John A. Saxon (1886-1947) wrote mostly western and detective stories in a writing career that spanned more than twenty five years. Working as a law clerk, he wrote stories on the side and was part of a California writing circle that included Robert Leslie Bellem, the author of the Dan Turner stories.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

For thirty-six years the writer of this article has been selling “pulp”. As a member of the old New York World staff in New York in 1909, he wrote and sold his first story, “The Mantle of O’Hara”, to BLUEBOOK.

He has sold more than 1,200 shorts, novelettes and lead novels to practically every pulp magazine published in the last three and a half decades. Three-fourths of his total wordage of over 6,000.000 has been “Westerns”.

In that space of time he has weathered half a dozen “trends” and has been instrumental in helping some of them occur.

Except for five years devoted exclusively to writing, he has been engaged in his daily work as an official of the Superior Courts of California for thirty years.

I SUPPOSE at one time or another we have all said to ourselves: “I’d like to be an editor. They don’t know a good story when they see one.”

Let us waft the magic wand and for the nonce become an editor.

The morning mail has just arrived, and upon your desk you find a stack of manuscripts six inches high. You pick up the first one and read:

“Jim Bridger reined his fiery, foam-flecked steed back upon its haunches.

He pulled his trusty rifle from its scabbard. The red-skins were edging in from every side.

“Flinging himself from the saddle, Jim Bridger fired once— twice—and then again.

Three of the howling savages bit the dust, never again to challenge the supremacy of the white man nor the unerring aim of Jim Bridger’s Winchester.”

What did I hear you say? “Oh brother!” You’d reach for a rejection slip and send it back?

Wait a minute. We didn’t say during what period you were acting as an editor, did we?

“Nobody ever wrote such tripe,” you say? If you had been an editor thirty years ago and the rest of the yarn had held up, you would have put a voucher through for the writer of that wild-eyed mess. I know.

I wrote it and I got paid for it. I’ll agree that it now sounds “stinko.” But thirty years ago it was hot stuff. It wasn’t “corn” in those days.

The beginnings of the present day Western story are clouded in dust, legend and obscurity. It is difficult to tell just when the embellished fact stories of the late 70’s began to be straight fiction.

In his interesting book “Belle Starr” Burton Rascoe, old time Oklahoma sheriff, says that as far back as the late 1850’s the Police Gazette was running “outlaw” stories, supposedly based upon fact and using real names, but dressed up by New York writers who believed there were still Indians roaming the streets of Chicago scalping the citizens.

These were the lurid and entirely untrue stories of the notorious “Billy the Kid,” Wesley Hardin, Sam Bass and the Thompson brothers, says Mr. Rascoe.

Authentic facts concerning those days are hard to obtain, as I well know, having made a study of the subject for a quarter of a century.

As far as I am able to learn—and it is ten to one someone will dispute it, the readers of W. D. being a challenging lot—the so-called “fictionized Western story” came into being sometime in the 70’s.

