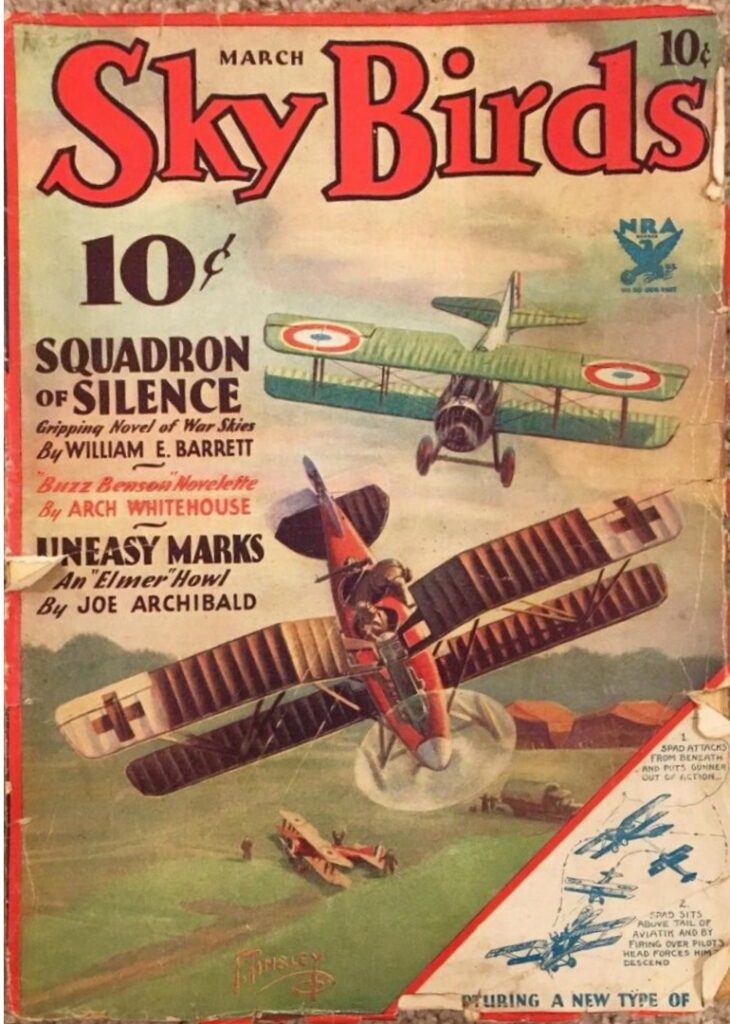

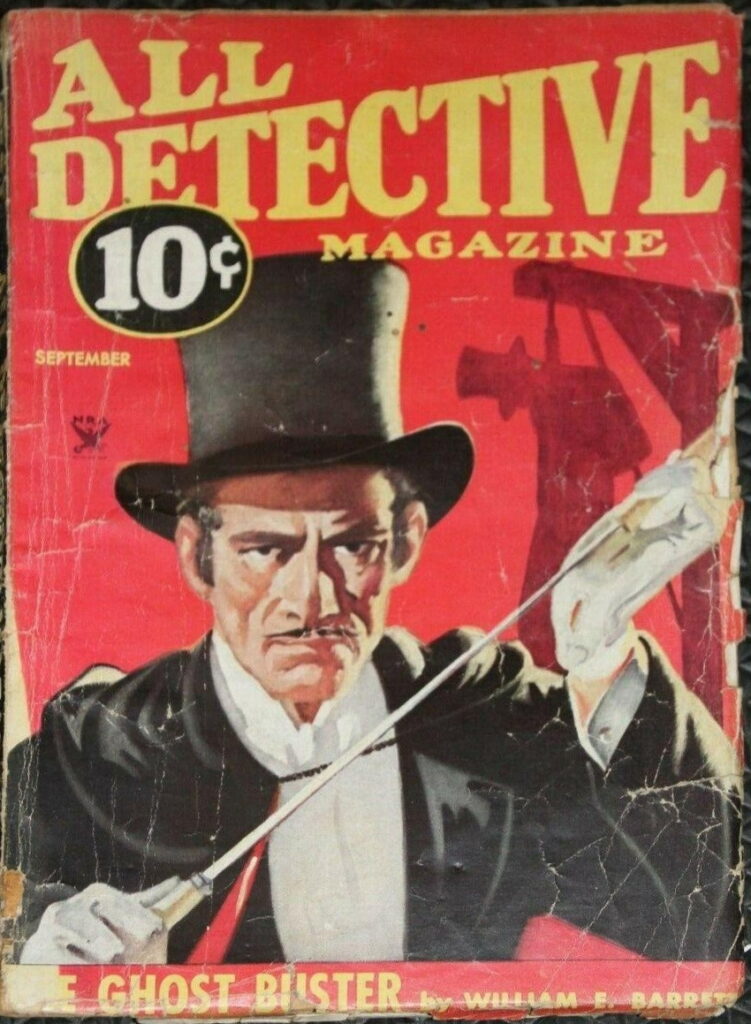

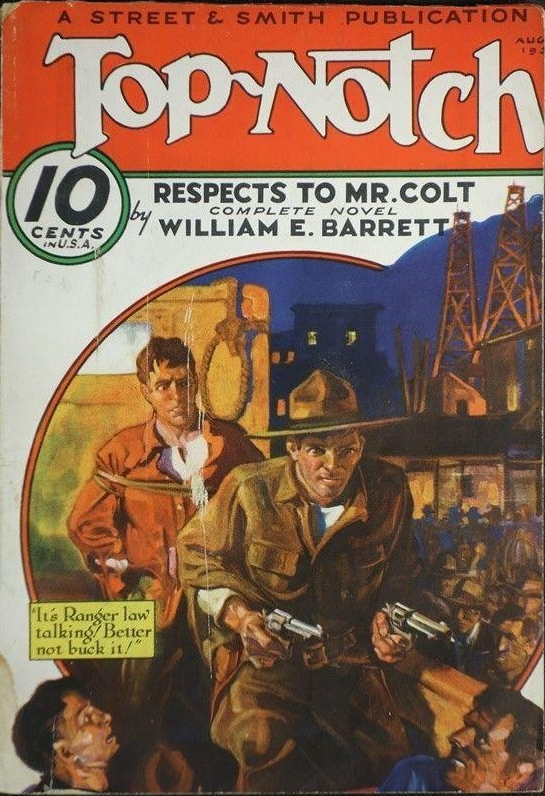

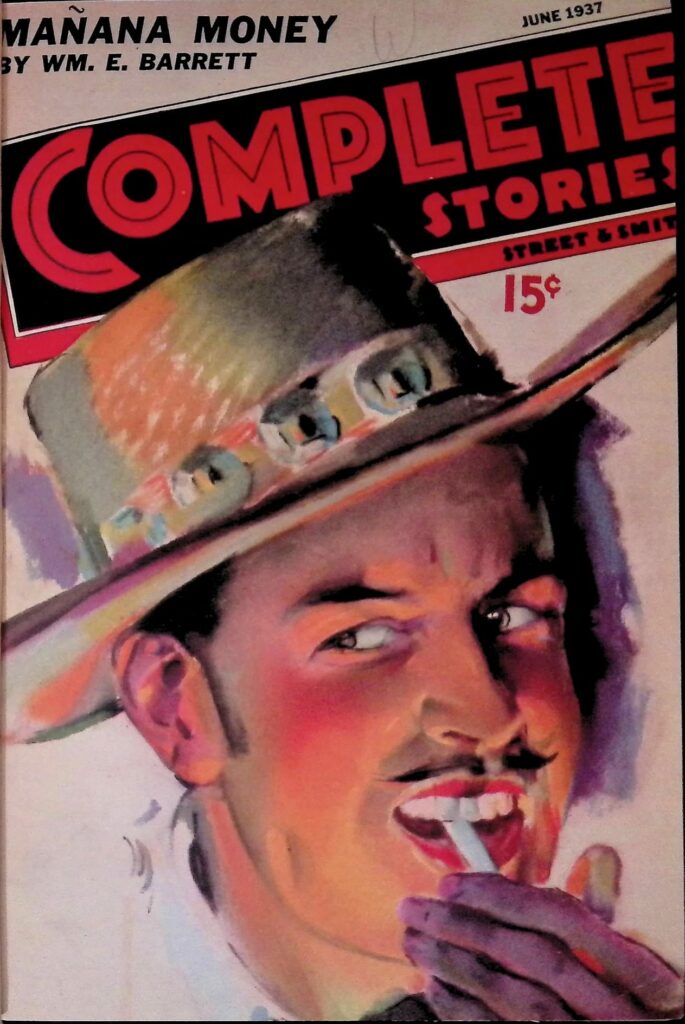

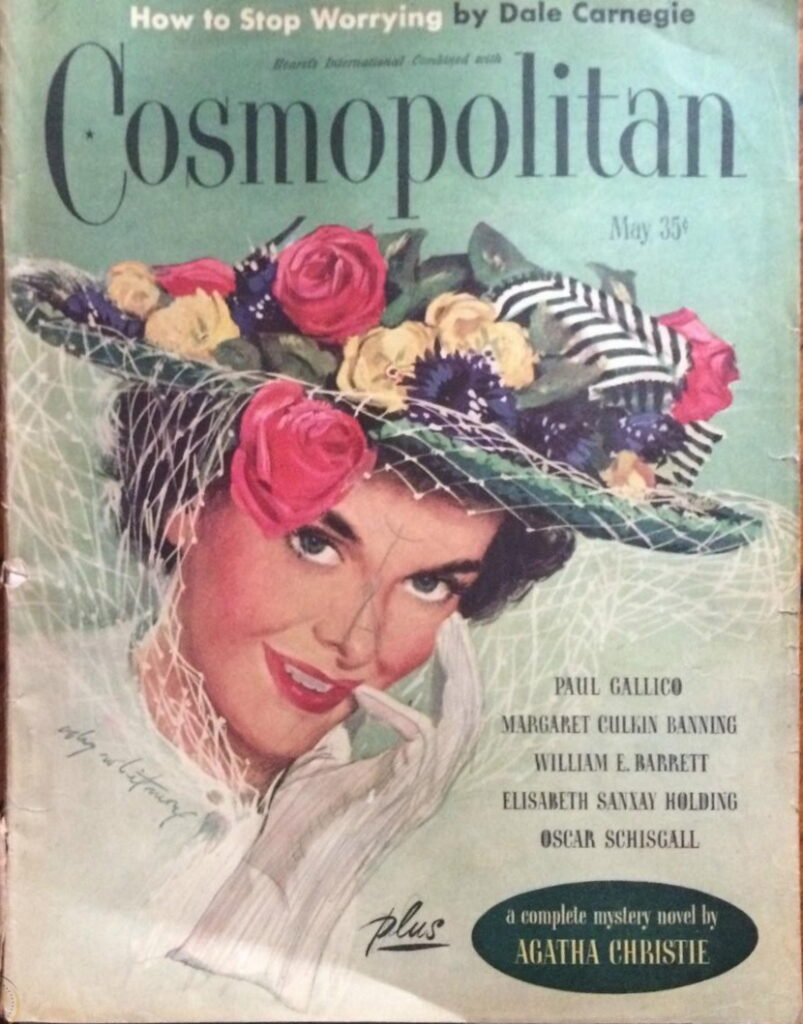

William Edmund Barrett (1900 – 1986) was an American writer, best known for the 1962 novella The Lilies of the Field, later made into a movie that won Sidney Poitier his best actor Oscar. Before Barrett got into movies, he wrote many stories for the pulps, including this one that I reviewed a few years ago. This interview is from that time.

ALMOST a year ago William E. Barrett left a promising position as southwestern advertising manager for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company to write yarns for the pulp paper magazines. To almost anyone—that is, anyone with but a perverted idea of the business—the change might have seemed the most foolhardy thing a young chap could do. It wasn’t. And this is why:

Author Barrett writes and sells on the average of 50,000 words a month. He has a contract with one publishing house to furnish a 35,000-word novel every month for a year, and for each novel he receives approximately $900. With all his contributions to the different paper-backed purveyors of blood and thunder, he nets over $1000 a month. The which is considerably more than twice what his former salary was.

