Lon T. Williams followed Robert E. Howard in writing weird westerns. Rather obscure, he was first republished by Larry Estep at pulpgen.com (which has now vanished into the aether). Williams’ stories of deputy sheriff Lee Winters, most of which appeared in Real Western Stories, are formulaic, with the hero encountering weirdness as he returns from successful pursuits of badmen. Or when he goes to the bar. Often starring mythical monsters, they ought to be more gripping than they are.

Though formulaic, occasional flashes of life can be seen, or rather heard in the stories when Williams describes the sounds of the landscape:

Alkali Flat at night was a weird place. Its winds carried noises foreign to its character. Wolves howled there, coyotes barked and yodeled, owls clinked like steel upon musical gongs

King Solomon’s Throne, Real Western Stories, October 1952

There was so much clatter from Cannon Ball’s hoofs that Winters had a momentary illusion of being on a hundred horses. Of course he was merely a victim of echoes. This was, indeed, a place for them, a wilderness of broken walls, gigantic niches, wind-blown towers and stupendous overhanging rocks.

Trail of Painted Rocks, Real Western Stories, February 1956

Here was a region of precipice and cliff. For three or four miles westward, Elkhorn Road was flanked on its northern side by great curving walls of granite; on its southern side, by a narrow, deep gorge. In this gorge, and at this season of chinook winds and melting snows, raced Big Banshee Creek, turbulent and wild, its voice a symphony of hiss and thunder.

The Kite Flier, Real Western Stories, June 1957

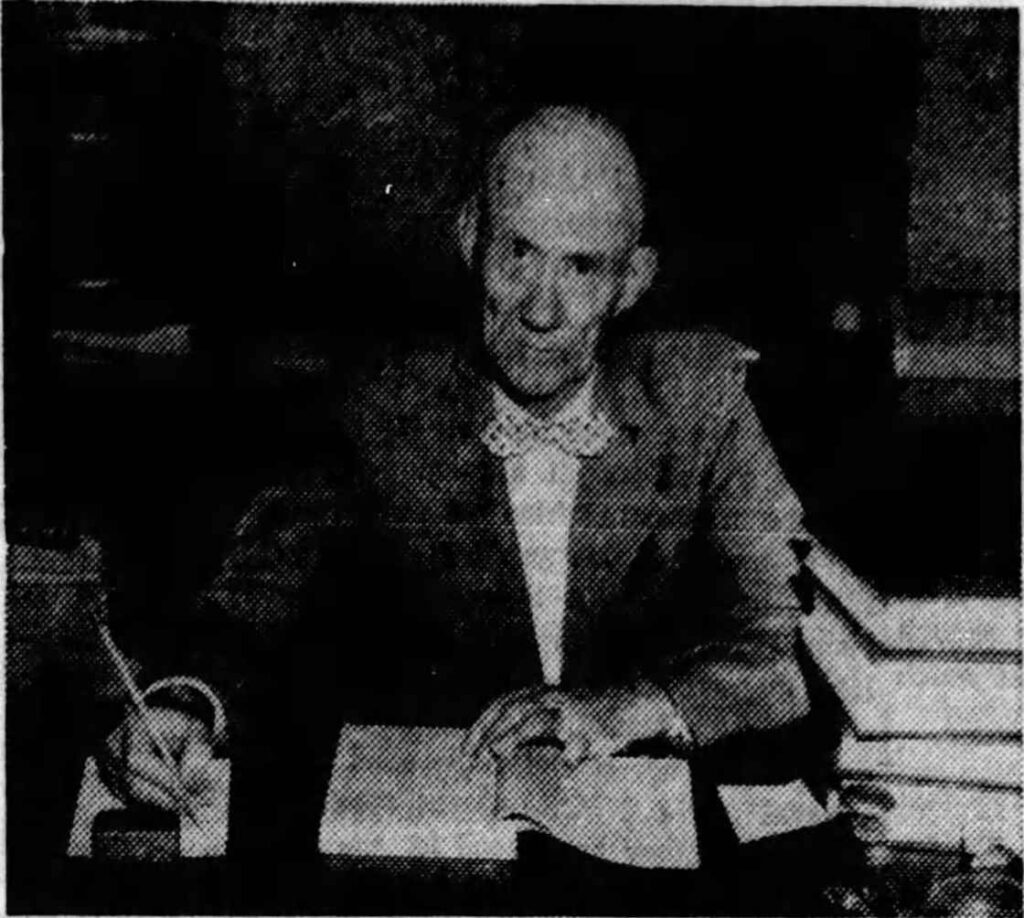

I found Williams himself more interesting than his stories. This profile of him was originally published in the Knoxville News-Sentinel, May 15, 1955.

Basic biographical information:

Lon T. Williams

Lonzo Thomas Williams

27 November 1894 – 11 March 1972

Born in Tennessee, served in the US Army in World War 1, worked as law clerk in Tennessee, moved to Washington state after retirement.

