For nearly 30 years, Alcatraz was THE prison, the one no one escaped from. Al Capone was held there, as were Machine Gun Kelly, Mickey Cohen and other prominent gangsters. A total of 36 prisoners made 14 escape attempts, two men trying twice. 23 were caught alive, six were shot and killed during their escape, two drowned, and five are listed as “missing and presumed drowned”.

In 1959, when Burt Lancaster was looking around for a story for a prison movie, he received two stories, both of prisoners in Alcatraz. One was Robert Stroud, the Birdman of Alcatraz and the other was Elliott Wood Michener, the Gardener of Alcatraz. This is Elliott’s story.

Elliott’s father, Clarence David Michener, was a mechanical engineer. His mother, Kate Ashley, was a nurse from England. Elliott was born in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, a scenic lakeside summer resort for the rich, on August 24, 1906. Clarence’s job involved considerable travel and caused family friction, leading to a separation in 1908. Kate moved around the country, first to Tacoma, Washington and then to Philadelphia in 1916.

With a missing father and a working mother, Elliott probably grew up with little parental supervision. At the age of ten, he committed theft and was sent to a reformatory. As he grew older, the thefts became bigger and more frequent. In November 1920, Kate heard that Clarence had been shot in Coeur d’Alene and was in hospital in Spokane, Washington, the big city just the other side of the Idaho-Washington border. Kate left to see Clarence.

A school dropout, Elliott was working at the Baldwin Works in the paymaster’s office. Elliott was asked to distribute salaries while the paymaster took care of other work elsewhere.

As soon as the paymaster left, Elliott left with the money. He went on a spree in NYC and was caught there, trying to board a train to San Francisco. They detectives who interrogated him asked him why he stole the money. He replied “Hey, I never sang in any church choirs. What would you do if $4300 was dropped in your lap?”

Tried in Philadelphia, Elliott expected to be sent back to the Reformatory, but was instead paroled into his father’s custody in January 1921. Elliott found sleepy Coeur d’Alene dull. Within a month of his arrival, he stole from his father and took off. Pursued by the police, Elliott fled to Canada. When he crossed back to Washington State, he was soon captured and sent to the Idaho State Industrial School.

To get out of Industrial School, Elliott joined the Army where he did well and was one of 80 enlisted men nationwide allowed to take the entrance exam for West Point. Elliott turned down this chance. He was discharged from the Army in 1926 and 2 weeks later, with a friend he had made at the School, committed armed robbery. They were pursued and captured, then sentenced to 10 years at the Oregon State Penitentiary.

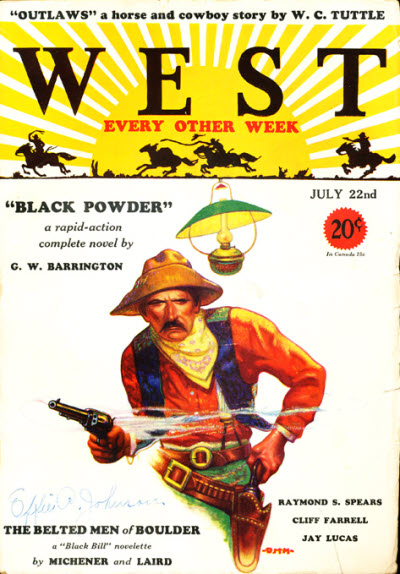

That year, Elliott and his friend from Idaho State Industrial School, Richard Franzen, along with two other inmates, escaped. They scaled a wall using a stolen ladder and then cut through a series of barbed wire fences, only to be recaptured. Despite all the rule violations, Elliott managed to get work in the prison print shop, where he met Jack Laird, in prison for murder. Laird had become editor of the prisoner’s magazine, Lend A Hand. Between 1928 and 1931, Elliot co-authored western stories with fellow inmate Jack Laird. Most of the stories were about an outlaw named Black Bill and were published in the Doubleday pulps: West, Frontier Stories and Short Stories.

Elliott was released from prison in 1933, having spent nearly half his life in institutions. In 1934, Elliott met up with Richard Frandzen and together they setup an counterfeiting operation, printing 20 dollar bills in California. When the Secret Service came calling after four months, Elliott and Richard escaped and met up with Jack Laird (real name John K. Giles), planning to rob mail trains. After pulling a couple of those together, one in 1934 and another in 1935, Laird was captured.

Again running from the law, Elliott and Richard headed towards Minneapolis, robbing a few liquor stores along the way in Montana. In Minneapolis they combined robbery (blank checks from an office safe) with forgery (passing the stolen checks). When caught, they were both sentenced to 35 years at Wisconsin State Prison for forgery. In 1937, the counterfeiting charges from California caught up with them and they were both sentenced to 30 years in Federal Prison (15 years for making the plates and then another 15 for possessing them). Elliott was sent to Leavenworth and Richard to Alcatraz.

In 1941, Elliott was involved in an failed escape attempt that resulted in his transfer to Alcatraz. Early on at Alcatraz, Elliott was assigned to be one of the prison gardeners. Elliott later wrote: “The hillside provided a refuge from disturbances of the prison, the work a release, and it became an obsession. This one thing I would do well.”

From 1946 to 1950, Elliot sued Uncle Sam to get half of his sentence vacated. He argued that it was impossible to make a plate without possessing it so both were one crime, and he couldn’t be sentenced for both 2 consecutively. He finally won his appeal in 1950 and both his and Richard’s sentences were cut to 15 years. Elliott was transferred back to Leavenworth to serve his final 2 years.

Elliott was released in 1952, and Wisconsin did not make him complete his state sentence so at age 46, after nearly three decades in institutions, he was free. Richard was released at around the same time. Both found jobs together and married. In 1955, Elliott moved to El Monte, California (a suburb of Los Angeles) where he worked as a printer. By 1960, Elliott’s old friend, Jack Laird, was also released but only after he had made an almost successful attempt to escape Alcatraz. Together, Elliott and Laird patented a method for training racehorses by exposing them to recorded racetrack sounds.

Today, Escape from Alcatraz is the name of a annual triathlon that starts with a swim from Alcatraz to San Francisco, one of the toughest in the world. A little dangerous, but at least it doesn’t take decades.

This article was based on the research of Bob McNulty, Philadelphia historian (https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia/philadelphia-stories-by-bob-mcnulty-20220420.html)

He has a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/PhiladelphiaStoriesbyBobMcNulty

Fascinating. I have all the West, Frontier, and Short Stories and will have to read a couple of the “Black Bill” stories.

Hope to read your review of the stories