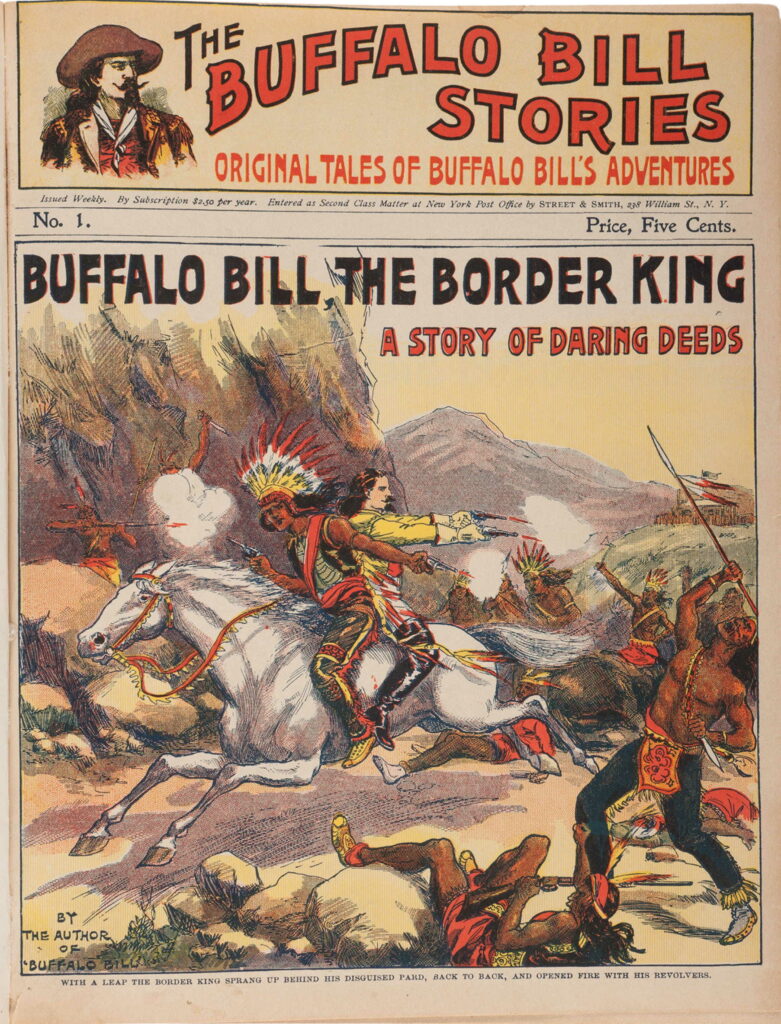

A highly imaginative New York newspaper man whose name was Judson, but who wrote under the pseudonym of “Ned Buntline,” conceived the idea of immortal, izing the great west by doing a weekly novelette of 20,000 words, using as a protagonist some actual, well known person. The book was to be in flat format similar to our present day “Comics.”

Buntline wanted an authentic character upon whom he could pin great deeds of “derrindo.”

At that time there was an army officer in Kansas whose exploits as an Indian fighter had made the eastern newspaper headlines, much as our Major Bong did during the early days of the present war with Japan.

Buntline made a special trip from New York to the Great Plains for the sole purpose of inducing this army officer to become the protagonist of the proposed stories.

The army officer would have none of it and tossed Buntlin for what the movies call a “pratt-fall.”

Buntline was not discouraged. (Ever see a newspaper reporter who was?) He went back again and asked the army man if he wouldn’t—who would?

Perhaps admiring Buntline’s persistence, the army man referred him to one Bill Cody, a buffalo hunter for the various construction and army camps. Cody had been a pony express rider, a scout and Indian fighter, and, although he had experienced a number of hair-raising exploits, he was just a “meat-man” and little known otherwise.

Cody lent a receptive ear to Buntline’s proposition, inasmuch as he was to share in the profits of the venture. He consented to become the protagonist of Buntline’s suggested stories.

Legend has it that it was then and there Cody became “Buffalo Bill,” being so named by Buntline.

Thus was born the Buffalo Bill Weekly, which enjoyed almost as phenomenal a circulation as our present day Superman.

Cody was a natural “ham,” as they say in the theatrical world. He began to live up to the mythical exploits Buntline invented and printed as gospel truth. He dressed himself as Buntline’s artists depicted him—wide brimmed Stetson, leather boots that reached above the knees, soft white silk shirt and the famous Windsor tie that became, in later years, Cody’s trademark.

Upon the basis of the publicity created for him by Buntline and the Buffalo Bill stories, aided monetarily by the royalties that rolled in from Buntline for the use of his name, Cody organized and became world renowned as the star of BUFFALO BILL’S WILD WEST SHOW. He toured America and Europe, was introduced to royalty, became an historical figure all because of the exploits which were pure invention on the part of Ned Buntline.

Thus, I am told, the Actionized form of the Western story was born, based partly on fact, but mostly upon imagination.

Buntline became so famous as a portrayer of the Wild West, that the Colt’s Arms Company put out a special gun in his honor called “The Buntline Special.”