Mild Manners of Federal Judge’s Clerk Hide Author of Violent Old West Tales

THE GENTLE MIEN of a Federal Court law clerk here is deceptive. He has violent thoughts. During the week Lon T. Williams does research on points of law for Federal Judge Robert L. Taylor. On week ends he really breaks loose, writing for Western story magazines.

Mr. Williams began writing fiction as a hobby years ago but couldn’t make any sales until after he read books on short story construction. That was in 1947. The next story he wrote was bought by a Western story magazine and since then, he says, 51 other stories and three short novels he has written have been published. Editors have accepted a backlog of his Western stories that will be appearing from time to time.

Right now there are three Western story magazines on the stands containing Mr. Williams’ fiction. He rates a front cover announcement on each.

PERIOD IS LIMITED

BY TRADITION, he says, a Western-type story must have an American West setting in the period from the Civil War’s end until about 1890.

This man whose fiction heroes stride and ride confidently through the West, sits quietly, day after day, searching in heavy law books.

He came to the law relatively late in life. In 1945 Mr. Williams was graduated from U-T with a law degree and then went to Duke for a master’s in law. U-T Law Dean William Wicker says he believes Mr. Williams was the oldest student, ever to be graduated by the college. After taking the position as the Federal judge’s law clerk, Mr. Williams also taught a course at U-T for five years.

At about the time he was being graduated, Mr. Williams’ twin sons were getting their medical and dentistry degrees. For 11 years before entering his legal career, Mr. Williams had been a title examiner in TVA’s transmission line work. And before that he taught school in the West, though born and reared near Andersonville.

SETTINGS SOUND REAL

BECAUSE OF years he spent in the West, and his reading of Western history, his story settings have an atmosphere that surely must be authentic.

Absorbing atmosphere, Mr. Williams lived on the prairie at Yuma, Col., homesteader country; at Boulder, Col., near ghost mining towns in the mountains; on the Kansas plains, and at Chadron, Neb., just a few miles south of the gold mining town: of Deadwood and Lead in Dakota’s Black Hills.

“If there’s one physical characteristic of the West,” Mr. Williams says, “it’s the wind. I never ceases. The wind adds mystery to the West.” He says he makes use of the wind for atmosphere in his stories.

Another characteristic he found was the lonesome night sound; of the prairies. Night seems lonelier there than here, he says.

CLAIMS HARDY INFLUENCE

ODDLY the writer who has influenced him most has been Thomas Hardy of England’s Victorian period. “Anyone interested in characterization should study Hardy’s Far from the madding crowd,” he believes.

A lot of Mr. Williams’ character types derive from his TVA days, when he traveled in every Tennessee county and into neighboring states. Certain old hand-down sayings and bits of rough philosophy lend themselves to his characterizations. One such saying that Mr. Williams remembers was by a farmer who told him, “Two moves equal a burn-out.”

During the week the law clerk apparently sticks strictly to business. But on the daily bus rides to and from his home near Andersonville he’s thinking out a story plot. Then on the week end he types the story, usually about 5000 words long. He lets it sit for a few weeks to see how it reads after the original enthusiasm of his idea has dissipated, then makes corrections, types a finished draft and mails it.

ABOUT STYLE

Mr. Williams says, “There isn’t much room in Western stories as published nowadays for description. One reason is that editors pay by the word and another is that readers want just the meat without any garnishing.” He uses a great deal of dialogue to carry action in his stories.

Principal characters that reappear in Mr. Williams’ stories are Deputy Marshal Lee Winters and Judge Wardlow Steele. Naturally enough, they seem familiar with the fine points of law. Mr. Williams says he also read books on vigilante courts and gold mining to get background.

Other Western story writers that Mr. Williams admires are Walt Coburn, Ernest Haycox and Luke Short. He says he’s entertained by Zane Grey’s stories, but puts Grey below the others as a craftsman.

REPLIES TO ‘MYTH’

RECENTLY in a “semi-learned” journal an essayist discoursed on the fallacy of Western story writers as a whole. His contention was that the writers themselves have let the myth of the West run away with them. That is, the writers have come to believe that their fictional characters transcended ordinary men; automatically a Western story hero is more courageous and nobler than is humanly possible.

Mr. Williams thinks the myth grew from strong factual background. “The men in the West had to be tough to go and survive.” he says.

Want to read the Lee Winters stories? Some of them are available at the PulpgenArchive site, which continues the tradition of the original Pulpgen.

Here: https://www.pulpgenarchive.com/select_author.php?author_id=554

Thanks for this article, Sai. Western pulps usually don’t interest me all that much but in this case it does. Williams – whom I’d not heard of before now – was my neighbor, more or less, and joins the late “Hascal” Giles as a western pulp writer from East Tennessee, near my own home. I’m always glad to learn of such writers.

Lon Taylor Williams was my grandfather. To me, my sister, and my cousins, he was always Grandpa Lonny. We always enjoyed his western stories and am happy people are still able to read and enjoy them.