Now consider that author Barrett is just turned thirty, has an apparently inexhaustible fund of fiction adventure in his system and can pour it out with terrific speed over the roller of his typewriter. Then try to figure just how idiotic he was to give up that nice, secure position with the manufacturing house. In the words of any George Ade, he was as foolish as the oft similed fox.

Receives Practically No Rejection Slips

“Pulp paper writing is a whale of a business and plenty of fun,” grins the youthful Barrett, pushing back from the type machine in his office. The office is on the second floor of the Stroh Building, 4541 Delmar boulevard.

“Sometimes one finds persons who sneer at the paper-backed periodicals,” he continued. “Perhaps that’s because they do not have the shadings of character, the finesse of description. But, believe me, they have plenty of action, movement and drama—all stripped down to bone. Also, to my mind it’s the best and surest paying proposition for a writer.

“Tell you what I mean. Suppose you write a story for Harper’s Magazine, send it off and it fails to make the grade. Well, there are possibly one or two other magazines that would even look at your story. The field is limited. A story written for the Saturday Evening Post. I don’t believe would be taken for any other magazine. And a reject from Collier’s would not be suitable for Liberty. But there are any number of magazines in the pulp paper class— distinguished from the slick paper mags—that offer virtually the same market. Some time ago I sold a story that had been sent off thirty-two times.”

Barrett writes regularly for five magazines and has appeared in about twenty-five during the last two years. He sells at a minimum of 2 cents a word and gets sometimes as high as 4 and 6 cents. His average sale price runs 2½ cents. Thera are some monthly and semi-monthly periodicals in which he has appeared without missing an issue for a year. Sometimes he has two or three stories in the same issue. Then he uses several different noms de plume. His stories appear under the names of W. E. Brownestone and Bill Alexander, as well as under his own proper name.

This prolific young writer can do 1000 words an hour. And when he gets done it’s in finished shape for the publishers. He has completed a 35,000-word novel in four days, but usually takes a week or a little longer for that type of story. His short stories he can do in a few days. In addition to his monthly novel he writes three or four short stories a month. And more important, he sells them.

“There are practically no rejection slips now,” he says, “for which, thank the Lord. There was a time when I was not so fortunate. But it seems I’ve got over the shoals.”

Wllilam Barrett is one New York lad who left Gotham for the West when many another youthful bystander was ambitiously heading for Manhattan. His life has been varied enough even if it hasn’t been as full of color as the adventurous, rough and ready careers of his own fiction heroes. But being himself a scribbler, the least concession would be to let him give an account of his biography in his own style.

“I vented my first squawk at life in the City of New York on November 16, 1900.” Barrett began. “I managed to survive the hazards of Manhattan until I was 16, then followed the family star to Colorado. I had prepared at Manhattan College Prep, a Christian Brothers school, for an engineering career, but this proved a misdeal, and I took a whirl at reporting for a Denver daily.

Mathematics Thorn in His Engineering Ambition .

“After about nine months of my cubbing and picture chasing; the city editor of the Rocky Mountain News shook a fatherly head over my newspaper aspirations. And I went to work as general factotem in the office of the Denver Gas and Electric Company, taking an engineering correspondence course and studying at night. You see, ambition was bubbling in my young breast. But ambition was not equaled by my ability at the drafting board. Mathematics was the great thorn in my engineering dream. So after several years I wormed my way into the advertising department of the Westinghouse Company out in Denver.

“My publicity job took me all over the West—mining camps, oil towns, every place where spectacular installations were being made. Later I became publicity manager. And in 1920, the company brought me to St. Louis as southwestern advertising manager, handling a territory that included fourteen states.

“But some base deceiver told me about the big pay and easy hours in fictioneering and I tried my hand. By the time I found out the horrible truth I was too badly bitten by the bug ever to escape, I learned to fly and became a pilot with the idea of writing air stories that would be authentic.