Ned Buntline’s Buffalo Bill stories soon had a host of imitators. At the turn of the century we had Diamond Dick, the creation of the late William Wallace Cook, who later compiled “Plotto”

Diamond Dick was a sort of little Lord Fauntleroy with guns. He was depicted as wearing long golden hair, dressing himself in black velvet with gold braid, and the buttons of his jacket were diamonds the size of walnuts. He was a devil with the ladies and a hell-cat with his guns.

Then we had The James Boys, The Dalton Boys, The Younger Boys, Calamity Jane, Belle Starr, the Female Jesse James —just to name a few of the nickel weeklies. Although purportedly based on fact and using real names, they were one hundred per cent fiction.

For those who liked a little less blood with their thunder, we had Frank Merriwell, written by “Burt L. Standish,” in reality Gilbert Patten, who died a few weeks ago in San Diego at a ripe old age. Then, too, we had the Fred Feamot stories, and a host of others. They all covered the adventure field.

About that time up popped the Nick Carter Weekly, Old King Brady and others, forerunners of our present day Detective story magazines.

After the breakdown of the five-cent “blood and thunder,” Western yarns began to appear in regular magazines as one of several stories on various subjects. Golden

Argosy, founded in 1882 as a general family magazine, ran a number of Westerns, and when it became Argosy, in the familiar yellow cover, the book carried many more.

By this time the fiction formula had been fixed and it remained so until about 1925-1930. There was always the 100 per cent hero, a villain at whom the readers could hiss, a heroine with soul of purest white.

Plots were stereotyped. The protagonists were always what later day editors called “gun-dummies.” Action!! Action!! Action!! was the constant cry.

Any story that didn’t have a killing on the second page—it didn’t matter who it was or why he was killed—was doomed to instant rejection. No wonder that old-time Western , writer “Chuck” Martin has his own “boot-hill” on his ranch, where each of the many characters killed off in his stories has its head-stone. For a picture of this odd cemetery, see The Writer’s Year Book for 1942.

The pattern having been set, the Western story rolled its merry way for many years without change.

THE greatest single influence in retarding the development of the Western story were the hide-bound traditions of the editors and publishers who bought them. Most of them knew little about the West and cared less. They were governed by one creed—Circulation. If the editor had an idea* for improving the type of stories, he was usually met by the objection of the publisher: “Why? We have printed the same story for years. Our circulation is building up. Why change? It’s what the public wants. We can’t afford to experiment.”

So, they didn’t experiment—at least not for a good many years.

Prominent among the causes for making no changes were a lot of false concepts. Here are a few of them that have been pretty much exploded in present day Western fiction, although a lot of writers and editors still cling to them religiously:

“All killers have blue eyes .”

Bunk! In my law work I have met and talked with dozens of killers and so-called “bad-men.” As many had black, brown, gray, and green eyes as had blue.

“He shot from the hip with deadly accuracy.”

Baloney! You can’t believe what you see in the movies. I’ve heard of men shooting from the hip, but they never hit anything smaller than the side of a barn.

“He fanned his six gun with lightning speed, and three men died.”

Oh, yeah? I once asked the great gunman Wyatt Earp if he had ever seen a man “fan” a gun and hit anything. He said “no” in such a way as to leave no doubt as to what he thought of the idea.

“With a gun in each hand he outlined his initials in the mirror back of the bar.”

I once saw an expert pistol shot try that stunt from a rest. He couldn’t even come close to it. Imagine doing it free-hand! It’s just some more of that stuff that makes the grass grow so high in Texas.

“A blazing six gun in each hand,” etc.

Even the movies believe that one. It is a hold-over from the days of Buffalo Bill. The fact of the matter is that there were men who carried two guns, but they used one at a time. They were experts in “the border shift,” firing the right hand gun until it was empty, then quickly shifting a full gun from the left hand to the right. But, how many illustrations have I seen where the hero was shown dashing through the main street with the reins in his teeth, (a fine way to lose a couple of them) and blazing sudden death with a gun in each hand.

