gun ahead of him as he drives, set the tone for the future. The essential elements of Black Mask covers – action, detailed illustrations with plenty of white space, people wearing expressions of grim determination in an action-filled scene and, last but not the least, the man with the smoking gun – had all come together. With white space on the cover, authors’ names could also be given prominence. Schlaikjer would produce almost every cover for the next four years. The October 1931 issue is notable for one change from the formula – instead of a man with a gun, there’s a woman with a gun. Western covers still appeared from time to time.

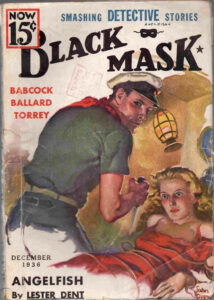

That changed with the July 1933 issue. The subhead now declared Black Mask to have “Gripping, Smashing Detective Stories”. No more western covers. With June 1934, the look changed again. Schlaikjer had done his last cover for the magazine. Non-white background colors and Fred Craft were back, joined by talented artists like John Drew and Rudolph Belarski. But none could produce what Schlaikjer had at his peak.

Interiors got the same treatment. During Shaw’s reign, there was only one artist who did the interior headings for each story. For Black Mask, Arthur Rodman Bowker developed a style unlike his earlier work for Adventure and Smith’s Magazine.

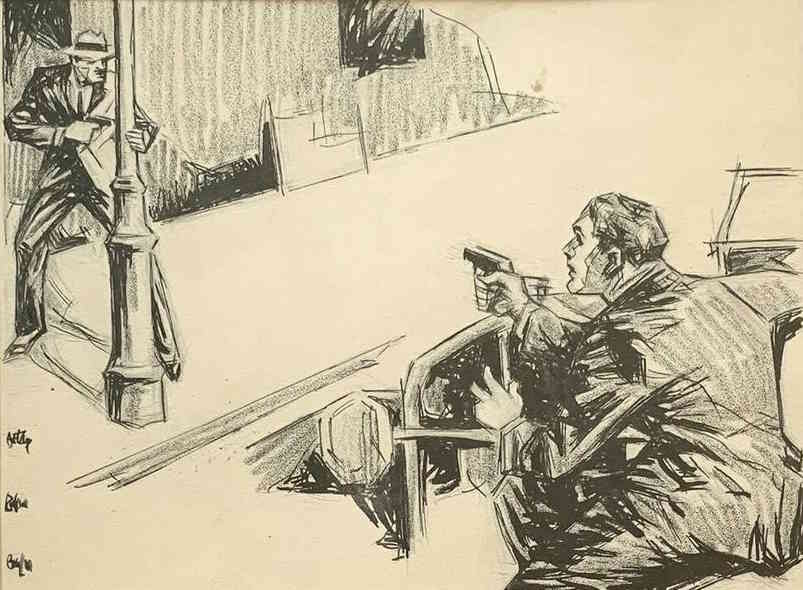

Take a look at this illustration for Too Many Slips, a story by Dwight V. Babcock that appeared in the December 1934 issue. At first glance it seems roughly done: the shading is coarse and the lines are unnaturally straight. The details are so stripped away that it takes a little while to recognize that the man on the right is shooting from behind a car.

(Artist: Arthur Rodman Bowker)

Take another look. The details are stripped away so that your attention goes straight to the two people shooting it out. The drama in the situation is clear, one of them has less cover than the other and is likely to be hit but the other is asking for trouble by poking his head out. There’s suspense for you. Try standing like the guy behind the lamppost. Unless you’re very fit, you can’t maintain that pose for long. This is a moment of frozen action. Look at their expressions. Practically no visible emotion. Drama, Suspense, Action, No Emotion – sounds hard-boiled to me.

The straight, clean lines are minimal and draw less attention to the drawing’s style and more to the scene and the story. Story telling without flash; it’s the perfect visual complement to the staccato rhythms of a hard-boiled Black Mask story.

Just as things were going well for the magazine, and Shaw, competition heated up. Munsey’s Flynn’s Detective Fiction had a new editor, Howard Bloomfield, from 1928. He turned Detective Fiction Weekly around, changing it from a musty looking magazine with fusty fiction to one with sharp covers and varied, fun contents.

The Great Depression hit magazine circulations hard. Magazines shed readers every month; and Black Mask was one of the hardest hit. Circulation dropped to around 70,000 copies an issue in 1931, the level at which it had been when Shaw had taken over. Coupled with a price decrease to 15 cents in 1934, the magazine must have been losing money fast.

You’d have thought, that having found an editor who doubled the magazine’s circulation, Warner would leave the job to Shaw and let him get it back on track. You’d be wrong. Warner kept interfering with Shaw – he suggested dropping Hammett; got rid of Raoul Whitfield, who moved on to Cosmopolitan and was successful there; rejected Fred Nebel’s story, which became Nebel’s last submission to Black Mask and also rejected Erle Stanley Gardner’s successor to the Ken Corning series. Which might have been Perry Mason.

Differences between Shaw and Warner kept increasing till Shaw, faced with reducing pay rates for his writers and taking a deep salary cut, made the decision to leave. Shaw’s last hurrah was the two Oscar Sail stories written by Lester Dent (the writer behind Doc Savage), published in the October and December 1936 issues. Dent loved working with Shaw, and left with him. The hard-boiled era of Black Mask was over with his last edited issue, December 1936.

Warner wanted more sales. He turned to an editor he trusted, one who had worked for him for the last four years and managed to retain readers from 1929 to 1936 despite the Depression.

Next week: Hard Times

For more on Black Mask and Joseph Shaw, there is an excellent book titled Joseph T. Shaw, The Man Behind Black Mask by Milton Shaw, grandson of Joe Shaw. It’s available on amazon and from Steegerbooks.com.

Shaw was one of the great pulp editors, along with Arthur Sullivant Hoffman of Adventure, Joseph Campbell of Astounding and Unknown, Farnsworth Wright of Weird Tales, Howard Bloomfield of DFW and Adventure, Ken White of Black Mask and Adventure, Charles Agnew MacLean of The Popular Magazine, Sam Merwin of Startling and Thrilling Wonder, Daisy Bacon of Love Story and Detective Story, and so many others.

The above editors are just some of the good editors that made the pulps so successful.

Agree that Shaw was a great editor, one who shaped a literary genre by creating a magazine that gave fullest expression to hardboiled crime. Most reviews of his tenure focus on the writing. I thought it was time he got credit for the other, more subtle, changes.