“I was still in Denver when I published my first bit. Yep, a poem in the All-Story Magazine. Then I wrote a story, sent it off and it was accepted. My first one! And it was the worst thing that could have happened. I thought I had the knack of writing by both horns and was in the way of annexing an ace of a racket. However, it was more than a year before I could market another yarn. I got $20 for my first story. My usual income from a short story now—about 6000 words—is $100.

“That first tale was sold eight years ago. Well, I kept pegging away at the work in my spare time until a year and a half before I left my place at Westinghouse I was receiving more from my scrivening sideline than I was from my regular salary. And I was on the road five months of the year, too. So I had to cut loose. I’ve been on my own since last February.

“My total published stuff, if anyone cares, is 263 short stories, 10 complete novels, 13 novelettes of about 12,000 words each and countless articles.

“My wife made her first short story sale a month or so ago, and there was a kick for both of us in that. She has helped me with so many of mine that it was a real thrill to see her push across a yarn of her own. I’ve got a boy 3 years old and a girl 4—to round out the personal narrative. And I’m still in love—”

“Sorry there isn’t more plot or drama or excitement in this—but if there were, this being a sordid age, I’d probably stick a name like Pete Jones on myself and sell the darn thing.”

There you have a pretty fair picture of author Barrett. Except, possibly, for his personal appearance. He is very young looking, with a tract of gray in his hair to make his thirty years teem authentic. He is keen of eye. medium in height and of rather a slight build, despite the fact that his characters are usually of the 6-foot, bulbous-muscled, he-man type.

He specializes in oil field stories, air stories, westerns, air war yarns and general adventure titles. And he has tabooed sex, love and confession stories, largely because he says he hasn’t much of a faculty for them.

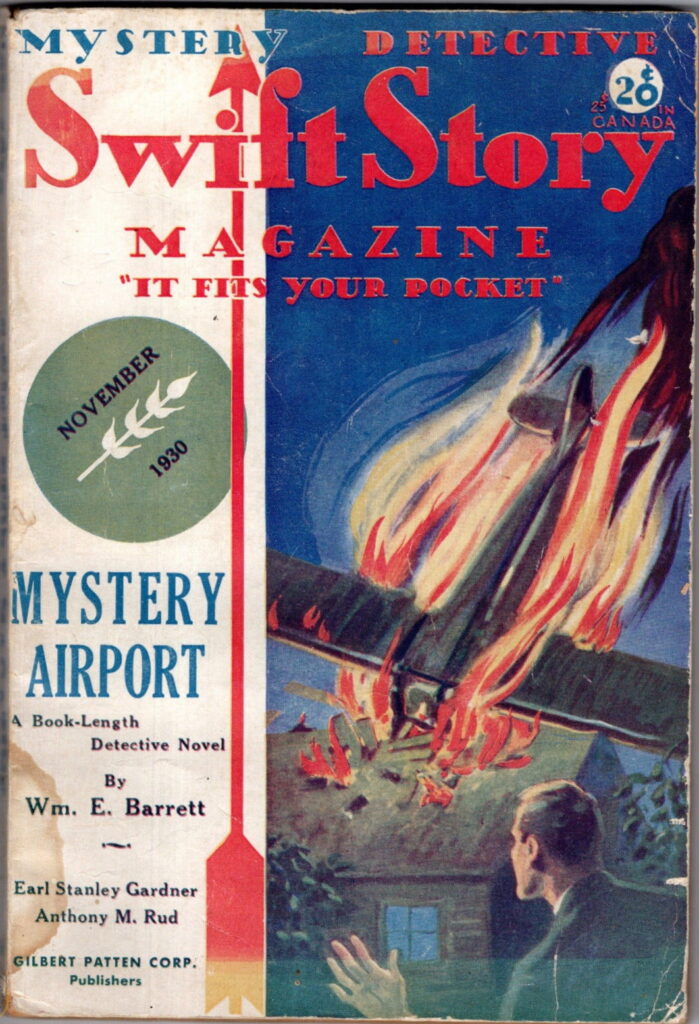

There’s rather a curious story attached to Barrett’s writing for the Gilbert Patten Corporation, publishers. This is the concern which gets out the Swift Story Magazine and which has awarded Barrett the contract for his novel a month.