In connection with this “shooting from horseback” thing I am reminded of a beautiful stink that came out in the public press when I was a kid. It was in connection with Buffalo Bill’s shooting in his Wild West Show. Old Bill Cody would come galloping into the arena, a gaudily painted Indian ahead of him on a speeding pony. On his arm the Indian carried a basket of clay balls. Riding around Cody the Indian would toss the balls in the air. Ever notice the measured pace of a circus horse while acrobats perform upon his back? That was the “galloping” of Buffalo Bill’s white charger.

Oh, sure, Bill used to hit ’em. He’d knock ’em off at a great rate.

One day in Minneapolis his Winchester missed fire. Nothing daunted, Bill jacked the dead shell out of his gun and it fell in front of an inquisitive newspaper reporter. Curious, as all newspaper reporters are, the reporter took a knife and opened the Winchester shell. It was filled with fine bird shot! He printed the story and they say Bill tried for two days to locate that reporter.

LET me interpolate something here as part of the background of this article, one of the most historical characters of the old west was Lotta Crabtree, the western music hall songbird. She was the darling of the camps for years. Known as “Lotta’s Fountain,” a monument to her memory stands on Market street in San Francisco to this day. She sang many times at the old “Bird Cage Theatre” in Tombstone, Arizona. (The last time I was in Tombstone a few years ago, the “Bird Cage” was a storehouse for a feed and fuel house.)

When she died, Lotta left an estate of nearly a million dollars. In retirement, she was living in Boston when she passed on.

There was a contest over her estate and one of the questions that came up concerned a purported heir, supposed to be the child of her brother, who had lived in Tombstone in the early days.

In connection with my law work, the Massachussetts Surrogate Court appointed me as Special Commissioner for the State of California, to take the testimony of Wyatt Earp, who had been marshal of Tombstone at the time Lotta’s brother lived there.

Thus I made the acquaintance of Wyatt Earp, a friendship that endured until his death in Los Angeles January 23rd, 1929.

At the time I met Wyatt Earp he was over seventy, but had the appearance of a much younger man. As a writer of Westerns I tried to sound him out concerning the “early days” but he was never a loquacious man and it was hard to get him to talk. Even during the taking of his testimony in the Crabtree case I had trouble getting him to say more than “yes” or “no” and that went on for days.

However, one time I did get him to open up a little on the subject of western stories, many of which concerned his own experiences. I had asked if he had ever read any of them. He looked at me for a long time and finally said: “Yes.”

“What do you think of them?” I asked.

“If any man had ever acted as most of these so-called gunmen are portrayed in the westerns I have read,” said the great marshal, “they would have been killed off in twenty-four hours. People would have considered them too crazy to be allowed to run loose.”

Which was a long speech for Wyatt.

Wyatt Earp never carried a gun unless he went out to make an arrest or expected trouble in the next few minutes. Maybe that is why he lived to be eighty years old.

WHEN did Westerns outgrow their swaddling clothes?

The early pattern became rigid as a vise and it remained so until about 1925-1930.

Up to that time, with minor exceptions, we had pretty much the same old “bang- bang” with lots of “action.”

However, there were some editors who were beginning to realize that their readers were tiring of the tripe about the wandering cowman, the crooked foreman, the hero on the wrong side of the law, the crooked sheriff, the banker who held the mortgage, the rustler, and above all (although to some extent still persisting) the returning cowboy who comes back from afar to avenge the death of his father, brother, or friend, or who returns because his father, brother, or friend, is in a jam. That one dies hard. You can find it in nearly every book you pick up today. It’s a classic “situation.”

Editor Blackwell of Street and Smith was one of the first to ask: “Why must the hero always be a cowboy?”

He got an answer to that from H. Bedford Jones who began sending him the “Medicine Dan” stories which ran for a long time.

“Medicine Dan” was a wandering, self-constituted protector of the rights of the oppressed, with an eye always cocked toward his own gain so long as it came from the undoing of the villain. He would come into town with his “medicine wagon” from which he peddled all sorts of nostrums for man and beast. Before long he managed to get embroiled in some sort of local fracas, straighten everything out, punish the guilty and be gone before sun-up, to appear again in the following month’s issue.

I remember when “BJ” decided to kill Dan off. I was living on the opposite side of the Indian reservation from Jones, up at Palm Springs. It was sometime around 1932. One day he told me that he had written Street and Smith there would be no more “Medicine Dan” stories; that he was tired of doing them.

Editor Blackwell wrote: “Hell, BJ, you can’t do this to me. Dan is a fixture. He will go on forever.”

Jones, in his laconic way advised Blackwell: “Not under my name he will not. I’m weary of these fakeroo westerns about things that never happened and never could, happen.”

And so, “Medicine Dan” died.

“B.J.” told me at the time he would never write another Western. So far as I know he rarely has, preferring to devote his entire writing to adventure stories for Blue Book and Short Stories.

I was getting pretty tired of “bang-bang” and took Jones’ words very much to heart.

Western pulp fiction began to swing toward what some have called the “realistic” story. Walt Coburn topped the field in this division for years. His characters are real. His backgrounds are real. While some of his stories still feature a lot of “bang-bang” they differ from the old type in that there is always a reason for the shooting.

During this period Erle Stanley Gardner came up pretty fast. Erle had been district attorney of Ventura County and leaned heavily toward the detective story, although he did write a lot of Westerns. Remember his “Road Runner” yarns?

Rogers Terrill and Mike Tilden began querying their writers for what they called “The Emotional Western;” something that appealed to the emotions of the reader rather than having only the thrill of action and gunsmoke.

I believe that Cliff Farrell and myself— and there were probably others—began writing this type of story about the same time.

Harry Olmsted was infiltering this idea into his Indian and Overland trail stories.

Looking for back numbers of pulp magazines is like trying to find somebody who will give you a red coupon. They just naturally “aint”—so I cannot check on any of Cliff’s stuff. As a result I shall have to rely upon memory, and my own files.

One of the first of my “non-bang-bang” stories was an 18.000 worder I wrote for Five Novels, entitled “Range Branded.”

It got into print in this manner. I was having lunch with the late Florence Mc- Chesney, then editor of Five Novels, and in the course of the conversation I said: “I wish somebody would let me write a story in which about seventy-five less people die and where the protag doesn’t even carry a gun.” ‘

Florence said: “Well, don’t you try that sort of a yarn on me. I won’t buy it, and I’ll probably get hell if I do, but let me see it.”

Eventually she bought and published it. I made my first step in the direction of a goal which I was not to attain for many years—to write and sell a Western story in which the hero didn’t carry a gun, and there was no shooting at all.

Let’s take a look at these dusty files.

“Pfui!” Does that yarn smell. And only twelve years ago.

Dave returns to his home range (here we go again, you will notice—and it’s still going on today) after the murder of his uncle who dies without leaving a will. As the only blood relative Dave is set to inherit. Knowing his uncle wanted a foster daughter to have the property, Dave refuses to take it. (He’s in love with the gal of course.) She meets him coldly, explains that feeling runs high against him in the valley because many suspect him of killing his uncle, although Dave at the time was “far, far, away.” He wants to investigate but she tells him he will only make trouble, especially unless he hands up his guns.

So, for the rest of the story, we have Dave branded as a coward for giving up his guns, he having shucked them at the insistence of the girl; the public at large believing that he is hiding behind the old Western code that “nobody shoots an unarmed man.” However, he is still able to use his fists and the necessary “action” is covered in that manner.

Toward the very last of the story we let him have his guns back, the girl releasing him from his promise, and, after 17,000 words mind you, we finally have a gun- fight, the real villain is killed, he gets the girl, etc., etc.

In my humble opinion the only reason that story held together was because the reader sensed that sooner or later Dave was going to get his guns back, which, I think, made the story much more effective than if he had “swash-buckled” all the way through. It wasn’t so hot, I’ll admit, but it was a step in the direction I had charted.

By now, Cliff Farrell was really going to town with his “emotional” stuff in Dime, and Star. They were “sob-story” yarns and Cliff handled them nicely—the sort of story where the writer tries to leave you with a tear in your eye and feeling damned sorry for somebody.

WITH the help of my New York agent, “Auggie” Lenniger, to whom I’m afraid I have always been a pain in the neck, being strictly of the “non-conformist” type myself, I hopped on the band-wagon and began to try to “out-sob” Cliff.