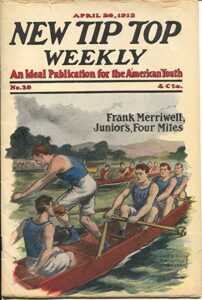

Now the juvenile Will Barrett was as keen a devotee of boy fiction as anyone could find. And the favorite of all the rest for him was the series of Frank Merriwell, the peerless hero of a million adventures. Barrett frankly admits that as a kid he tried his level best to do everything Just like the redoubtable Merriwell. He went in for athletics and got four letters at high school, because that was the way Merriwell would have done.

“I used to feel like kicking myself sometimes,” smiled Barrett, “when I got into a fit of boyish introspection and felt I resembled a butcher’s boy a lot more than the great Frank. Well, sir. I’ve saved every book of the Merriwell series, and every other thing, I believe, that Burt L. Standish ever wrote. Some day I shall give them to my boy to read, because I think they’re classics of their kind.

“Some months ago I received a letter from Gilbert Patten. He told me about several new magazines he was going to publish, and said he had read a number of my stories in other publications and wanted some. That was a thrill, for you know Gilbert Patten, publisher, is the former Burt L Standish, who for two decades poured out the tremendous annals of Frank and later Dick Merriwell.”

So today Barrett is writing stories for the creator of his boyhood’s greatest hero. A sort of passing on the literary torch. Only in this case the torch is fired with an inky ribbon and the imagination of a first-class producer of the clean but lurid dime novel fiction.

Thus far Barrett writes about locales that he knows, places that he has seen. He is an airplane pilot and has a first-hand knowledge of the oil fields and the West. There may, however, come a day when he goes dry on his present topics, when he writes himself out. And with a canny foresight he is preparing against such a contingency.

Not a week goes by, and rarely a day for that matter, when he isn’t studying some new subject. He quotes an old bromide to the effect that if a man concentrates on one study fifteen minutes a day for a year, he will become a fair master of that subject This is what Barrett is doing.

“Now,” he explains, “I’m reading everything I can get my hands on about India. I believe there will come a blow-off down there before many years. Then the fiction buyers are going to want stories about India. And If I’m saturated with the customs, the religion, the character of the country, I believe I shall be able to turn out acceptable stuff.”

Barrett maintains regular office hours, writing from 9 until 5 o’clock daily. The office, by the way, is filled with books, paper and a stack of hundreds of paper-backed magazines. In each of these magazines is some story he has written. He will soon have out a book of a semitechnical nature on his study of airplanes, particularly of the old war-time machines.

Usually he works just during his office hours. But if a story “gets hot,” he will sit there at his typewriter until midnight or later, hammering away as fast as his fingers will fly. And his wife’s dinner or bridge party or show has to do without him. Mrs. Barrett has become rather accustomed to this, however. and understands. He has written steadily for as long as eighteen hours at a stretch.

Does he read? Voluminously, but not fiction. He quit reading fiction when he became a professional producer.

“My business now,” he says, with his frequent grin, “is to write yarns, not read ’em. After all, there’s more money in that.”

[This interview originally appeared in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Oct 26, 1930.]

Recently William Barrett’s pulp file copies were offered for sale. He had them bound and they looked to be in fine condition but most collectors steer clear of bound pulps so the complete collection did not sell. I believe the price was $12,000.

They then were offered at lower prices for individual bound volumes and most were sold. My favorite Barrett stories were his Needle Mike series in Dime Detective and his work for Shaw’s Black Mask.

I saw those copies; they were highly trimmed. Otherwise fine. Would have liked to snag a few but the ones I wanted went faster than i could draw my trusty credit card from its holster.

I got a couple of those Barrett bound volumes. Exceptionally nice condition other than the trimming.

just received a copy of The First War Planes handed down to me through my faher in law. given to him by his father who served with the R.A.F.