I started the “Gunsmoke” series for Jack Burr of Street and Smith’s Western Story, at the same time doing a lot of the old-type Westerns for other books that were inclined to let some other publisher do the experimental work.

Let’s have a peek at some of those Gunsmoke stories and try to figure out what made them click with a hard-boiled editor like Jack Burr. I don’t know how many of them I wrote for Jack. There must have been twenty’.

Here’s one grabbed at random from the file—“Gunsmoke Homecoming.” In 1935 a lot of us were trying to get away from the “bang-bang” stuff and having tough going. If you wanted to sell, you wrote what they wanted. Looking this yarn over I find that I went pretty far with it. There are two pages of introspective stuff right at the start. I’m afraid Burr cocked an inquisitive eyebrow, but he bought it.

I was still sticking to the “man who came back” formula, but this time the hero’s benefactor has been killed, after the protag left town because he was mixed up in a rustler killing. He has left a note for his sweetheart saying:

|

I’m going away for a while. | It’s best this way. |

| There’s been trouble. | Don’t ever believe me or |

| Dode killed the Walking H. man. |

The compositor crossed me up when that note got into print. The gag was that the villain had torn the note in half so that it left the first six words of the first sentence, the first three of the third, the first five of the last line, which made it read:

|

I’m going away for a while. |

|

There’s been trouble. |

|

Dode killed the Walking H. man. |

Inasmuch as Dode was the girl’s brother you can see the complications. The way it came out in print it looked pretty silly— but it got by.

Skimming through this yarn I find only one shot fired at the very end.

Hurrying through several of the Gun-smoke stories I can detect a distinct leaning toward the psychological development of character, a deliberate underplaying of violence, and an almost total absence of gunplay.

During this same period I was writing a lot of stuff for Mike Tilden and Rogers Terrill of Dime, Star, Ace-High, etc.

Popular Publications was beginning to like the “emotional” type of story, so I stuck my neck out on it and wrote a thing called “Greater Than Gunflame” It came pretty close to being a sacrificial love story.

The young sheriff saves the life of his deputy in a gun-fight (off stage) but the deputy gets a shot in the leg and is crippled for life. He feels the deepest gratitude toward the sheriff for saving him from being killed.

The deputy and the sheriff are both in love with the same girl, but the deputy, because of his crippled condition, refuses to tell the girl of his love. The sheriff keeps him on as jailer. The sheriff, not knowing how the deputy feels about the girl, tells him that he is going to a dance that night and is going to ask the girl to marry him. (See how badly you can make the reader feel about the poor deputy who can no longer dance?)

The deputy, after the sheriff has taken the girl to the dance, learns that the man who crippled him is back in the country to “get” the sheriff, and he surmises the attack will be made at the school house where the dance is being held.

The deputy cannot walk nor ride a “hoss” and so he “drags” himself to the dance. (More sob stuff). Surreptitiously he gets the sheriff’s black and white calfskin vest, which is the sheriff’s trade-mark, puts it on and forces himself to walk upright out into the moonlight to draw the fire of the hidden killer and take his chances on killing the dirty villain so his pal can marry the gal.

“God! If he can just take those few steps—”

I milked that situation dry, and felt damned sorry for the poor deputy while I was doing it.

The deputy shoots the villain (two shots in the story this time). The girl learns what has happened. The deputy is wounded. The girl rushes to his side. The sheriff tells him he has been turned down, that it is really the deputy the girl cares for, bum leg and all. “Ain’t love wunnerful?”

Now let’s all be honest with ourselves. That’s pretty “drippy goo” for a hell-to- larrup Western isn’t it? Of course I am picking out extreme cases to illustrate how hard I was trying to keep up with the trend and get ahead of it if I could.

Lenniger used to give me the very devil at times for sending him “trial balloons” that were completely off-trail. I was forever experimenting to see how far I could go and get away with it.

ANOTHER tabu that used to gravel my innards was: “You can’t have a Mexican for a protagonist”

“Owlhoot Swamper,” published in Ace High, blew that one down for me.

A Mexican bandit comes to a cow-town planning a bank robbery. The only job he can get while he “cases the joint” is that of a swamper in a saloon—the lad who cleans the goboons and does all the dirty work. Despite the fact that he is un Caballero as all Mexicans consider themselves, he incurs the jibes, the insults, the abuse of the men of this greaser-hating town. Ah! He will show them. Is he not the great El Nino, the Mexican Kid, the bandit, the greatest gunman in all “May- heeko?”

He has but one friend, a small toddler of five, the son of the town’s milliner, a child too young to know the meaning of race prejudice. El Nino adores the kid.

Comes the great day. His pals stampede a herd of cattle through the town, hoping in the confusion to rob the bank.

But the child, seeing his friend El Nino on the opposite side of the street, starts across in front of the onrushing cattle.

The greatest exponent of la pistola south of the Rio Grande doesn’t hesitate. The child is too far away and the cattle too dose for him to reach the kid, so he takes his stance in the middle of the street and shoots down the leading steers before they reach the baby, thus forming a barricade and causing them to swerve around the roungster. The child is safe, but El Nino, his gun empty, is trampled to death before he can escape.

The sheriff, after the bandit is dead, recognizes him from a reward poster, but tears it up without disclosing the identity of our now heroic Mexicano. The towns-people, never knowing that they are honoring a bandit, give El Nino a great funeral.

Still another tabu—made to be broken as they all were, was to the effect: “You can’t write a first person Western unless it is comedy”

I was able to knock that one over— others have done it too—in a story called “Empty Holsters” in Dime Western.

In this one, the protag is a young cattleman who is given probation in a shooting scrape upon condition that he never again carry guns.

He too, gets pushed around until finally one day he shows up in town wearing (apparently) his old pearl handled .45s swinging at his hips.

By pure bluff, he outwits the villain by daring him to draw. The villain, seeing what he thinks are the guns of our hero, and well knowing his ability to use them, refuses to draw, backs water, and is laughed out of town.

The sheriff arrests the hero for violating the terms of his probation. Aint he totin’ guns, by hell?

Nope, he aint. He has taken the butts off his old guns, fastened them to wooden dummies, shoved them into his holsters and bluffed the villain to a fare-thee-well.

All of this was told from the viewpoint of the hero’s older friend and mentor.

And so it went from year to year. Stories of gamblers, cattle-drives, cattle-trains, store-keepers, doctors, and what have you. Girl view-point stories, school-teachers, ranch-girls, girl-gamblers, milliners, waitresses, ad lib, and ad nauseam.

I think Bob Bellem and I hit the top on lay-characters, when together we wrote a lead novel for Leo Margulies where the protagonist was a veterinary, and the villain was injecting fever into herds of cattle because he wanted to buy the cattle-land for a railroad. There was everything in it but the kitchen stove. The hero sent back east for serum. The villain side-tracked it. The hero went after it and the villain set a prairie-fire.

Oh me, oh my—such fun.

In 1941, I got thoroughly fed up with Westerns and quit writing them. There was only one thing I hadn’t accomplished and that was to write a Western story where the hero didn’t carry a gun, and in which not a shot was fired. I had about given up hope of accomplishing it. Auggie Lenniger said I was nuts, and he was probably right.

So I switched entirely to detective stories and nothing else.

YEAR ago when I came back to the Western field it had changed once more.

For several years the editors had been yelling for more characterization.

Tommy Blackburn was going like a house afire with his “Christopher Defevre” stories about the old Shakesperean actor who was roaming the country with a show- troupe and getting into about the same sort of adventures as old “Medicine Dan” did years ago.

Cliff Farrell, too, had become “fed-up” and had gone back to one of the Hearst newspapers as night editor. He had done but little writing for several years, when all of a sudden he broke into the slicks with “Fiddlefoot,” in S.E.P.

But the old-timers can’t stay away. Cliff is writing again now for Dime and Star.

Once more I had to catch up with the parade. How far, I asked myself, had the Western progressed? How far was I behind the procession?

My first try resulted in “Vanguard of the Steel Trail Legion” which appeared in the October 1944 Ace High.

I threw the book at them in the way of characterization, slow tempo, little or no gun-play and made my hero—of all things —a telegraph-operator who had been a spy in the Union Army during the civil war. There was a land fight out in the west and the United’ States Land Office wanted it stopped. The question was which way would the railroad pass through a certain portion of the state. Our hero, secretly, of course, represented the government.

It was one of those “brother-against- brothcr” things that we had years ago when William Gillette played “Secret Service” on the stage. (Or wouldn’t you young fellers remember?) The bad man was the hero’s brother.

I caught onto the trend quickly. Minimize the gun play but keep the threat of the gun there at all times. The threat of impending action, and the threat of gunplay is much more effective than the actual happening thereof.

I did a couple of more and felt that I was back in the saddle.

Having done a lot of girl viewpoint stuff in past years, I wondered how the new formula would work on that media— a minimum of action, lots of characterization.

A short called “Shifting Sands” was the result, and it sold to Toronto Star, bringing a slick word rate that surprised me, and a featured position that pleased me no end. (Toronto Star, December 30, 1944.)

Back to the man’s viewpoint again I wrote “The Outcast of Cliff City, and I went whole-hog on it. The hero was a railroad man, an ex-convict, and the former member of a gang of bandits. He was married, had his wife with him, and shattering the greatest tabu of Western pulp fiction, his wife was expecting. It sold to Ten Story Western, and I suddenly realized that here, after long last, I had sold a story in which the hero didn’t have a gun, no shots were fired (except off stage) and motherhood was no longer something to whisper about.

Walker Tompkins, who used to turn out reams of stuff for Wild West Weekly, the Street and Smith book, wrote me a letter from his army post in England saying: “I don’t believe it! Shades of Blackwell! A pregnant woman in a Western Story!!! Buy yourself a drink with my compliments.”

I did. I felt that I had finally arrived.

Thirty-six years of it and 6,000,000 words! It has been a lot of fun. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.

What’s going to be the next general change in trend? Darned if I know. But, I’m going to have myself a swell time trying to figure it out and beat somebody else to it if I can. There’ll be a change you can bet on that. That’s what has made this racket interesting for the last 15 years.

The editor of W. D. has asked me to say something about what I think is holding back the future development of the Western story.

I have proved to myself that in the past few years editors have become pretty receptive to anything new IF YOU DO IT IN AN INTERESTING MANNER. The old hide-bound traditions as to what you can and cannot do in a Western story have been pretty well shattered. I like to kid myself that to some small extent I have had a hand in busting them.

Two closing bits of advice to the younger writers:

If you expect to last in this game, change your pace ever)– so often. Don’t let yourself get “rutted” doing any type of story. If you do, the first thing you know you’ll be telling yourself: “I’m written out!”

To those of you who feel that you are approaching that condition, consider the words of a man who has written more pulp than most of the rest of us put together, and is still going strong—H. Bedford Jones.

“No man is written out so long as he can THINK. When he can no longer do that, he’s the same as dead anyway, so what the hell difference does it make?

May you have as much fun pounding out your yarns as I have had.

John Saxon mentions that you cannot find back issues of pulp magazines, so he had to rely on his own files of stories that he had written and his memory. This of course is utter nonsense. As a collector many decades after Saxon died, I’ve put together extensive runs of just about all the major pulp titles, including some magazine issues that are now over a hundred years old like All Story, Argosy, The Popular, Adventure, Short Stories, etc. Even Western Story I have over 1250 issues lacking around 10 dates.

And I’m not the only collector that has done this. I recall Raymond Chandler in his Letters telling a reader in the forties that trying to find back issues of his stories was practically impossible. Not true. In the 1970’s I managed to find all Chandler’s work in Black Mask, Dime Detective, etc and the prices were not that high.

Fascinating article but I have to admit not liking John Saxon’s fiction that much.

Saxon wasn’t looking hard enough, because California definitely has its share of pulps in the wild. His fiction may not be very readable today, but he’s mostly right about the changes that happened in the pulp westerns over time.